EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the final part of a three-part series on LGBTQ history in the Lehigh Valley, during Pride Month. (See Part 1, Part 2)

ALLENTOWN, Pa. — Allentown passed an anti-discrimination ordinance in the 1960s that protected people from discrimination based on age, race and sex in employment, housing and the use of public facilities.

But the ordinance didn't protect people from discrimination based on gender identity or sexual orientation.

- Allentown's anti-discrimination ordinance did not include gender or sexual orientation when it was first created

- Activists tried to amend it three separate times since its initial adoption

- The Lehigh Valley LGBT Community Archive is now looking for more materials, especially from LGBTQ people of color and trans people

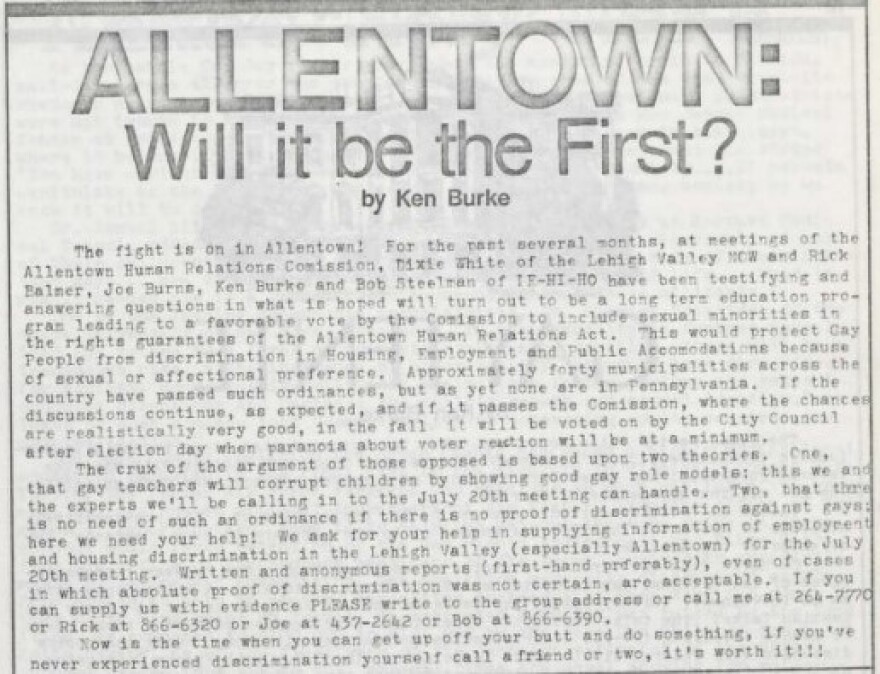

Activists tried multiple times in the 1970s and '80s to change the ordinance to include LGBTQ people, but their efforts were unsuccessful.

But when head of the Allentown Human Relations Commission Felix Molina went to local activists Liz Bradbury and Patricia Sullivan in 1998 and asked them to try to change it, they tried a new technique — electing new city council members.

There are not many photos from that time in Lehigh Valley LGBT Community Archive, which is owned by the Bradbury-Sullivan LGBT Community Center and kept at Muhlenberg College’s Trexler Library.

That's because Bradbury stored them on hard drives that she can no longer access.

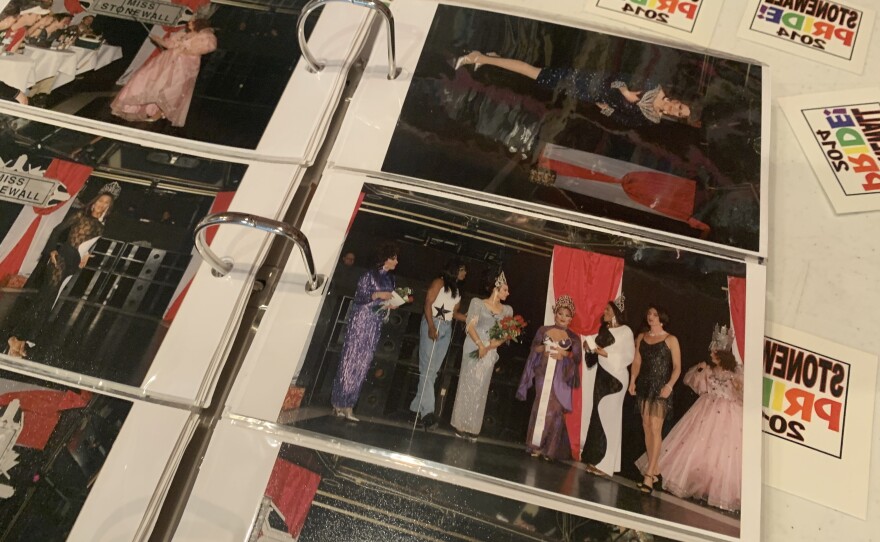

The archive contains photographs, handwritten notes, organizational records, newsletters and more related to LGBTQ people’s lives in the region.

The photos are just one example of what is missing from the archives — prompting a new push from the archivists to gather more materials as Pride month comes to a conclusion.

Early efforts to amend anti-discrimination ordinance

In 1977, several local organizations, including Le-Hi-Ho, came together to form a group dedicated to changing the ordinance.

The group was called Citizens Concerned for a Better Community or CCBC, and it advocated to change the ordinance to include “sexual and affectional preference.”

Its efforts were supported by the city’s Human Relations Commission.

The city council president not only refused; he also tried and failed to issue a gag rule preventing public commentary on the issue, according to an exhibition made from the archives.

Activists protested by showing up to city council meetings with duct tape over their mouths.

Bob Wittman, a member of Le-Hi-Ho, said people also set up a door frame on the Lehigh County Courthouse Plaza and walked through it, demonstrating they were “coming out of the closet.”

In 1979, a court ruled that the city government could not change the law, which ended that effort, according to the exhibition.

Activists tried again to amend the ordinance in 1985, this time to include people with AIDS, but the effort once again failed.

The third attempt

Bradbury and Sullivan worked with Molina to try to persuade the members of the Allentown City Council at the time to change the ordinance.

But only one was willing to put it up for discussion, and they needed two votes to put it on the agenda, Bradbury said.

Bradbury said some people thought she should not be advocating to include gender identity in the ordinance because the amendment could be easier to pass without it.

But Bradbury said she felt it was important to include both gender identity and sexual orientation because part of anti-gay discrimination relates to gender presentation. She said she also did not feel it was right to leave trans people out of the amendment.

“You can’t leave out part of this community," Bradbury said. "It’s wrong to do that."

After the first attempt, Bradbury and Sullivan started to work to get their own candidates on council.

“I was like, ‘Well, why don't you do it?’”Former city councilwoman Gail Hoover

Bradbury decided to ask local real estate agent Gail Hoover if she would run because Hoover was open in her sexuality, had flexible hours in her job and was good at public speaking.

Hoover had not been very involved in politics before Bradbury asked her to run.

“I was like, ‘Well, why don't you do it?’” Hoover said, laughing.

But Hoover said she knew they needed someone with a “wide appeal” who was not singularly focused on LGBTQ activism.

“From my job, there was name recognition to begin with,” Hoover said. “And most people knew that I was gay, but I'm not, like, militant about it. I'm like, ‘Yeah, I'm gay.’ And if you want to talk about it, we can talk about it, but I don’t feel the need to.”

MORE ON THE SERIES:

Part 1 — Seeds of Valley's LGBTQ history planted even before Stonewall rebellion

Part 2 — What the LGBTQ Community Archive has to say about the Lehigh Valley's response to the HIV/AIDS crisis

Bradbury and Sullivan were running the Lehigh Valley chapter of the Pennsylvania Gay and Lesbian Alliance for Political Action, or PA GALA, at the time. PA GALA was an organization that aimed at getting LGBTQ people and allies involved in politics, run by lawyer and activist Steve Black.

PA GALA had a mailing list of many local LGBTQ people and allies. The organization interviewed candidates about their positions on LGBTQ issues and sent out voter guides for every local election.

Bradbury and Sullivan used that group of voters to help Hoover and another candidate who supported the change to the ordinance, Julio Guridy, win in the Democratic primary race and ultimately the election.

Guridy was one of the first Latino people on Allentown City Council. He served on the council for 20 years.

A few months after Hoover and Guridy were sworn in, Allentown City Council voted 5-2 to amend the ordinance.

The mayor at the time, Roy Afflerbach, later signed the bill into law.

“There was hugging and tears," Hoover said. "It was a great celebration in the room."

Ballot petition

But the group couldn’t celebrate for long, Bradbury said.

An opposition group called Citizens for Traditional Family Values soon filed a petition to add a question to the ballot about whether the amendment to the anti-discrimination ordinance should stand.

Bradbury said it would have been “devastating” if the question had gotten on the ballot. Even if the majority voted to keep the ordinance amendment, LGBTQ people in the area would be able to see how many people voted against it.

“It's very uncomfortable to be in a town where you know that that many people would vote to take away your employment and housing and public accommodation,” Bradbury said.

So Bradbury, Sullivan and many other volunteers started working to verify the signatures on the petition.

The group soon realized that some members of Citizens for Traditional Family Values had lied to some of the signatories about what the petition was for, and that many of them might have been willing to take their name off the petition.

Bradbury said she and Sullivan ran the operation out of their house in Allentown. Volunteers were in and out of their house from 7 a.m. to midnight, finding signatories’ numbers, putting them on a spreadsheet and calling them up to see if they actually wanted to be on the petition.

Many people said the opposition group lied to them about what the petition was about, according to Bradbury, and agreed to sign a form that would remove their name from it.

But some knew what they had signed, she said.

“A lot of people would call and the person would be like, ‘No, I hate those people, they shouldn't have rights,'" Bradbury said. "That was very hard to hear."

"So we determined that if it was an LGBT person that was calling people, and they got three of those calls in a row, they had to leave. It was too devastating.”

Ultimately, the opposition group lost a lawsuit against the amendment, and Bradbury sued it for lying to people about the petition. Bradbury said the opposition's law firm was not willing to represent them in the case.

“Their law firm was saying to them, ‘Well, if you misrepresented yourself, I can't defend you,’” Bradbury said. “So they were going to lose, and it was going to be really serious. I could have sued them for millions of dollars, potentially.”

Bradbury told members of Citizens for Traditional Family Values that she would drop the lawsuit if they promised to never try to overturn it again.

The group agreed.

Lessons for activism today

LGBTQ activism is not a thing of the past.

Many people today are fighting against anti-trans legislation across the country and efforts to limit what is taught about LGBTQ people in schools.

Hoover said when she was trying to change the anti-discrimination ordinance, the way she got people to change their minds was by speaking from her heart.

“When you speak from your heart, people can relate to you,” Hoover said. “And once someone has related to you, it's a lot easier to get them to kind of see the world the way you're seeing it. Then that changes people's perspectives.”

Bradbury said she thinks the single most important thing activists need to do is put together clear and concise pieces of educational information to refute opposition arguments.

Bradbury did that when Citizens for Traditional Family Values started to make false claims about the effect of the ordinance amendment.

“Nobody ever got hurt from it," Bradbury said. "No employer ever got in trouble from it. It didn't make people change their entire lives. It didn't hurt people's religion. None of those things happened."

"If you're inclined to say, ‘Oh, this is too hard to do, oh, this is too complicated, nobody's listening to me’ — no person who was fighting for civil rights ever let that stop them.”Local LGBTQ activist Liz Bradbury

Bradbury also said activists have to be prepared for the work to be difficult.

“As an activist, you have to recognize that this stuff is hard, and some of it's hurtful," she said. "And you have to prepare for that.

“Because if you're inclined to say, ‘Oh, this is too hard to do, oh, this is too complicated, nobody's listening to me’ — no person who was fighting for civil rights ever let that stop them.”

Finding more for the archives

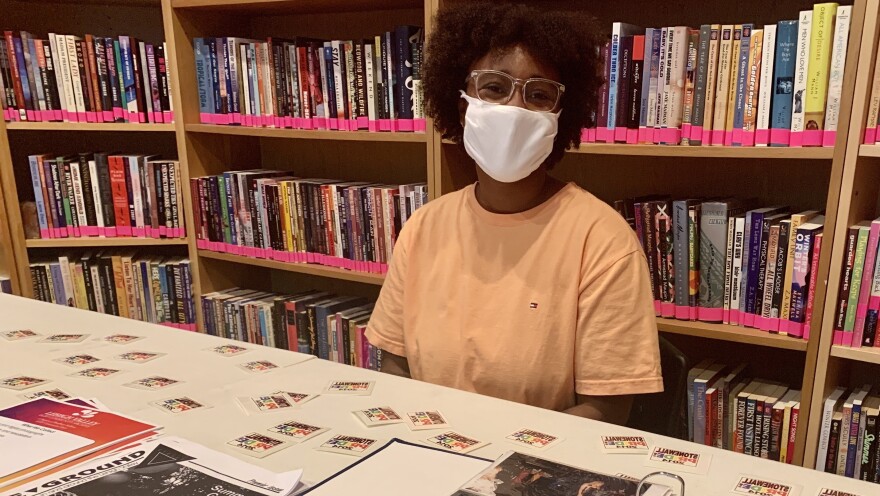

Susan Falciani Maldonado, special collections & archives librarian at Muhlenberg College, said she and archivist Tiersa Curry are mostly caught up in cataloging and digitizing the archival material.

So they are now looking for more content from community members.

Falciani Maldonado said the archives is looking for anything related to the history of LGBTQ people in the Lehigh Valley — regardless of the format.

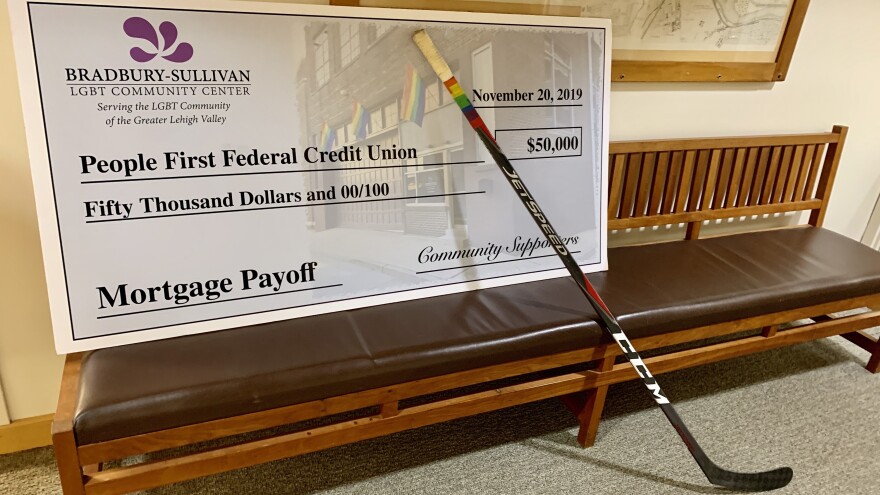

“We have a hockey stick back there,” Falciani Maldonado said. “We have six-foot checks. We have signage that used to hang in the park where they dedicated trees to folks who passed away from AIDS.”

In particular, the archives are looking for information about the life of LGBTQ people of color and trans people in the earlier days of LGBTQ activism in the region.

“We're really looking for anything, but we're trying to start focusing on gender non-conforming and BIPOC voices so that the archives can be more inclusive and accessible for people that are a part of those communities,” Curry said.

Currently, the archives have one oral history from a trans community member from that time — Sandy Mesics, who was born in Bethlehem in 1952.

But Mesics moved to Philadelphia after graduating from college in the 1970s, and didn't begin her transition until then.

“This would have not flown in the Lehigh Valley at that time,” Mesics said.

There also are not many oral histories from LGBTQ people of color who were in the Lehigh Valley before the turn of the century.

One is from Felix Molina, the head of the Allentown Human Relations Commission who asked Bradbury and Sullivan to help pass the ordinance amendment. He moved to Bethlehem in the 1990s, and he said he felt respected in the community when he lived there.

“Everywhere I made myself respected, and everyone knew that I was gay,” Molina said in his native Spanish.

Curry and Falciani Maldonado now are looking to form an advisory committee to help guide where they look for new materials, and they hope to make the committee as diverse as possible.

Falciani Maldonado also hopes the committee will work to help build trust with community members about contributing to the archives, which she said sometimes is difficult.

“A lot of this material, obviously, it's deeply personal, and the discrimination that has happened, and continues to happen, does not encourage trust in organizations,” Falciani Maldonado said.

Curry said seeing the materials in the archives, especially materials from other LGBTQ people of color, inspires her.

“They were breaking barriers without having the thought that these things are groundbreaking,” Curry said.

“It makes me think, how can I facilitate that in the present moment — making spaces for me and others, just like they did in the past?”

To submit potential archival material, email Curry at tiersa@bradburysullivancenter.org.

Correction: An earlier version of the article misidentified the second council member Bradbury and Sullivan helped get elected. It was Julio Guridy.