BETHLEHEM, Pa. -- The Bethlehem Police Department is working to revamp and expand its surveillance capabilities throughout the city.

Bethlehem received $200,000 from the Gun Violence Investigation and Prosecution Grant Program in February, which the police department plans to use to expand its surveillance network in the next six months, according to Police Chief Michelle Kott.

- Bethlehem has received $302,000 from two grants in order to overhaul its surveillance network

- Police Chief Michelle Kott hopes that cameras, along with other interventions, will help deter and solve crime

- Experts warn that it may not be so simple

Kott also said the department received a $102,000 grant through Sen. Lisa Boscola’s office that helped police update their surveillance network.

“Our city camera system was very archaic,” Kott said. “And there were cameras that needed to be replaced, because they were no longer functional due to their age, or we needed to add in certain sections of the city where we have festivals and events, just for infrastructure purposes.

“So the majority of the cameras that we've added within the last year have been in the Main Street area, down to Sand Island. Think about the area that primarily is heavily utilized for Musikfest, Celtic Fest, and shopping for the Christmas season."

Eric L. Piza, professor of criminology and criminal justice and director of crime analysis initiatives at Northeastern University, warns against thinking of areas of crime too broadly when it comes to surveillance.

Crime exists in “micro places,” so often police departments define high-crime areas too broadly by pointing to a whole street or neighborhood, said Piza. Cameras are also limited by how much they can capture in a field of vision.

A layered approach

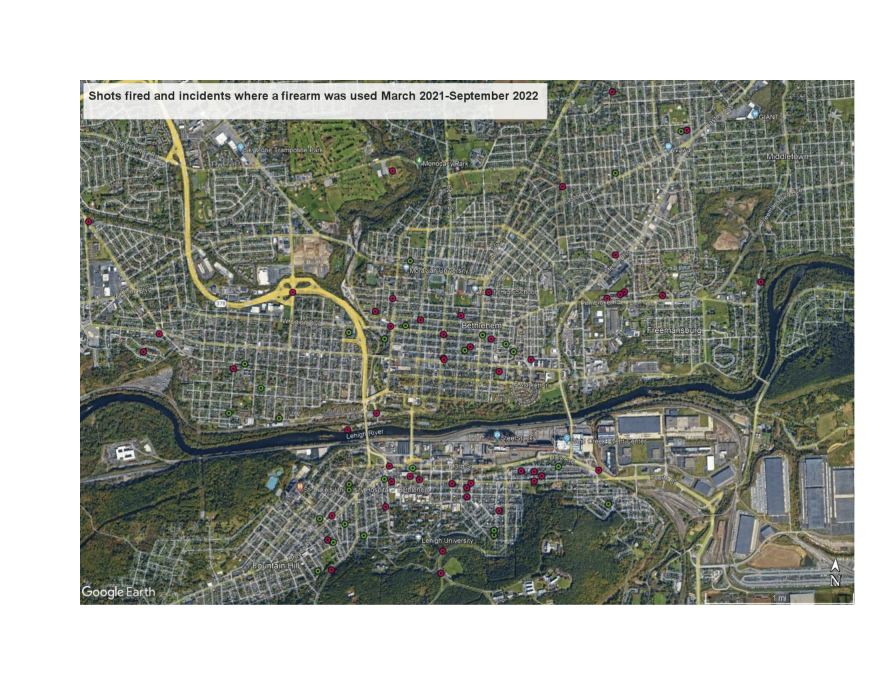

Kott pointed to a map to show where gun crime had been reported and where cameras are likely to go. When it was brought up that many of those areas are far from one another and that there doesn't seem to be a concentrated place where gun crime is committed, Kott replied, “Honestly, when I'm looking at the map, I don't want to just do one side of the city, I really feel like you have to spread it out.

“And with the spread being, you know, as large as it is, you have to concentrate on thoroughfares throughout the city… So, if there isn't a specific area that is surrounded with red dots, or green dots, those are some of the locations that we're going to focus on. Because it's hopefully going to catch the, you know, the egress of somebody.”

"If individuals believe that they're going to be readily identified and caught because of technology that we have, hopefully, they will not commit crimes here in the city," Kott said in an earlier interview. "But if they do commit crimes, that technology will help us readily identify that individual and successfully prosecute them."

Piza said cameras are not an effective intervention on their own. For example, passive monitoring is not as effective as active monitoring. Increased lighting also makes cameras a more effective intervention, he said.

“You are going to be disappointed if you expect criminals to see cameras and be deterred,” said Piza. “Other interventions need to be in place.”

When asked about this kind of multifaceted approach, Kott said: “You cannot put a price tag on the value of having a good relationship with your community members, because they're the folks that are going to reach out to you when a crime occurs. They're the folks that are going to provide you with information, when you do get a still image of someone, and you need to identify them, that comes from your community.”

When lights specifically were mentioned as an effective intervention, Kott said, “Primarily on the South Side, there are a number of lights that are burned out. And we're really actively trying to work with our public works people to have them get out there and repair that lighting. Because I agree that environmental factor definitely helps deter people from committing crimes.”

Training in technology

Nicol Turner Lee, a senior fellow in governance studies at the Brookings Institution and the director of its Center for Technology Innovation, studies artificial intelligence and other technology that police may use to predict or track crime.

“Law enforcement is not new to this in their use of surveillance and other technologies, Turner Lee said. “From drone surveillance, predictive analytics, thermal heat maps, and now cameras, law enforcement across the country have been using these tools. The challenge, however, is related to training police officers on equitable use of these technologies…

“In the deployment of technologies among law enforcement, there's always a slippery slope, one that is focused on public safety, but that can have consequences for communities that tend to be over-policed and over-surveilled.”

"Yeah, historically, surveillance has been shown to contribute to inequities. However, in this community, we want to use the data and the resource of video footage to decrease inequities and to increase equity through access.”Hasshan Batts, executive director of Promise Neighborhoods Lehigh Valley

Turner Lee’s primary suggestions were guardrails on the use of the technology as well as transparency and evaluation of the impact of the tools.

As for the types of guardrails that should be in place, Turner Lee said those should largely be determined by the community.

Hasshan Batts, the executive director of Promise Neighborhoods Lehigh Valley, hopes that the data recorded can be open to the public.

“I would hope that the community controls the information, because I don't even like the word 'surveillance' right," Batts said. "Data video footage has been shown to expose corruption, oppression, and assaults within communities.

"Yeah, historically, surveillance has been shown to contribute to inequities. However, in this community, we want to use the data and the resource of video footage to decrease inequities and to increase equity through access.”

Kott said that wouldn’t be possible in cases where there is an open investigation, as the footage would be evidence. She did say that so long as there isn’t an open investigation, citizens are able to request footage through a Right-to-Know request with the city, as they often do for car accidents to see who was at fault.

At the end of the day, says Turner Lee, surveillance technologies can lend an impression of ease to those working to solve crimes.

“But computers and software are no substitute to the type of relationship building, and community engagement, that still needs to happen to avert high rates of gun violence,” she said.