GERMANSVILLE, Pa. — There’s usually one day during the annual Bake Oven Knob raptor count when thousands of migrating birds of prey fly through the Lehigh Valley, Chad Schwartz said.

“This year, it looks like Sept. 22,” said Schwartz, executive director of the Lehigh Gap Nature Center. “We had 3,200 birds in one day.

“Not the majority for the season, but it made up a pretty good portion of the season’s totals.”

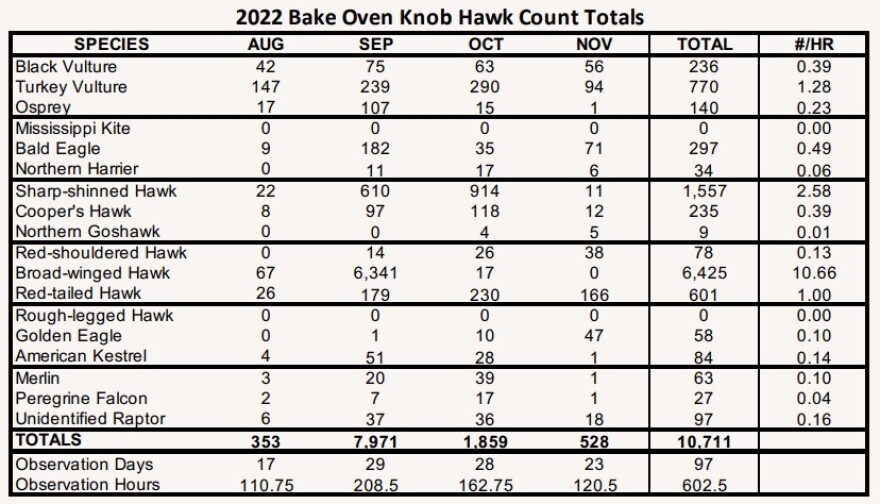

Almost 11,000 birds of prey were counted this year during the Lehigh Gap Nature Center’s annual autumn hawk watch as they made their way along the raptor "superhighway" in the Valley’s backyard. While officials are still reviewing data collected during the season, which ran from Aug. 15 to Nov. 24, Schwartz said numbers generally fall in line with recent trends, showing some species are more robust than others.

Broad-winged hawks, which are compact birds with wings that come to a distinct point, made up more than 6,400 of the count, Schwartz said.

"You have to be in the right spot at the right time, especially for broad-winged hawks, because they're a little more unpredictable as far as where they fly."Chad Schwartz, executive director of the Lehigh Gap Nature Center

“We always know, or we always at least hope, that we're going to get a really good count of those birds, but these days, those birds sometimes will fly off the ridge,” he said. “ … It really all depends on the winds and how they're flying on a particular day.

“It's all in the same ridge, but it's just you have to be lucky. You have to be in the right spot at the right time, especially for broad-winged hawks, because they're a little more unpredictable as far as where they fly.”

Conservation research

For more than 60 years, volunteers and conservationists have stood at the high point on the Blue Mountain ridge of the Appalachian Mountains each fall, recording birds of prey for the nature center’s annual hawk count.

Started in 1961 by Donald S. Heintzelman, the Bake Oven Knob hawk count was a response to the state-approved slaughter of birds of prey, which were viewed as a threat to poultry and other game animals, that decimated raptor populations.

While state and federal laws have since been passed to protect some species, the count has continued annually as other threats, like habitat loss to development, increase.

A 2021 analysis from the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and BirdLife International found that 30% of 557 raptor species worldwide are considered near threatened, vulnerable or endangered or critically endangered, the Associated Press reported. Eighteen species are critically endangered, including the Philippine eagle, the hooded vulture and the Annobon scops owl, the researchers found.

Of threatened birds of prey that are active mostly during the day — including most hawks, eagles and vultures — 54% were falling in population, the study found. The same was true for 47% of threatened nocturnal raptors, such as owls.

To help international conservation efforts, data from the LGNC’s count is reported to the Hawk Migration Association of North America. Those scientists look at population and migration trends and patterns, keeping an eye out for declines.

However, even though local counters might see less of one species in any given year, it doesn't necessarily indicate a widespread decline, Schwartz said. It could be that behaviors are changing.

“Some birds might not migrate because it stays warmer up north now. Some birds are able to use off-ridge winds to migrate,” he said. “There are other factors that could be at play, but sometimes, these numbers that we're seeing do represent declines.”

By combining data with other hawk watches, scientists can get a wider view on raptor populations to see overarching trends or patterns.

“It's nice to know that our little hawk watch here, at Bake Oven Knob, hopefully will support larger-scale research.”Chad Schwartz, executive director of the Lehigh Gap Nature Center

“Our data becomes part of a much larger database, which includes data from dozens of hawk watches — actually hundreds of hawk watches — across the Americas,” Schwartz said. “It's pretty cool to have information that then goes into a larger database for scientists to use.

“It's nice to know that our little hawk watch here, at Bake Oven Knob, hopefully will support larger-scale research.”

‘Over 300 hours’

It was a slightly rainier season than previous years, Schwartz said, but volunteers and center staff were able to put in hundreds of hours at the North Lookout of Bake Oven Knob, scanning the skies for migrating raptor.

“We had somebody up there just about every day,” he said. “There were a few days where it was foggy or rainy and we couldn't count, but compared to other years we did really well.

“We have over 300 hours up on the hawk watch this year.”

Notably, a counter spotted a rough-legged hawk, an arctic raptor that hasn’t been seen in the region since 2012. There were also 367 bald eagles counted this year.

“That's within the top 10 highest counts,” Schwartz said of the eagles. “That's a species that represents a conservation success story. They’ve really, really come back, and each year we've seen pretty strong numbers for bald eagles.”

However, not all birds of prey are faring as well. While more kestrels and northern harriers were counted this season, their population numbers are still concerning.

“Kestrels are a grassland- and farmland-dependent species, so habitat loss has really been impacting them,” he said. “Also, there's a bird called the northern harrier — it's the same story. They're a grassland bird. So, we've been seeing declines in those species.

“ ... We had more kestrels this year than we had last year, which is good, but the numbers are still below long term averages for kestrels. Still not great — better than last year — but still not a great total.

"Harriers — same thing.”

Populations of kestrels, also called sparrow hawks, have been declining for years, with researchers pointing to habitat loss and pesticide use as contributing factors. In June, the wildlife habitat team at WM Grand Central Environmental Education Center banded five kestrel chicks as part of conservation efforts.

So far, it appears the LGNC’s overall count falls in line with recent trends, in both increases and decreases, Schwartz said.

“We did see more birds than last year,” he said. “I'd say this year was definitely an improvement in numbers over 2022, but otherwise, things are pretty much within recent trends.”