BETHLEHEM, Pa. — When flocks of thousands of healthy snow geese glide over the Lehigh Valley’s rooftops, their honking and wing-flapping almost sounds like a carefully choreographed performance as they migrate through the region.

When they’re infected with HPAI, or highly pathogenic avian influenza, commonly referred to as bird flu or H5N1, snow geese start acting strangely — the complete opposite of the grace they display in flight.

“It’s very neurological,” said Kat Schuster, a licensed wildlife rehabilitator and lead clinic manager at Pocono Wildlife Rehabilitation & Education Center.

“It affects them where they're basically head shaking, head bobbing, disoriented.

“Once they get to that stage of the disease, they can't fly, and they literally just fall out to the ground. At the end of that is they're throwing up blood. That's the last stage.”

Bird flu has landed in the Lehigh Valley, contributing to the deaths of about 5,000 migrating snow geese in both Lehigh and Northampton counties.

Highly contagious

Highly contagious in wild and domestic birds, the infected can only be euthanized to quell the spread of the disease. And the United States this month saw its first human death attributed to bird flu.

“The birds that were flying over my house yesterday and the day before, the snow geese, I'm just thinking, 'What is their fate? Are they next?' I don't know."Chrysan Cronin, director and associate professor emerita of public health at Muhlenberg College.

While federal officials say the risk to people is low, local experts said it’s important for residents to stay informed, as well as to protect themselves and their pets through proper hygiene practices and keep a wide berth around infected animals.

Residents also might feel the affects of the disease in their wallets, as the price of eggs continues to climb.

“The snow geese have been flying over," Chrysan Cronin, director and associate professor emerita of public health at Muhlenberg College, said.

"They're so beautiful — hundreds and hundreds of them are still flying over my house every day.

"The birds that were flying over my house yesterday and the day before, the snow geese, I'm just thinking, 'What is their fate? Are they next?' I don't know.

“It’s just so sad that we're seeing this happen to all kinds of species now, not just wild birds, but now with our cattle in the United States, it's just going through herds. It's alarming — cats, dogs.”

Bird flu in the Lehigh Valley, beyond

HPAI, commonly referred to as bird flu, is caused by an influenza type A virus, and is highly contagious and often fatal in birds.

While some wild bird species can carry the virus without becoming sick, HPAI has been affecting both wild waterfowl as well as domestic poultry species since 2022.

Although the threat to humans is low, local health officials said it’s important to keep a close watch on the situation before it turns into a pandemic.

The virus jumped from birds to mammals in the Lehigh Valley in May 2023, when a red fox became the first mammal in the region infected.

In early May last year, a bald eagle collected on March 11 in Northampton County also tested positive.

In November, state agriculture officials mandated Pennsylvania dairies to bulk test for avian influenza. While no cases of the virus have been reported in Pennsylvania cattle, other states have seen a marked uptick in cases since the first outbreak in cattle was reported in March of last year.

“On April 1, CDC confirmed one human HPAI A(H5N1) infection in a person with exposure to dairy cows in Texas that were presumed to be infected with the virus,” according to the CDC.

“This is thought to be the first instance of likely mammal to human spread of HPAI A(H5N1) virus.”

So far, 16 states have seen bird flu outbreaks in cattle, with 928 dairy herds affected, according to CDC data.

This month, state Game Commission officials said about 200 snow geese were found dead in Lower Nazareth Township and Upper Macungie Township from suspected bird flu.

Less than a week later, the Lehigh Valley Zoo announced the barnyard birds, waterfowl and penguins were taken off exhibit due to concerns about the virus.

However, the snow geese situation has only worsened.

By the end of last week, the Game Commission said 5,000 snow geese had been impacted at two Lehigh Valley sites.

“Because these two sites are at the epicenter of resurgence of HPAI in Pennsylvania, the Game Commission opted to depopulate birds remaining at the sites and hired a contractor to retrieve and properly dispose of them, as well as any dead birds that were already there,” said Travis Lau, communications director with the state Game Commission.

Officials began euthanizing ill birds Monday and Tuesday at the Northampton County and Lehigh County sites, respectively. The birds were shot with non-lead ammunition.

“At the Northampton site, there were many more dead birds there than initially reported.”Travis Lau, communications director with the state Game Commission

“At the Northampton site, there were many more dead birds there than initially reported,” Lau said.

“At the conclusion of the cleanup, total mortality was estimated at 5,000 birds, about 450 of which were shot in addition to the approximate 150 initially reported.

“At the Lehigh site, total mortality is estimated at 150, which also is an increase.”

The increase “shows we haven’t come to the end of this resurgence,” he said.

“There were a lot more dead birds at the site last week compared to Jan. 2, whether those birds were infected when they flew in, became exposed there or some of both,” Lau said.

“The resurgence isn’t limited to these sites. We have gotten reports from across the state, though a lot of them are from the Lehigh Valley, which makes sense given it is along snow goose migration routes.

"And we are seeing the highest impacts on snow geese. There have been positive results for Canada geese and red-tailed hawks, as well, but only a couple of each.”

But the Valley is not the only region dealing with bird flu — it’s an issue throughout the United States.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture has online dashboards, showing outbreaks in both commercial and backyard flocks, as well as wild birds.

The former shows 89 flocks have so far been confirmed to have HPAI, affecting 12.9 million birds.

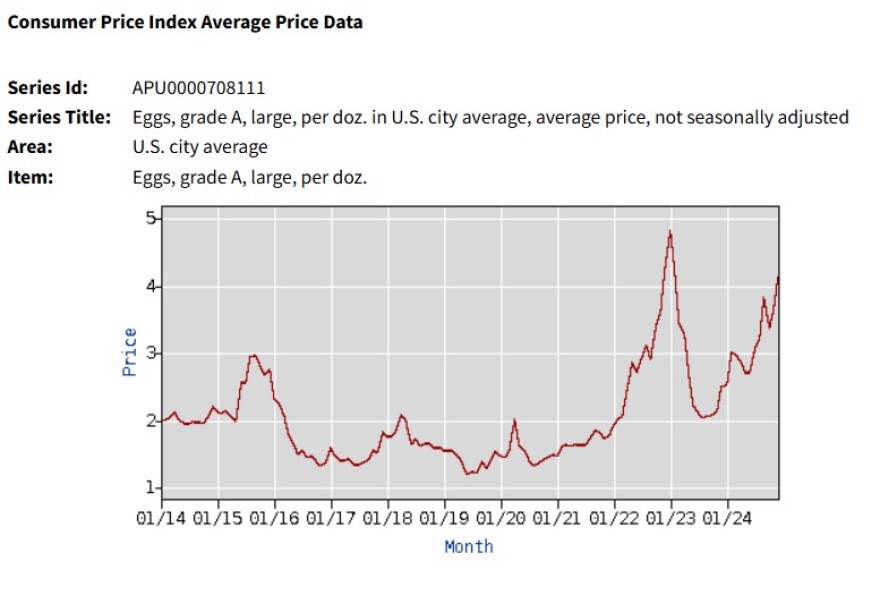

The reach of the disease can be felt in consumer’s pockets. In December 2014, the average price of a dozen grade A large eggs was $2.21, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor and Statistics.

By December 2024, that price nearly doubled, to $4.14.

On Jan. 6, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced the first human death from the virus in the U.S. — a person in Louisiana.

“While tragic, a death from H5N1 bird flu in the United States is not unexpected because of the known potential for infection with these viruses to cause severe illness and death,” according to a news release from the agency. “As of January 6, 2025, there have been 66 confirmed human cases of H5N1 bird flu in the United States since 2024 and 67 since 2022.

“This is the first person in the United States who has died as a result of an H5 infection. Outside the United States, more than 950 cases of H5N1 bird flu have been reported to the World Health Organization; about half of those have resulted in death.”

Even with a recent human death, risk to the public remains low, officials said.

“Most importantly, no person-to-person transmission spread has been identified,” officials said. “As with the case in Louisiana, most H5 bird flu infections are related to animal-to-human exposures.

“Additionally, there are no concerning virologic changes actively spreading in wild birds, poultry, or cows that would raise the risk to human health.”

Last week, the Food and Drug Administration outlined procedures to reduce the chance of domestic cats contracting the virus. Officials said cats can catch it through food, most often unpasteurized milk or uncooked meats.

“Felines, including both domestic and wild cats, such as tigers, mountain lions, lynx, etc., are particularly sensitive to H5N1 and care should be taken to not expose these animals to the virus,” according to a news release.

“Dogs can also contract HPAI, although they usually exhibit mild clinical signs and low mortality compared to cats.

“At present, HPAI has not been detected in dogs in the United States, but there have been fatal cases in other countries.”

Residents should follow the USDA guidelines for handling and thorough cooking of raw meat before feeding, officials said. In addition, animals should also be kept from hunting and consuming wild birds.

‘Death is not the enemy, suffering is’

While this bird flu outbreak might feel similar to the COVID-19 pandemic, this is an entirely different disease — and, unlike COVID, which was a novel virus, bird flu has been studied for years.

“H5N1 has been around at least 25 years that we know of,” Cronin said. “It's not like this just came out of nowhere.

"When it started to spread globally amongst the wild birds, it was just a matter of time before those birds started to infect poultry — backyard poultry, poultry for laying eggs and for food production.

“We always imagined that it would jump to mammals. We just hoped that it wouldn't jump from mammal to mammal, meaning human to human. That's our biggest fear.”

Bird flu can be easily spread through direct contact with an infected animal’s mucous membrane, feces and/or blood.

“When you walk your dog, if they come in contact with a sick bird, or they come in contact with the feces from a sick bird, they can actually get it, and then they can spread it to other dogs or other pets in the house and to their humans,” Cronin said.

“So we're starting to see it very slowly, spread out from the wild birds and Europe to now we're dealing with this right here in the Lehigh Valley.”

Animal rehabilitators, such as Pocono Wildlife, have been working to clear infected birds.

“It is more rampant this time of year, because of migrating,” Schuster said. “It'll start to die down as the birds migrate through.

"The issue is that all these dead birds that are out there laying around and other animals are eating them, they're affected.

“The next one dies, the next one eats it, the next one dies, the next one eats it. It's sort of a domino effect that can happen. It is definitely this time of year. And this is the worst I've seen it.”

In addition to snow geese, they’re “seeing and getting calls about a lot of animals that are not right,” she said, including owls and eagles.

“We're getting videos from the public of sick birds that look like they have it,” she said. “They are staring up into space. Their heads are bobbing back and forth, and if they're flighted, there's nothing we can do to catch them, to help in any capacity.

“Because, for us, death is not the enemy, suffering is. There's no cure for this."Kat Schuster, a licensed wildlife rehabilitator and lead clinic manager at Pocono Wildlife Rehabilitation & Education Center.

“Because, for us, death is not the enemy, suffering is. There's no cure for this. There are different methods being tried, but so far, by the time any of these animals get to rehab, it's usually too far gone.”

The team at Pocono Wildlife depends on donations, which fund their work as well as the tools they need to complete it, like personal protective equipment, or PPE, or stop the spread.

“It's not just snow geese, it's affecting a lot of wildlife, and it can affect the whole ecosystem,” Schuster said. “It's heartbreaking, and it is helplessness, because you can only help so much, and you feel like you're not really helping at all.”

Vaccines, vigilance

Scientists don’t know the origin, or where bird flu came from, Cronin said. Treatments are also few and far between.

“In the United States, until recently, if one bird had it, you had to sacrifice all of them,” Cronin said. “We call it culling. They were just killed because of the possibility that they could spread that to other farms nearby.

“And the way we do farming in this country, one farm is so close to another farm, and you could have a poultry farm next to a pig farm next to a cow farm.

"I hate to use this term right now, because of what's happening in the west, but it can spread like wildfire — just like wildfire.”

While vaccines are in the works for chickens and cows through the USDA, there’s also movement to getting a vaccine ready for people, too.

“These animals are our food sources, and without them, we won't have an ample supply of food,” Cronin said. “And so, we need to be thinking ahead that way and saying, ‘OK, let's save our food supply.’

“Let's save the animal for sure. I'm a huge animal lover, but let's save our food supply, and let's save humans. And, not just that.

"There are a number of people who work with those farm animals who have been infected. Most of the people in the United States with documented H5N1 have been farm workers, and there's probably a whole slew more.

"I mean, I'm sure we have underestimated this, those that have not sought medical attention or testing.”

In July, Moderna, a pharmaceutical and biotechnology company, was awarded $176 million to develop a vaccine for people.

It was funded through the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, or BARDA, within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

"mRNA vaccine technology offers advantages in efficacy, speed of development, and production scalability and reliability in addressing infectious disease outbreaks, as demonstrated during the COVID-19 pandemic," Moderna Chief Executive Stéphane Bancel said in a news release.

"We are pleased to continue our collaboration with BARDA to expedite our development efforts for mRNA-based pandemic influenza vaccines and support the global public health community in preparedness against potential outbreaks."

In the meantime, vigilance and communication are key, local experts said.

“We're in the infancy of this potential pandemic,” Cronin said. “But there are some things that people can do. One of them is don't drink unpasteurized milk.

"If that milk came from an infected cow, there is the potential that you can get exposed that way. Don't give your cat unpasteurized raw milk, either, because cats have died because they have been exposed to the virus through milk.

“You certainly don't want to touch a wild bird … You definitely don't want to go near any sick livestock. And, you want to keep an eye on your backyard poultry.

"If you have backyard poultry, birds flying over can drop infected feces, and that's how backyard poultry can get infected.

“And so, if you think you have infected backyard poultry, you got to suit up and put some PPE on and sacrifice those animals and contact the USDA or the state health department.”

If residents see a dead or sick animal, they should report it to the state Game Commission by calling 1-833-PGC-WILD (1-833-742-9453).

“If nobody is saying anything, we don't know,” Schuster said. “The authorities don't know. So if they see something, call the Game Commission, call a wildlife rehabber and just report it.

“That's the only way we're going to know how far it's spreading.”