LOWER SAUCON TWP., Pa. — As scientists sought to separate PFAS, also known as forever chemicals, from the environment, they studied oceans and rivers.

“They realized that the bottom of dams, where it's foaming up, had a lot more PFAS there than down, deeper in,” said Jeff Travis, vice president of engineering for The Water & Carbon Group. “Then, if you go to an ocean, if you stand where the waves come crashing in, the highest level PFAS is all that foam that comes up — it's loaded with PFAs now.”

With that finding came a workable solution to separate forever chemicals from water — add air.

Officials at the Bethlehem Landfill on Monday cut the ribbon on its $2 million per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, treatment plant at 2543 Applebutter Road in the township. The LEEF System, developed by Australian-based environmental health services company The Water & Carbon Group, is the first of its kind in the U.S.

It removes PFAS using foam fractionation, a process involving air to separate out forever chemicals. Over a series of stages, 99% of PFAS are removed from up to 100,000 gallons of leachate, or water that has flowed through garbage in the landfill, per day.

“Today, we are marking an official opening of the very first fixed plant system in the United States specifically designed to tackle the removal of PFAS, also known as forever chemicals, from raw leachate,” said Astor Lawson, Bethlehem Landfill’s district manager.

“This groundbreaking technology … has already proven to be an incredible asset to our environment and our public health efforts.”

‘A passive receiver of PFAS’

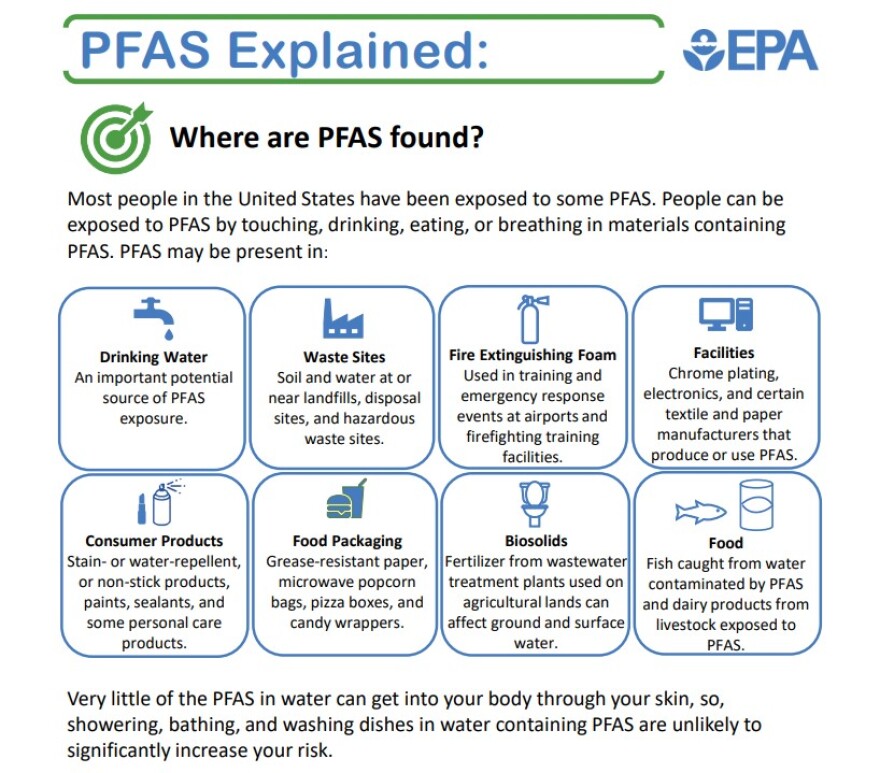

PFAS are a group of manufactured chemicals that have been used in consumer products since the 1940s, but have been nicknamed “forever chemicals” because they are incredibly slow to break down once introduced into the environment and can contaminate groundwater.

And the ribbon is cut! pic.twitter.com/Ld4fAHviKT

— Molly Bilinski, artisanal sentence crafter (@MollyBilinski) November 18, 2024

They have been linked to a variety of health problems, including liver and immune-system damage and some cancers. And, they are incredibly widespread.

The Environmental Protection Agency in March 2023 announced a proposal to set nationwide maximum levels of PFAS allowable in public drinking water. The announcement came about three months after Pennsylvania adopted new regulations, but the EPA’s were almost four times lower.

The EPA’s final standard, announced in April, set a maximum of 4.0 parts per trillion for perfluorooctanoic acid, or PFOA, and perfluorooctane sulfonate, PFOS, individually — two of the most widely used and studied chemicals in the PFAS group.

Environmental advocates lauded the new standard, but it'll be several years before it's enforced.

In the Lehigh Valley alone, PFAS have been recorded in at least five streams, and Emmaus’ efforts to remediate have been costly and well-documented.

For Bethlehem Landfill, the PFAS problem is highlighted in the raw leachate.

“These forever chemicals are found in many household items such as non-stick cookwear, water-resistant fabrics, food packaging and personal care products,” Lawson said. “As a landfill, we are a passive receiver of PFAs.

“When these items are thrown away by consumers, the PFAs end up in the landfill leachate as items break down over time.”

While the EPA does not currently mandate landfills treat for PFAS, officials said the decision was made “to take this important step as an environmental leader in the community and the industry.”

Since bringing the plant online July 1, there have been “remarkable results,” Lawson said.

This system is not just an innovation, it is a vision for the future of sustainable waste management.Astor Lawson, Bethlehem Landfill’s district manager

“The system treats leachate with such precision that PFAS levels are reduced to non-detect levels, well below EPA standards,” he said. “In just a few short [months], we've already seen the system exceed our expectations.

“ … It requires no pre-treatment, consumes minimal energy and leaves behind [a] low volume of residual waste, all while achieving an impressive 99% removal rate of targeted PFAS compounds. This system is not just an innovation, it is a vision for the future of sustainable waste management.”

‘We're just adding air’

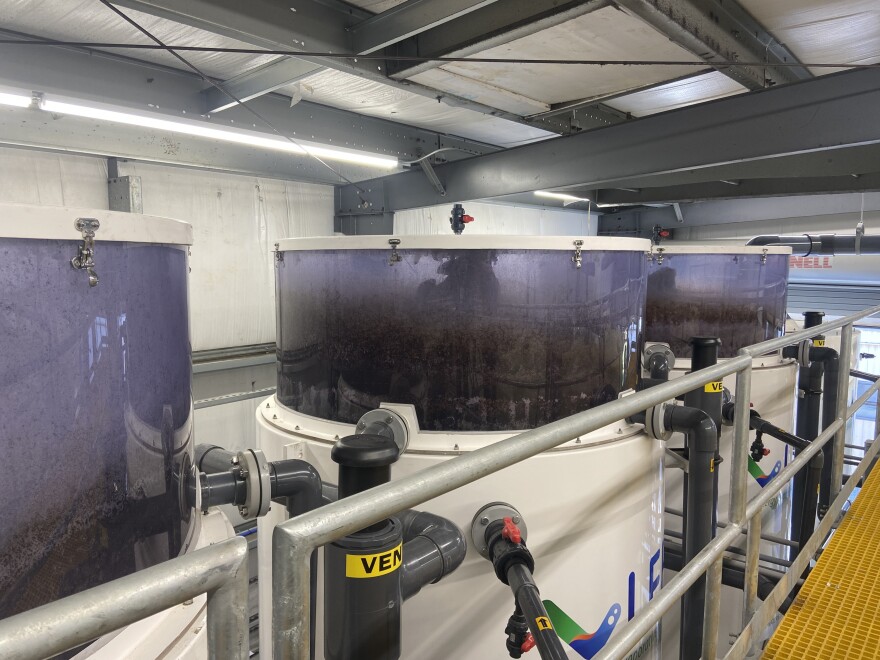

It was loud inside the plant, with metal grated floors below and lines of different size piping running overhead. Safety glasses and earplugs were mandated for entry.

Just inside the doors and to the left, three 14-foot-tall, 6-foot-wide cisterns towered, white except for the very top, where a dark bubbly sludge collected.

“It’s a continuous flow, so we don’t have to stop,” said John Croom, vice president of sales and marketing for The Water & Carbon Group. The company has a similar facility operating for the past two years in Darwin, Australia.

Climbing the narrow steps to the catwalk above gives a view of the tops of each tower, where dark-colored bubbles, pushed from the tank below, collected.

“What's going on here is it's just got air being injected into the vessel, and the air creates foam,” said Travis. “Normally, a leachate has so many chemicals inside of it already that it foams up all on its own.

“So, we don't add chemicals to it. We're just adding air. And the PFAs actually separates itself from the water. It wants to leave the water.”

The PFAS separates from the water through the foam, coming out the top of the cisterns looking like dirty bubbles.

The forbidden cotton candy 😋

— Molly Bilinski, artisanal sentence crafter (@MollyBilinski) November 18, 2024

(Seriously tho — this is PFAS 🤮) pic.twitter.com/kSckF087Ef

“The first vessel will take 80 to 90% of it out, and then whatever's left over, the next vessel takes another 80 to 90%,” he said. “And then by the last vessel, it's just doing a polishing of removal.

“This same process that we see here happens in nature, and that's how we found out about it.”

Once the foam is collected, it gets concentrated down before its final disposal.

For the Bethlehem Landfill, that means it's solidified and sequestered in the landfill. However, just as scientists have created a treatment process, they’re also working on a way to destroy PFAS once and for all.

“That destruction process is still in its infancy,” Travis said. “They're working on it. They're trying to get it cost effective.”