BETHLEHEM, Pa. — Pennsylvania officials last week launched a $4.4 million lead testing and remediation program for schools and childcare facilities across the state.

And while health advocates are happy for recognition of the problem of lead in school water, some say it's so pervasive that action, rather than testing, is what's needed.

“We know the health risks associated with childhood lead exposure," state Department of Environmental Protection Acting Secretary Jessica Shirley said in a news release.

"Which is why we’re committed to seeing it eliminated whenever possible. The WIIN program is a win-win for Pennsylvania’s children because it helps find where the problems are and helps eliminate them.

“Ensuring every Pennsylvanian has access to clean drinking water is a core part of DEP’s mission. By continuing to take action to get lead out of our drinking water, this grant program will promote a healthier, safer commonwealth.”

DEP officials last week launched the Child Care Lead Testing and Reduction grant program. Aimed at schools and childcare facilities, the program provides funding for testing and remediating lead in drinking water in eligible districts.

The funding comes from the EPA’s Water Infrastructure Improvements for the Nation program.

Lead in schools, communities

Schools or childcare facilities must have drinking water sample results showing lead above 5 parts per billion within three years of the date of application in order to be eligible, according to the release.

Recipients may be eligible for reimbursement up to $3,000 for each hydration station installed.

While the program is a step in the right direction, environmental advocates said funding should be directed squarely at remediation in lieu of testing.

“At PennEnvironment, certainly, we feel strongly that the funding should be really laser-like focused on remediation."David Masur, executive director

“At PennEnvironment, certainly, we feel strongly that the funding should be really laser-like focused on remediation,” Executive Director David Masur said.

“These days, remediation is considered the best practice for lead in school drinking water.

“And actually, most experts would tell you to stop testing. Now, that sounds counterintuitive on the surface, but it's because lead in school drinking water has been shown to be so pervasive.”

Lead in school pipes

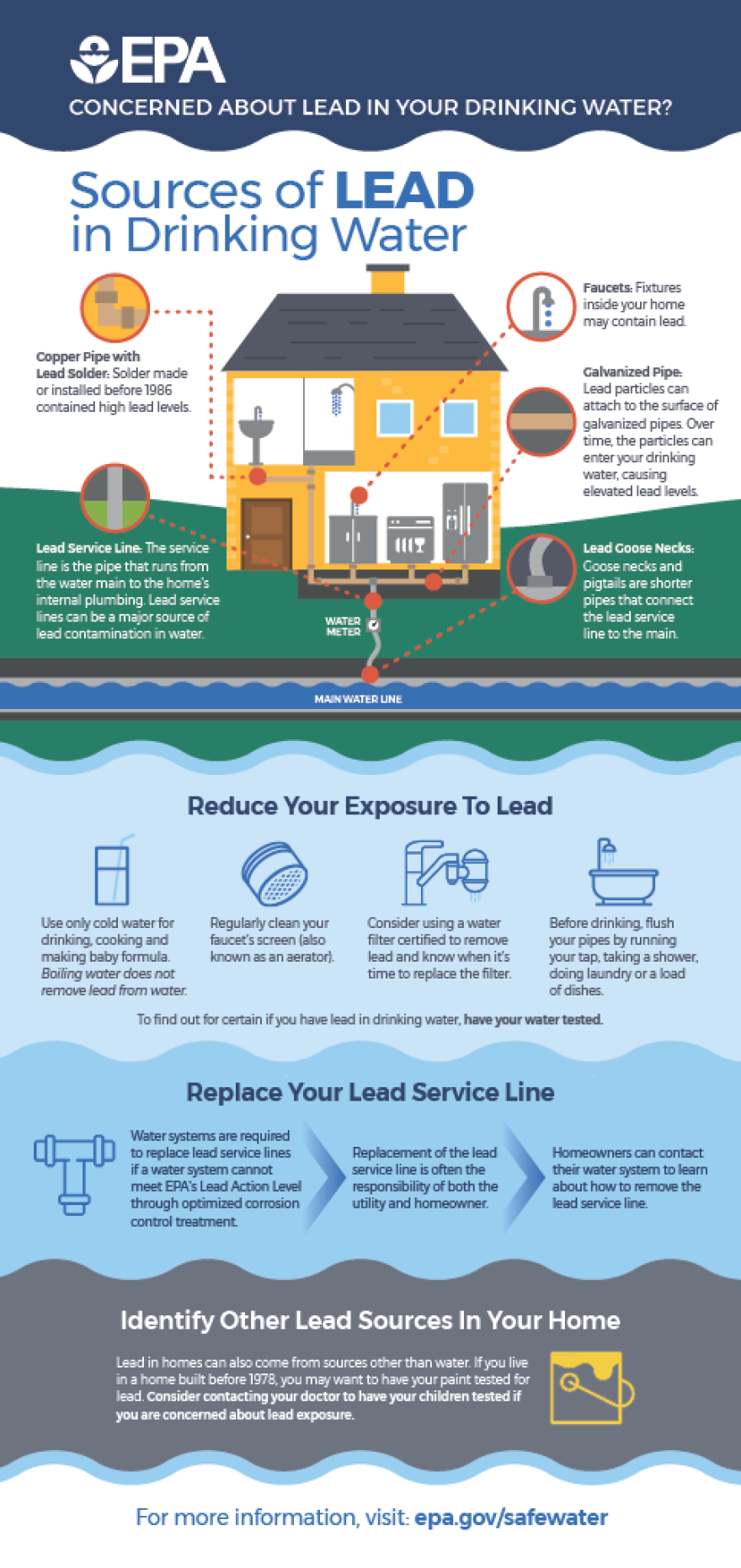

Lead exposure through drinking water has been an ongoing concern throughout the Lehigh Valley, not only for students, but for residents, too.

Exposure to lead — which cannot be seen, tasted or smelled in drinking water — can build up over time, causing a range of health effects, according to the Mayo Clinic.

In children, lead poisoning can cause a developmental delay, learning difficulties, irritability, loss of appetite, weight loss, sluggishness and fatigue, abdominal pain, vomiting, constipation, hearing loss, seizures and eating things, such as paint chips, that aren't food, according to the medical center.

While the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s action level for lead contamination is 15 parts per billion, the agency has “set the maximum contaminant level goal for lead in drinking water at zero.”

There also is state law focused on lead contamination in school drinking water, Act 39 of 2018.

As the law sits now, “schools may, but are not required to, test for lead levels annually in the drinking water of any facility where children attend school,” according to the state Education Department.

“If a school chooses not to test for lead levels, then the school must discuss lead issues in school facilities at a public meeting once a year.”

Lead in communities

School officials aren’t the only local leaders dealing with lead pipes.

The commonwealth ranks fourth of all U.S. states for the most lead pipes, according to EPA's “7th Drinking Water Infrastructure Needs Survey and Assessment.”

The EPA’s Lead and Copper Rule Improvements, published in October, mandated drinking water systems across the United States identify and replace lead pipes within 10 years.

The following month, the Lehigh County Authority sent out letters notifying residents the service lines bringing water to their homes are made of materials that most likely need to be replaced.

Almost 40,000 letters to residents in its service area were sent.

However, the rule so far this year has seen back-to-back attempts to repeal it through joint resolution.

Lead in Valley schools

In September, PennEnvironment Research & Policy Center published its study “Lead in School Drinking Water.”

For the project, researchers submitted Right-to-Know requests to nine school districts across the commonwealth, including Bethlehem.

They found Bethlehem Area School District was lacking in both lead testing and transparency to residents.

“Our report showed districts are sort of willy-nilly about following [Act 39] at all or correctly,” Masur said.

“What we do know is, when districts do test for lead, over 90 percent of school districts are reporting that they're finding lead in their drinking water.

“So, when you're at 90 percent lead contamination tests by district, why would you keep testing? Nine out of 10 times, districts will find lead.”

In the Valley, six local school districts have reported elevated levels of lead in their water since 2018.

They include Allentown, Easton Area, Parkland and Southern Lehigh school districts, and Bethlehem Vocational-Technical School and Carbon Lehigh Intermediate Unit 21.

Since 2020, Bethlehem, Southern Lehigh, Parkland and Allentown school districts all have reported elevated levels of lead in drinking water to the DOE, as well as remediation plans.

'Bigger part' is remediation

LehighValleyNews.com reached out to each of those four districts, asking if officials planned to apply for the Child Care Lead Testing and Reduction Grant Program.

Only officials from Allentown and Bethlehem responded, both affirmatively.

“A larger district, here in Bethlehem, it costs us maybe $2,500 to do our testing annually — ballpark,” said Mark Stein, Bethlehem Area School District's chief of facilities and operations.

“We'll take any savings we can find, but I guess the bigger part for us would be the remediation part. So if there's money available to fix stuff that gets our attention, then we'd obviously want to learn more about it.”

In addition to annual testing — noting the vast majority have been negative — the district over the past several years has replaces existing fountains with filtered hydration stations, Stein said.

“This past year, we've added several filtered fountains in some of the older buildings,” he said. “Generally, we’ve been replacing fixtures.

“If we run across an old fixture that might have brass in it, we'll swap that fixture out and put a new, lead-free fixture. And then we come back and retest, and it's fine.”

‘The best way this program should work’

While providing the funding is a good start, there are ways to improve the program, Masur said, including getting rid of the testing requirement and threshold for districts.

“The release says districts that find lead at 5 ppb or higher can apply,” he said. “That 5 ppb is very deceiving, because that is not a health-based standard for lead.

"It's just a political pin that was dropped into the law. Lead, as we know, is unsafe at any level. That is not in debate.”

The problem with testing, he argued, is it can give districts a “false sense of security” through false negatives, or inconsistent results.

“Lead is a moving contaminant, so if you don't find it today, if you go back in a year, it may test really high for lead, which is crazy,” Masur said.

“And you see that in some of the tests that school districts are reporting. You'll see that one year, an outlet doesn't test for lead at all, but the next year tests really high, because lead responds to a set of environmental factors that makes it change.

“It's one more reason not to test, because you can get these tests that come back negative for lead one day and think, ‘Oh, everything's fine.’

"And then the district to go back in a month, a year, two years and find really elevated levels of lead and go, ‘Wait. How did that happen?’

“This is one more reason why you have to move away from testing, because it gives a false sense of security.”

“If the DEP just said, ‘If you have a pre-2014 drinking fountain and want to replace it, we have the money. Apply for the funds’ — that would be the best way this program should work."PennEnvironment Executive Director David Masur

Until the Reduction of Lead in Drinking Water Act of 2014 was passed into law, amending the Safe Drinking Water Act, national standards allowed fountains, faucets, pipes and plumbing to contain a significant amount of lead.

If districts know their equipment is older, testing wastes time and money, Masur said.

“If the DEP just said, ‘If you have a pre-2014 drinking fountain and want to replace it, we have the money. Apply for the funds’ — that would be the best way this program should work,” he said.