LEHIGH TWP., Pa. — Almost 12 hours into fighting a Nov. 2 fire that engulfed Blue Mountain, officials pulled the plug and recalled the crew.

It was too dangerous to fight the growing blaze at night.

“I kind of felt a little defeated, because we didn't get it,” township firefighter and safety officer Lee Boehning said.

“But, you know, at the same token, a lot of our guys were out Friday most of the night, then they got back up and went back Saturday morning and we got called to that.

“A lot of our guys were fatigued, and the last thing you want to do — you don't want to get hurt up there.”

“I've been on a bunch of mountain fires up there, and that was probably one of the worst ones I was on up there just because of the fuel load. If it wasn't for the fuel load up there, I think we would have probably stopped it [that first day] somehow.”Firefighter and safety officer Travis Wuchter

It’s been almost a month since the Blue Mountain fire, also called the Gap Fire, erupted near Route 248 in Lehigh Township.

Hundreds of firefighters poured in from across the state to help the township’s volunteer crew, and donations from residents overwhelmed officials so much that they had to ask them to stop.

During the seven days fighting the blaze before it was marked fully contained and handed over to state officials, firefighters worked both day and night shifts, many making arrangements with their day jobs by either taking vacation or sick time.

The weeks of drought conditions, along with past revegetation efforts on the mountain, created a bounty of tinder-dry fuel, firefighters said.

Once the fire started, it was hard to stop.

“I've been on a bunch of mountain fires up there, and that was probably one of the worst ones I was on up there just because of the fuel load,” firefighter and safety officer Travis Wuchter said.

“If it wasn't for the fuel load up there, I think we would have probably stopped it [that first day] somehow.”

‘Fire on the mountain’

Calls for service because of brush fires started Friday, Nov. 1, hours after the National Weather Service in Mount Holly, New Jersey, issued a red-flag warning — put in place when the risk of fire danger is highest — because of the dry, windy conditions.

That same day, the state Department of Environmental Protection declared Lehigh and Northampton counties in a drought watch after very little rain in September and October.

Township firefighters responded to several smaller brush fires Friday out of the area, before getting the call that a 15-acre brush fire was burning, township Fire Commissioner Richard Hildebrand said.

Crews worked that fire until almost midnight.

Then, about 1:40 p.m. Saturday, Nov. 2, another call came in — “fire on the mountain,” Boehning said.

“It came in as a brush fire on the mountain, and that's usually never a good time,” Hildebrand said. “I knew it was going to be a couple day fire just from the location, the weather conditions, the drought, all those things.”

The fire was about 700 feet up the mountain’s rocky surface — challenging terrain for anyone, let alone firefighters carrying the equipment needed to fight brush fires — rakes, axes, chainsaws and even leaf blowers.

“We sent guys on foot up from the bottom,” Hildebrand said. “They hiked up. They had hand tools with them, [but] no water. They were scouting to get a size up.”

A growing blaze

At the same time, another crew came across the top of the mountain from Little Gap with trucks and water. However, the road only goes so far. When it ended, they got out to walk, cutting their way in with chainsaws.

“The initial crews started walking up, and [the fire] was 1 to 2 acres,” Hildebrand said. “By the time they got there, it was 4 to 6 acres.

“And it was moving pretty quick, because it was burning uphill and expanding in three different directions.”

The terrain proved to be a bigger problem than expected, especially for one of their tactical trucks.

“It's perfect for the mountain, but isn't so perfect for rocks, because it ripped the airlines out from underneath the truck so it was dead in the water,” Hildebrand said.

“And fire burning toward it, so we kind of realized that we're up against some trouble here. The fire’s now up to about 20 acres and it was still growing.”

Crews tried to establish fire lines and brought in bulldozers. They started making fire breaks around the blaze.

As night fell, the fire grew to 40 acres.

'Growing and growing and growing'

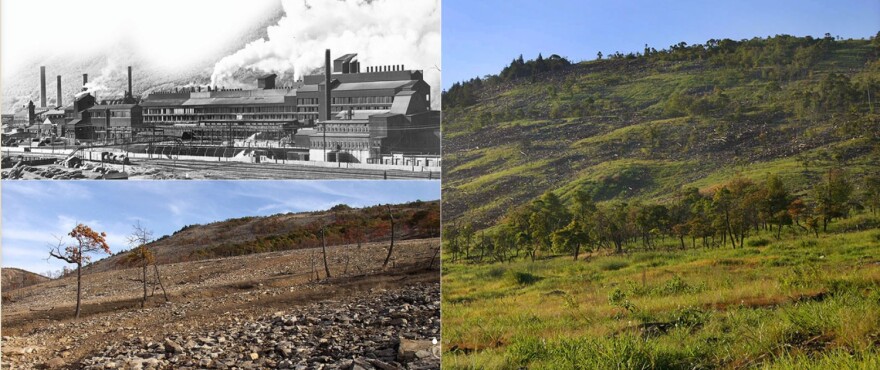

Not only was the terrain an issue, but decades-long revegetation efforts had been successful, creating a thick understory.

With the drought, all that growth turned into fuel.

That part of Blue Mountain is part of the Palmerton Zinc Pile Superfund site. It was unintentionally stripped of vegetation over about 100 years by the New Jersey Zinc Co., which set up a zinc smelting operation in nearby Palmerton in 1898, which damaged the environment slowly over time.

Revegetation efforts began in the 1990s, with several rounds of seeding.

As part of the reclamation process, there also are areas of the mountain surrounded by 12-foot fences called “resource islands” — another obstacle of which firefighters had to be mindful in addition to the terrain and the seemingly endless amount of tinder-dry fuel.

“What we saw on the bottom is, this thing is just growing and growing and growing,” Hildebrand said. “And it got to the point where I'm like, ‘Guys, I don't care what you do. You're not putting this fire out. This is bigger than big.’

“We pulled everybody back. We regrouped.”

“At the new command post, we could see the whole entire broad section of the mountain, and that really facilitated a good outcome in the future for the evolutions that transpired afterward, because we just went days and days and days.”Richard Hildebrand, township fire commissioner

Late Saturday, helicopters started carrying water from the Lehigh River to dump on the flames, but were only able to be in the air for an hour or two before they had to return.

Firefighters were sent to homes on nearby Timberline Road to monitor fire breaks.

The command post was moved from the railroad bed to the municipal complex.

“At the new command post, we could see the whole entire broad section of the mountain," Hildebrand said.

"And that really facilitated a good outcome in the future for the evolutions that transpired afterward, because we just went days and days and days."

I’m at the Lehigh Township Municipal Complex for @LVNewsdotcom, where emergency responders have staged as they fight the wildfire on Blue Mountain. pic.twitter.com/OEc8KYiicS

— Molly Bilinski, artisanal sentence crafter (@MollyBilinski) November 4, 2024

'A game plan was formulated’

Fighting a brush fire or wildfire is different from fighting a house fire. The latter is generally preferable, just because of access.

It’s a lot easier to surround a fire on a city street than on the side of a steep mountain covered by thick underbrush.

“I'll fight three or four house fires in a week before I'll fight one of them,” Boehning said. “We're carrying everything on our backs. We're on our own, basically, until we get out.

“It's a different animal and it takes unique people to do it.”

Unlike a house fire, where fighters generally respond wearing heavy suits and gear, a brush or wildfire requires a different set of tools, as well as specialized skills and training.

“You got to be a billy goat, a mountain guy,” Hildebrand said. “You’ve got to have lightweight forestry stuff so you can crawl and get around.

“You're just looking to get hurt if you have that other equipment.”

After pulling back from the mountain late Saturday, crews rested and ate while officials came up with a plan.

By early Sunday morning, they were back at it again.

Part of fighting a wildfire is starting more fires — something that might seem counterintuitive, but works by getting rid of a fire’s fuel sources.

Through backburning, crews mapped out a boundary line and starved the fire of its ability to spread further.

Unfortunately, the fire was jumping the breaks, growing and spreading.

Efforts start working

Sunday and Monday, Nov. 3 and 4, were focused on containing the blaze as best they could. Firefighters kept working the breaks.

Imagine 20 firefighters with rakes, Assistant Chief Brian Krische said, moving debris and soil out of the way to create a cleared path, separating the fire from its fuel.

“You have a guy with a leaf blower in the front, and he's blowing the clearing for the path,” he said. “Or you might have a guy with a chainsaw leading first, or a hedge trimmer first.

“You take down brush, and we just form a train. Everybody takes one swipe, take a step, take a swipe, take a step, take a swipe.

"You're not sitting there in one spot. It's a constantly moving production.”

By Sunday afternoon, 150 acres were scorched.

On Monday, a crew was assigned to trek up the mountain with a fire hose, laying it down every 200 feet. The water, in conjunction with the backburn efforts, started working.

On Tuesday, Nov. 5, even though the fire had grown to 577 acres, it was more than half contained.

At that point, officials started “mop up” work — patrolling the fire breaks and watching out for any hot spots.

‘My jaw drops’

Fighting the fire took a lot of coordination as mutual aid and donations came rolling in. Hundreds of firefighters responded from state and local agencies.

Asked how many local departments responded, Hildebrand said it’d be easier to list the counties: in addition to crews from Lehigh and Northampton counties, firefighters came from Carbon, Monroe, Schuylkill, Berks and Bucks counties.

Township and county officials helped with logistics, and the state Department of Conservation and Natural Resources sent a team, too.

The DCNR put out a statewide “all call,” said Janet Sheats, an EMT and firefighter. Firefighters responded, some from as far as Pittsburgh.

Because the Lehigh Township department is all volunteer, as are the majority of firefighters in Pennsylvania, many of the crew members had to return to work after their shifts fighting the. Or they’d need to use paid time off, if it’s available.

“We walked down in front of the municipal building, and you look and see 30 cars down that road and 30 cars coming in. They have cones set up. We’ve got truckloads coming in."Brian Krische

During the early morning hours on Sunday, Krische put out a call on social media, telling residents who were asking how to help to donate water.

“I didn't think anything of it,” he said. “Never in a million years would I have thought.”

But once that faucet was turned on, it was almost impossible to stop.

“We walked down in front of the municipal building, and you look and see 30 cars down that road and 30 cars coming in. They have cones set up. We’ve got truckloads coming in.

“My jaw drops.”

‘Times we need help, too'

Sheats took the reins and organized donations while keeping firefighters fed.

Donations and supplies are piled high at the municipal complex. pic.twitter.com/IiPhxzcSAh

— Molly Bilinski, artisanal sentence crafter (@MollyBilinski) November 4, 2024

“We were actually unloading vehicles for [residents] so that we can get them in, get them out, keep them moving,” Sheats said. “Then, all of sudden, hot food was starting to show up.”

Less than 12 hours after Krische’s original call, he posted again, asking residents to keep what they have. Donations kept rolling in.

“I knew I couldn't be up there, but it was my way of being with my team.”Janet Sheats

“Physically, I couldn't be up on the mountain, but I wasn't about to leave these guys,” Sheats said. “I knew I couldn't be up there, but it was my way of being with my team.”

They set up crew meals — breakfast, lunch and dinner each day — for about 150 people.

“I was so overwhelmed by the fact that people were so supportive of what we were doing,” Sheats said. “We do this all the time, and we don't expect anything.”

Water — dropped off by the case — was organized onto pallets. Firefighters could “go shopping” in the makeshift commissary, picking up whatever they needed — personal hygiene items, headlamps, socks, gloves and more.

Residents dropped off homemade and store-bought meals — sandwiches from chain restaurants, chili and baked ziti — requiring a refrigerated truck.

There was so much left over, the fire company ended up donating it back to the community, opening up the firehouse for residents to “shop” before sending the remainder to Northampton Area Food Bank.

“We took what we needed, and the rest we don't want to see go to waste,” Sheats said. “And that's something I think we really do pride ourselves on giving back, but there's times we need help, too.”

‘We just have to wait’

More than three weeks after the fire erupted, it’s still not officially extinguished — yet.

Officials announced on Friday, Nov. 8, the fire was 100% contained, with the expectation the fire would continue to smolder without a soaking rain — something the Valley has yet to see.

From there, officials from the DCNR’s Bureau of Forestry took point on the fire.

As of Friday, Nov. 22, the fire was considered under control, said Greg Reese, a fire investigator with the bureau.

“But that does not mean it's extinguished,” Reese said. “You still have active fire and smoke and smoldering, and things burning internally. We still have the fire controlled until we get some type of rain.”

A wildfire is contained when firefighters have a perimeter around it, controlling the area burned and preventing the fire from spreading further. A fire is extinguished when the flames are completely out.

“We just have to wait,” Reese said. “Wait for a larger accumulating rain, or until we get into a really good wet pattern that we feel comfortable.”

The investigation into the fire is ongoing, with no point of origin or cause yet determined.