NAZARETH, Pa. — A couple of weeks ago, one of Glenn Myster’s clients called him worried — the trees on the client's borough property were showing signs of disease.

- Beech leaf disease has spread to the Lehigh Valley

- The disease can prove fatal in American beech trees

- There is no known cure and few treatment options available

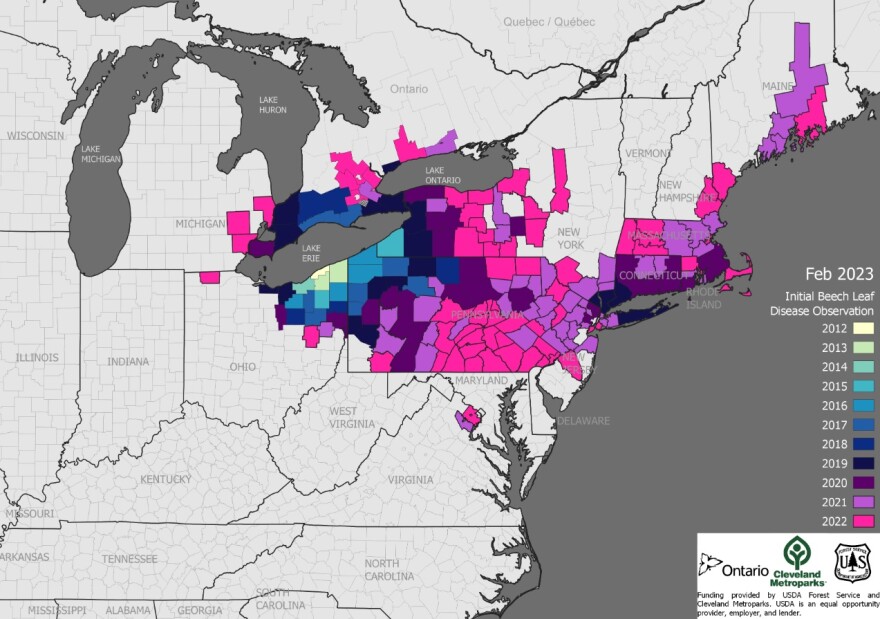

“I went out there and I confirmed that she indeed does have beech leaf disease,” said Myster, arborist and owner of Myster Tree and Shrub Service. “I'm sure that by now it's in every county in the state, even if it hasn't been found in every county — it's the way that it's spreading.

“I'm sure that it's completely across the state, and it's in, of course, Ohio and New Jersey and New York, and it's spreading. It's phenomenal how quickly it's spreading.”

Beech leaf disease, a relatively new and deadly threat to the American beech, is in the Lehigh Valley.

However, because there’s so little known about it, arborists and experts are stuck in what they’ve called a “wait-and-see” situation as researchers monitor the damage the disease can cause, how it spreads and in what ways, if at all, it can be managed.

“It's spreading like wildfire,” Myster said. “And it is a pretty devastating disease.”

‘It can prove fatal to 90% of saplings’

First discovered in northeastern Ohio in 2012, the U.S. Department of Agriculture has described beech leaf disease as “a scourge that is killing trees by the thousands in northern states east of the Great Plains.” In Ohio alone, experts estimate the economic and environmental cost of the loss of the beech is $225 million.

Pennsylvania’s forests are vulnerable, with scores of beech trees. Known for its smooth, light gray skin-like bark and dense, hard wood, healthy beech trees can live up to 400 years.

It’s different from beech bark disease, a canker disease caused by the Nectria fungus, that is also present in the commonwealth. Symptoms of beech leaf disease include the sudden appearance of dark green bands between the veins of the tree’s lower leaves that eventually spread throughout the tree.

“The damaged leaves fall off and the tree is forced to grow new ones,” according to the state Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. “The energy cost of this regrowth eventually results in the death of the tree … In places where the disease is established, it can prove fatal to 90% of saplings.”

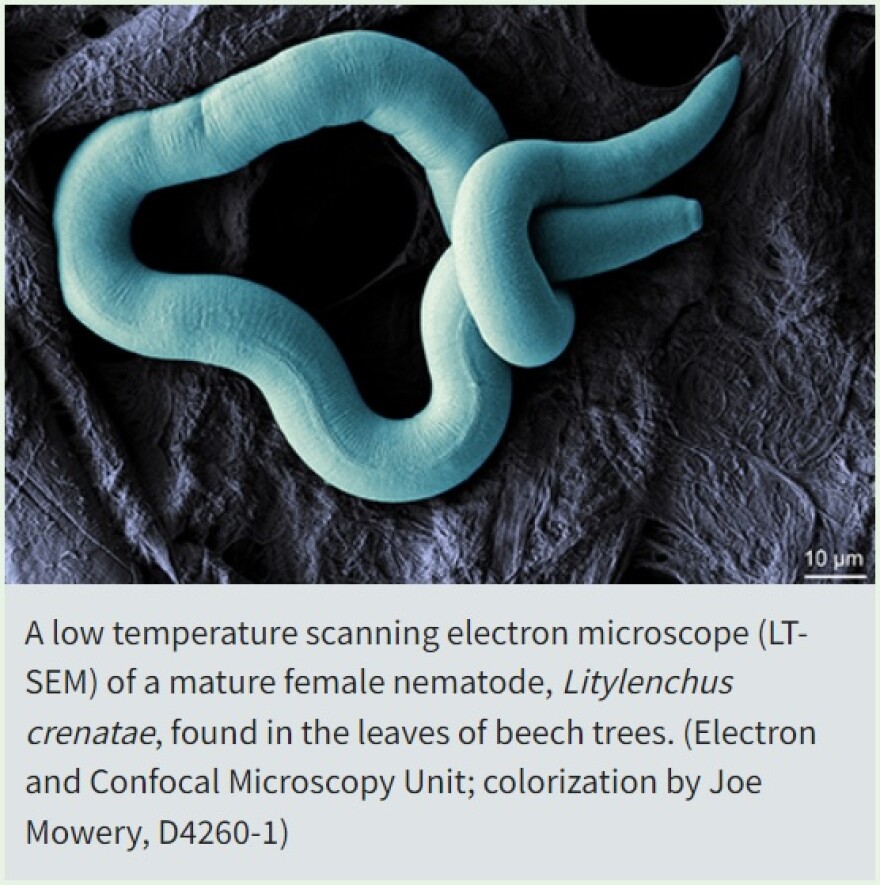

An invasive species of nematode, a microscopic worm, has assumed at least part of the blame.

“The nematode, Litylenchus crenatae, is consistently found in infected trees so it's consistently been associated with it,” said Emelie Swackhamer, a horticulture educator at the Montgomery County Penn State Extension office. “Now at the same time, they think bacteria or fungi might also be involved.”

In order to prove the cause of a plant disease, scientists must satisfy Koch's postulates, four criteria designed to establish a causal relationship between a microbe and a disease.

“We don't really know yet, but it's most likely it's these nematodes moving around.”Emelie Swackhamer, a horticulture educator at the Montgomery County Penn State Extension office

“They have found some bacteria and fungi in infected leaves, not as consistently as the nematode, but it looks very likely that it's mostly and probably the nematode,” Swackhamer said. “So bacteria and fungi could be making it worse.

“We don't really know yet, but it's most likely it's these nematodes moving around.”

In the meantime, the disease has shown to kill infected trees at different rates, depending on size.

“In what we've read from other research-based information sources is that it can kill younger trees faster and it can kill older trees in six to 10 years,” she said.

‘The best we can do right now is to just keep the trees alive’

When a new disease appears in plants, it can be a research problem that presents similarly to an invasive species cropping up, Swackhamer explained.

“To get research-based information about any problem, you need time,” she said, recalling how the state studied spotted lanternflies over several years, and many of those studies continue. “As we continue to have new species and problems, pests and diseases moving in, the researchers need time to react to it and you know it doesn't give you answers in the beginning.”

And those answers arborists and homeowners are looking for right now are treatment options, which are few. But keeping trees healthy is important, especially in the Lehigh Valley, where an abnormally dry spring led up to a statewide drought declaration.

Different nematicides, a type of chemical pesticide used to kill plant-parasitic nematodes, have been tried, but results have not been encouraging, Swackhamer said. In the one treatment that is showing promise, supply chain issues are blocking production and distribution.

“The only real alternative we have right now is there's a group of products that are called phosphonates,” she said. “You apply them to plants, and it kind of boosts their immune system. It's usually something that a professional would do. But they've had some encouraging results in one year of study.”

Myster said he’s been treating infected trees with a phosphorus acid type of fungicide.

“What that does is it reduces the number of nematodes in the leaves but it doesn't eliminate them,” he said. “We can treat the tree and we can hopefully keep it alive and keep it in reasonably good health and hopefully, down the road, sometime soon, a more effective, more long term treatment is going to become available.

“But the best we can do right now is to just keep the trees alive and going until we have some better treatment options.”

But even if a treatment becomes available, it probably won’t be economically feasible to treat the tens of thousands of beech trees across Pennsylvania. A natural control could help, Swackhamer said.

“Hopefully something in that microbial community in these forests decides that the beech leaf disease nematode is a food source and we don't know if that's going to happen, but that sort of situation often does occur with these invasive problems,” she said.

In the meantime, patience — and more research — is key.

“It's a wait-and-see situation,” Swackhamer said. “And it will unfold over the next few years — time will tell.”