BETHLEHEM, Pa. — Testing for lead in students’ drinking water isn’t just a matter of following state law, Chrysan Cronin said Wednesday.

“In an age where we are aware of the importance of creating safe learning environments, regular lead testing in schools is not just a regular regulatory necessity, but a fundamental measure to ensure the health and wellbeing of our children,” said Cronin, associate professor and director of public health at Muhlenberg College. “In schools, where children spend a significant portion of their day, ensuring that the water and surrounding environment are free from lead — it's not just a matter of compliance, but a moral obligation.

“The health implications of lead exposure are well documented, leaving no doubt that even minimal lead exposure can have harmful and irreversible effects on children's health and development.”

Cronin, along with a handful of other local officials and advocates from the PennEnvironment Research & Policy Center, on Wednesday held a news conference at the city’s Sculpture Garden announcing the nonprofit’s new report, “Lead in School Drinking Water.”

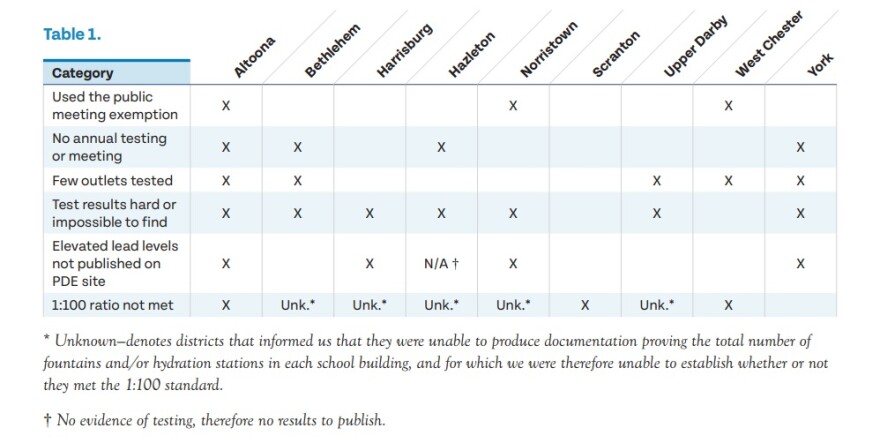

To complete the almost 30-page study, PennEnvironment submitted Right-to-Know requests to nine school districts across the commonwealth, including Bethlehem.

The city school district, with almost 13,000 students enrolled, was found lacking in both lead testing and transparency to residents, according to the report.

In a response posted to the district's website Wednesday, school officials said they have proactively tested drinking water sources for lead.

"Since 2019, the district has taken over 600 water samples to test various drinking water sources for lead from within all facilities — not just schools," according to the message. "Except for 2021, the district developed a testing plan and tested drinking water sources in each kitchen and at least two drinking fountains in each school.

"While the PennEnvironment report suggests the quantity is not sufficient, it also acknowledges it satisfies the requirements of the law."

When testing was completed, results were reviewed during a public meeting, the minutes for which are available for public review, according to the response.

“Our study shows that Pennsylvania school districts regularly put children at risk of being exposed to lead, a well-documented contaminant, in school drinking water by violating state law, skirting reporting requirements and avoiding best practices,” said Flora Cardoni, deputy director of PennEnvironment. “ … The medical research is crystal clear that there is no safe level of lead, especially for children.

“It leads to learning disabilities, hearing and speech problems, affects brain development and lowers IQ. Sadly, for Pennsylvania parents, teachers, students and community members, getting information to know if your local school district is implementing best practices to address the threat of lead in school drinking water can be a near impossible task.”

‘Get the Lead Out’

Lead, especially in the pipes that deliver water to residents and students, has been a cause for concern in the Valley and across the state.

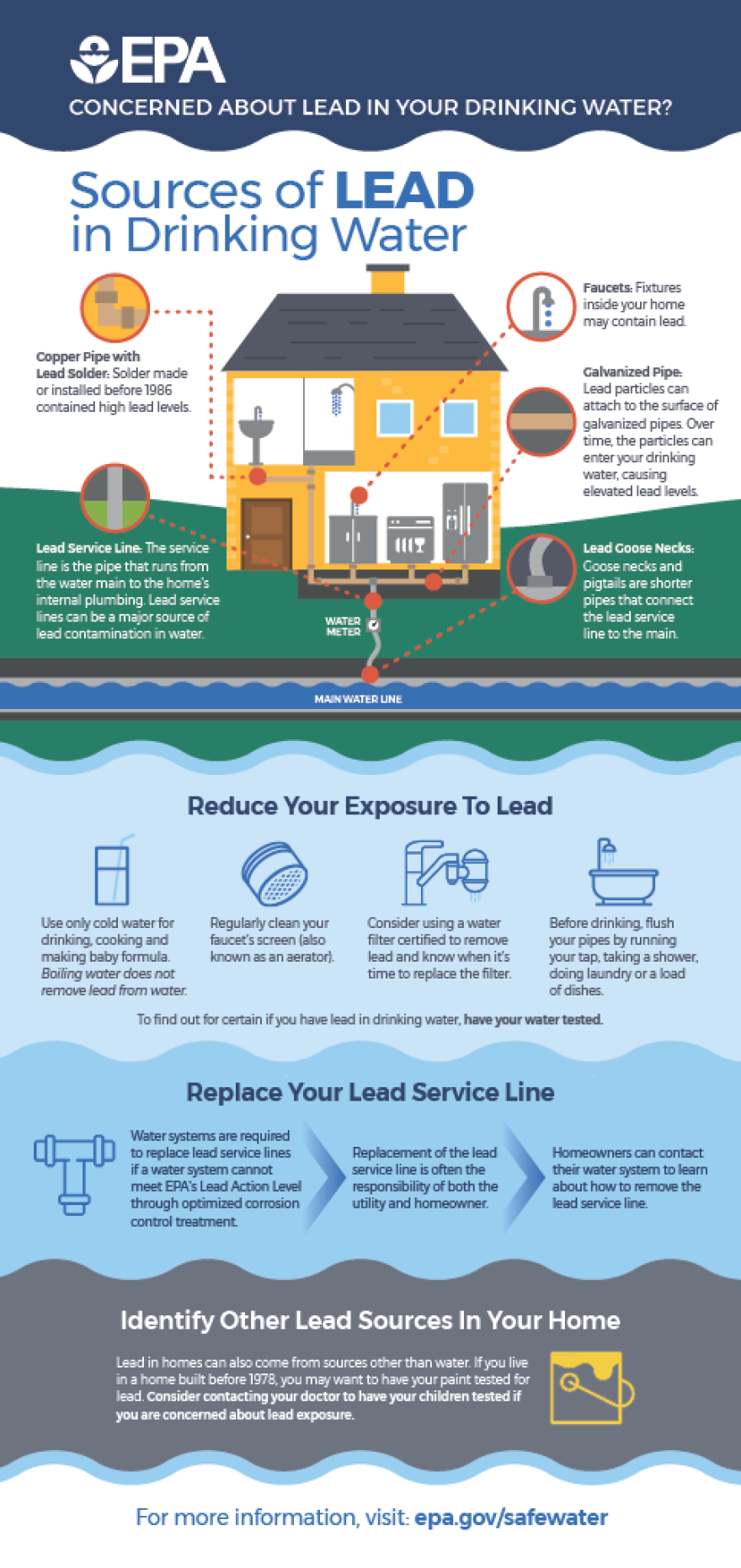

While overall exposure to lead in tap water over the last two decades has decreased, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, lead pipes, faucets and plumbing fixtures still exist in some places, and can increase risk of lead exposure.

Exposure to lead — which cannot be seen, tasted or smelled in drinking water — can build up over time, causing a range of health effects, according to the Mayo Clinic.

In children, lead poisoning can cause a developmental delay, learning difficulties, irritability, loss of appetite, weight loss, sluggishness and fatigue, abdominal pain, vomiting, constipation, hearing loss, seizures and eating things, such as paint chips, that aren't food, according to the medical center.

While the Environmental Protection Agency’s action level for lead contamination is 15 ppb, or parts per billion, the agency has “set the maximum contaminant level goal for lead in drinking water at zero.”

A year ago, PennEnvironment’s Get The Lead Out report gave Pennsylvania an “F” grade “for the inadequacy of the state’s policies aimed at stopping pervasive lead contamination of schools’ drinking water.”

Earlier that year, the commonwealth ranked fourth out of all U.S. states for the most lead pipes, according to the Environmental Protection Agency’s “7th Drinking Water Infrastructure Needs Survey and Assessment.” Florida, Illinois and Ohio were the only states to rank higher.

In the Valley, six local school districts have reported unacceptable levels of lead in their water since 2018, including: Allentown, Easton Area, Parkland and Southern Lehigh school districts, and Bethlehem Vocational-Technical School and Carbon Lehigh Intermediate Unit 21.

The state Department of Education earlier this year announced $75 million in public school environmental grants to address lead and asbestos, along with other environmental contaminants.

LehighValleyNews.com surveyed the region’s 17 school districts, asking administrators if their district applied for the funding. Only five districts responded, with two districts, Allentown and Whitehall-Coplay, answering affirmatively.

Whitehall-Coplay Superintendent Robert Steckel said the district applied for about $20,000 to assist with partial asbestos abatement, part of the conversion of the old Gockley Elementary School to the Whitehall-Coplay Education Center.

Mark Stein, Bethlehem Area School District’s chief facilities and operations officer, said the district didn’t apply for the funding, adding officials “found that we did not have any projects that matched up with the goals of the grant.” However, the district did apply for the Public School Facility Improvement Grant Program.

‘May, but are not required to’

While there is state law focused on lead contamination in school drinking water, Act 39 of 2018, it doesn’t go far enough, advocates argue.

As the law sits now, “schools may, but are not required to, test for lead levels annually in the drinking water of any facility where children attend school,” according to the state Department of Education. “If a school chooses not to test for lead levels, then the school must discuss lead issues in school facilities at a public meeting once a year.”

“I want to know if there is definitively lead in the water. I want to know how many drinking fountains and hydrating stations are in each school, and I want them accounted for.”Northampton County Controller Tara Zrinski

Northampton County Controller Tara Zrinski, who has a son in the Bethlehem Area School District, said she wants more transparency from school officials.

“The fact that Act 39 created in 2018 only requires voluntary testing, and, as an alternative, requires only that lead issues be discussed in meetings is very bothersome to me,” said Zrinski. “I want to know if there is definitively lead in the water. I want to know how many drinking fountains and hydrating stations are in each school, and I want them accounted for.”

PennEnvironment researchers said the law “is demonstrably failing at the task it was designed to do,” describing it as a “test and fix” approach.

“Not only does this law rely on antiquated practices that are no longer believed to protect children from this harmful contaminant, it also contains major loopholes that make it even more difficult to know the extent of the problem or empower parents, community leaders and elected officials to properly address risk where it does exist,” according to the report.

Bethlehem Area School District had years when they neither conducted testing nor discussed lead at a public meeting, according to the report. And, when testing happened, it involved just three outlets — a kitchen faucet and two water fountains in each of its schools, with certain buildings testing just one water fountain — in each of its 22 schools.

PennEnvironment officials were unable to find any discussion of lead in drinking water on the district’s website, either. However, researchers found some references to lead testing in board meeting documents.

“In the case of Bethlehem, some results of lead testing were accessible in, or via links contained in, these meeting minutes — technically publicly available, but very hard to find,” according to the report.

In addition, the district did not have documentation showing the total number of fountains/hydration stations in each school building, even though state code dictates education facilities have one water foundation for every 100 occupants.

They weren’t alone. Only one of the nine districts, York, was able to produce documentation demonstrating compliance with the 1:100 ratio.

“Test and fix” vs. “filer first”

The “test and fix” approach to lead contamination isn’t working, and advocates argued instead for a “filer first” solution.

“Ultimately, Pennsylvania's lax requirements around lead in school drinking water, combined with this non-compliance by school districts, like Bethlehem, are putting the commonwealth's children at risk,” Cardoni said. “Every Pennsylvanian parent should be able to expect that their school district is protecting their kids from the threat of lead in school drinking water.”

Districts should also follow the example of districts in Pittsburgh and Philadelphia, she said, which have already started replacing all their school fountains with lead-filtering models.

In addition, policy change is needed, PennEnvironment researchers argued in the report, as well as during the news conference.

“To properly protect our kids’ health, the state’s existing laws, demonstrably inadequate in mitigating these risks, must be replaced with strong, enforceable lead remediation and testing requirements,” researchers said in the report’s conclusion. “Policymakers must replace the state’s current ‘test and fix’ approach, as enshrined in the poorly designed Act 39 of 2018, with one that requires prevention at every tap used for drinking, cooking and beverage preparation in our schools.”

Senate Bill 986, if passed, would require all school districts across the state to implement this filter first program and replace their old drinking water fountains that pose a risk of lead contamination with lead filtering hydration stations and drinking fountains.

“This legislation also includes funding to help Pennsylvania school districts cover the cost of installing these hydration stations, so that we can protect kids' health,” Cardoni said, adding that districts will move forward without a state mandate.

“ … There are some school districts across the state that are leading by example and doing this voluntarily to protect kids. Of course, we hope that other school districts will follow their lead.”