- The state has updated its definition of 'environmental justice areas'

- Officials say the new definition will help them prioritize resources

- The policy could be tweaked before it takes full effect

BELLEFONTE, Pa. — Pennsylvania has updated the criteria for how it defines “environmental justice areas” — communities more vulnerable to climate and health risks and that get special attention from the state.

About 2.3 million people live in one of these areas under the state Environmental Protection Department’s revision of the 20-year-old environmental justice policy, down from 3.7 million previously.

Officials argue the update and the new way it identifies the communities will help it prioritize resources and improve communication about permits and projects under the department’s purview.

The policy, which took effect this fall but could be further tweaked before taking full effect, outlines considerations DEP should make when evaluating permit applications, administering grant money and holding violators accountable.

Department officials say they hope to build trust among and improve communication with state residents, especially in areas where people historically have had little control over environmental decisions.

The term environmental injustice is used by advocates to describe the systemic racism and inequity that affect some poor and minority communities.

For example, decision-makers are more likely to build highways, waste storage sites, warehouses and factories near such communities.

People who live close to such facilities have increased exposure to toxic emissions and are more likely to have chronic health conditions.

Rural areas also are vulnerable to adverse effects tied to energy development and climate change.

Michael Mann, a climate scientist at the University of Pennsylvania, cited coal mining communities in rural Pennsylvania as examples of environmental justice areas.

He said they’ve seen some of the worst waterway pollution from acid mine drainage, which can be toxic to humans and wildlife. Heavy rainfall and flooding because of “human-caused warming” worsen the environmental impacts of mining, Mann said.

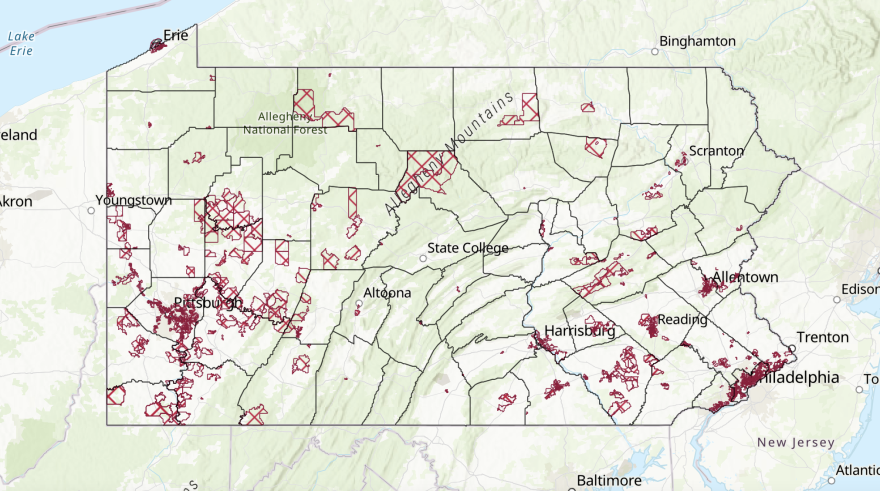

The state previously used poverty and race to define environmental justice areas. Under that definition, there were 179 areas in the state’s 48 rural counties, according to the DEP.

Under the updated policy, Pennsylvania uses 32 indicators to determine an environmental justice area — including exposure to pollution and toxic emissions, traffic volume and proximity to oil and gas wells.

It also considers race, age, income, graduation rates, unemployment and health conditions such as asthma and cancer.

The state also shifted from using U.S. Census tracts to smaller boundaries after being told that tracts were too big for the DEP’s focus.

Now the state has 1,965 environmental justice areas, with 276 in rural counties.

DEP Press Secretary Josslyn Howard said the new policy focuses more on the areas most affected by environmental harm, which lets the agency add in regions not automatically identified by the new mapping tool.

Under the new policy, when the agency reviews industrial permits for land use, it may consider a half-mile “area of concern” beyond the facility’s borders.

“The main waterways that flow into cities start in rural space. We need to be paying attention to both.”Jennifer Baka, energy geographer at the Pennsylvania State University

Jennifer Baka, an energy geographer at Penn State who serves on the commonwealth’s Environmental Justice Advisory Board, said using more comprehensive data to identify such areas will help the department understand how industrial activity affects rural communities and cities.

“The main waterways that flow into cities start in rural space,” Baka said. “We need to be paying attention to both.”

She said the new criteria better reflect how the mining, oil and gas industries, which often operate in rural communities, can influence residents’ health and the surrounding environment.

Pennsylvanians who live in the areas should expect to interact more with the agency, which said it plans to be more present in communities through increased outreach and public meetings.

Fernando Treviño, special deputy secretary for environmental justice, said the new policy aims to build trust with the public, which typically only heard from the DEP when a project was already underway or after an emergency.

The revised version also lets the DEP prioritize inspections and enforcement in environmental justice areas. So if the DEP has two facilities with the same type of violations, Treviño said environmental justice areas could be a higher priority for staff based on severity, health risks, environmental impacts, and how long a violation has existed.

Vulnerable communities also now get priority for grants, as the policy provides additional consideration for these areas when distributing public funds to address pollution and other hazards.

It also directs the department to compile an annual report to track whether these areas are receiving such funds, and to close gaps if it finds disparities.

The new policy also requires a department review of its recommendations every five years.

Despite the policy’s broader scope, environmental groups and residents have criticized it during a statewide listening tour for encouraging practices without requiring them.

Treviño said DEP is limited in its ability to enact regulations because the department isn’t a legislative body.

Legislative Democrats, who until this year were the minority party in both the state House and Senate for more than a decade, have drafted legislation that would require companies seeking permits to write an impact statement outlining possible risks for local communities and would let the DEP deny a request if it finds a proposal poses health risks.

Tougher restrictions face challenges in the Republican-controlled state Senate and possibly the House, which has a one-vote Democratic majority.