BETHLEHEM, Pa. — Residents across the Lehigh Valley can oftentimes tell when the air quality is poor, Andrea Wittchen said, and the reasons why are intuitive.

“Either we know people who have breathing problems, or we just know that the truck traffic has become ridiculously high,” said Wittchen of iSpring, a sustainability consulting agency. “ … To try to get some movement and action on this, you need to have proof that this is a problem.

“We have not, in all of these years, gathered the appropriate data to prove it, so that's what we're trying to do.”

More than a year after its launch, Lehigh Valley Breathes, a $100,000 regionwide air quality monitoring project, is still underway.

Focused on collecting data from sites across Lehigh and Northampton counties, the effort aims to monitor air quality amid emissions from the region’s prolific trucking and warehousing industries. Once the data is in hand, county officials aim to use it to inform and shape policy moving forward, as well as better position the region for grant opportunities.

While planned to be a one-year project, a slew of difficulties — from calibration and maintenance to working with residents who signed up to install monitors at their homes — has caused the regional citizen science project to take longer than expected.

"... If you want to fix a problem and fix it right, you have to understand the different aspects of the problem.”Lehigh County Executive Phil Armstrong

“I’ve found a lot of people want government to do things quickly, and it goes back centuries,” Lehigh County Executive Phil Armstrong said. “But if you want to fix a problem and fix it right, you have to understand the different aspects of the problem.”

“ … Maybe private enterprise could come in and get things done a lot quicker. Their budgets would be a lot higher. But, I think we're on pace. I'm very, very happy with what's going on.”

Air quality monitoring in the Valley

Announced in August 2023 during a news conference, the Lehigh Valley Breathes project included installing 40 PurpleAir monitors — 20 for each Lehigh and Northampton counties.

The goal is to measure PM 2.5, particles so small that they’re invisible to the naked eye, but made up of a mix of chemicals that can get deep into the lungs and can cause health problems.

PM 2.5 comes from a direct source, like construction sites and fires, or “as a result of complex reactions of chemicals such as sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides, which are pollutants emitted from power plants, industries and automobiles,” according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

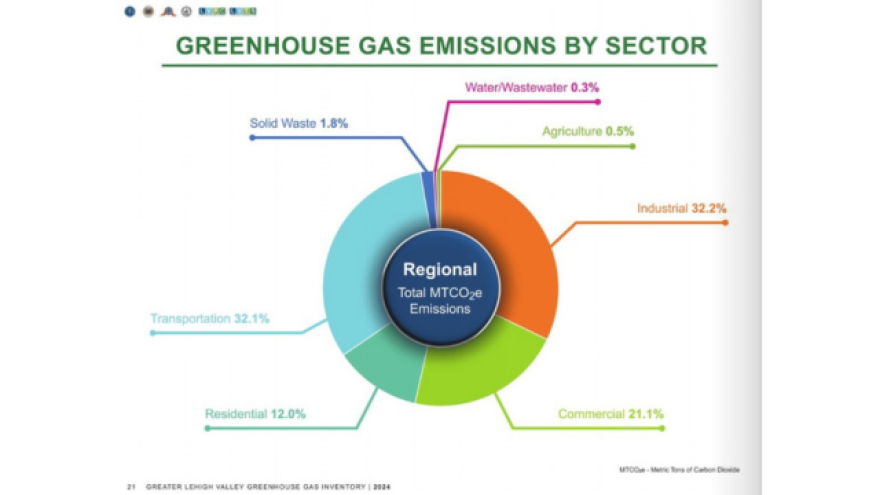

The industrial and transportation sectors are responsible for the largest share of greenhouse gas emissions across the region, according to the Lehigh Valley Planning Commission’s latest greenhouse gas assessment, at 32.3% and 32.1%, respectively.

The region already has a poor base air quality — the American Lung Association most recently graded Lehigh and Northampton counties at a “B” and “C” for particle pollution, respectively — and climate change is making it worse.

So far, the project has yielded preliminary findings in line with what officials have speculated — that air quality varies by location, with higher concentrations of PM 2.5 recorded in high-traffic areas. And, fine particle pollution in the Valley is highest near warehouses and highways.

Researchers have also found PM 2.5 pollution occurs when the wind speeds are low, and conversely, when wind speeds are high, PM 2.5 pollution levels are low.

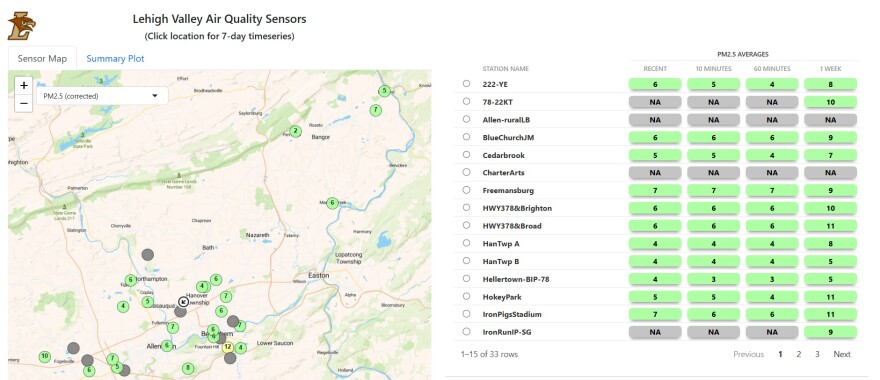

Unforeseen issues and obstacles have pushed the project back. Thirty-five monitors have so far been installed, 33 of which feed readings to the ShinyApp, the project’s dashboard.

“When we first came up with this project, our assumption was that we would start in August of ‘23 and we would have all the monitors up, hopefully, by January of ‘24, and we would have a year's worth of data around now or within a couple of months,” Wittchen said. “And then I think [Breena Holland, an associate professor of political science at Lehigh University, one of the partners on the project] is looking at maybe three or four months to do the analysis and write up the report.

“So, it would probably be the middle of next summer, if this was all going perfectly. But it's not quite.”

‘A huge amount of moving parts’

There have been setbacks, she explained, from the very start, including “a huge amount of moving parts that I think we did not anticipate.”

All the monitors used in the project had to be calibrated with two monitors already in place from the state Department of Environmental Protection in the Valley. Those two sites, in Freemansburg and East Allentown, are monitored to ensure compliance with the federal Clean Air Act.

“We used the one in Freemansburg so that the readings that we get from the little monitors, the PurpleAir monitors, are consistent with the DEP monitor,” Wittchen said. “And so every one of those monitors had to be out there for two weeks in order to acquire enough data to then do the calibration.

“ … That really slowed us down at the beginning. I think that cost us at least six months until we got everything matched up and calibrated.”

Wittchen is also “a little disappointed” in the monitors’ performance, too, she said.

The two lasers that point from the bottom of each monitor and analyze particulate matter in the air have malfunctioned, and several have needed to be replaced.

“I have ordered now, I believe it's 12 sets of new lasers that have needed to be replaced on different monitors that are out there,” she said. “And so it's a little bit disheartening, because when the lasers don't work, they go offline, and it's a chunk of data.”

When a laser goes out, the monitor stops collecting data — each monitor records the air quality every two minutes — and needs to be calibrated again.

“If you have your lasers go out and they're not working properly, you're losing days and days worth of data because of the malfunction,” she said. “It's something that a consumer can do, to replace the lasers, but we don't ask the homeowners to do that. Of course, we take care of that ourselves, but you have to have time to get out there and do it.

“That's a problem that we did not anticipate. So, then you have to either kind of extrapolate the data that you're missing or you just have a dropout. It’s challenging.”

Working with residents on the experiment has proven difficult, too. One resident who installed a monitor moved, so it had to be taken down. Another power-washed their porch and unplugged their monitor; it took them more than a month before they remembered to plug it back in.

“If this was truly run by scientists with monitors at continually controllable locations, you wouldn't have this because you have somebody watching it 24/7, and as soon as it went down, they pinpoint it, run out and do something about it,” she said. “When it's at somebody's house and it's because they power-wash their porch, it makes it a little more difficult to figure out what the problem is."

‘Actionable scientific evidence’

Monitoring air quality requires a regional approach, county executives said.

“I always put Northampton County first,” said county Executive Lamont McClure. “But the fact of the matter is, I'm in part, too, responsible for the whole Lehigh Valley. And Lehigh County, I think, looks at it the same way too, and we breathe each other's air.

“So, it makes sense. We both have warehouses. We share 22 and 78, we share the truck traffic. We share the particulate matter. It makes sense that we share the burden of trying to find out what's in the air and what we might be able to do about it in the end.”

Once the experiment is done and the report is finalized, it’ll be handed over to county officials. They’ll be responsible for taking the conclusions and applying the information when decisions need to be made or policies enacted.

“As executives, we have a responsibility to balance the interests of economic development and job creation with keeping our climate and our air quality and our water quality in keeping with good health, right?” McClure said. “We want people to have jobs, but we also want people to be healthy, so we have to balance all these interests, and it's tough, but that's why we sign up for the job to do that.”

Climate policy is driven by the federal, and to a lesser extent, state government, McClure said. Very little is driven by local government.

“However, local governments have a responsibility to fill in the gaps where the federal and state governments are falling short,” he said. “And I think, once we're done with this project, we may have actionable scientific evidence to scream from the rooftops that the federal and state governments have to take action to help us clear up our air, specifically with particulate matter, the PM 2.5 in the Lehigh Valley.”

While prefacing his answer with officials “aren’t jumping ahead” when thinking about applications for the data, Armstrong said it could be very useful when applying for grants.

Recently, the region’s planning commission was denied a grant to add trees and shrubs to the land around highway interchanges, he said. The project could have helped to improve air quality amid dense traffic emissions.

“We tried. We got turned down,” Armstrong said. “We're going to try again, and the more we have data to show the government that this is an area of major concern, and we have the data to prove it, hopefully, the more we move up on the list of getting grants to solve it.”

In addition to coordination between the two counties, participation from residents is also a key part of the project.

“The public is definitely behind us on this,” Armstrong said.

For now, monitors are still collecting data, with updates posted on the Lehigh County and Northampton County websites for the project.

“We're still chugging away,” Wittchen said. “The monitors are out there and still working.”