BETHLEHEM, Pa. — An invasive insect known for its voracious appetite that can defoliate millions of acres of forest has been an annual blight on the Lehigh Valley and the rest of Pennsylvania for decades.

But last year’s hatch of spongy moths spared the valley, and it appears this year’s will, too.

Spongy moth populations will cycle up and down according to the rhythm of the ecosystem, Muhlenberg College biology professor Marten Edwards said.

“Private landowners play a critical role in protecting Pennsylvania’s forests."State Forester Seth Cassell

They’re "influenced by the weather of a particular season and the fluctuating populations of predators and microbes,” Edwards said.

“The only time you can try to control an active outbreak on your favorite trees is during the early season in spring.

“If you are concerned about your property, now is a good time to contact a licensed arborist for advice. Once you start to see the actual damage, it’s too late to do anything about it.”

However, with 70% of all forest lands privately owned, state officials are urging property owners to survey their land and prepare treatment options if needed.

“Private landowners play a critical role in protecting Pennsylvania’s forests,” State Forester Seth Cassell said in a news release.

“Early action against spongy moth caterpillars can help prevent widespread tree loss.”

'Trying to control them'

For treatment, the DCNR uses Bacillus thuringiensis kurstaki, or Btk, an insecticide, and Mimic, an insect growth regulator. Both can be deployed via airplane.

Last year, between the DCNR and the Game Commission, 347,000 acres of state forest and park lands were treated, officials said.

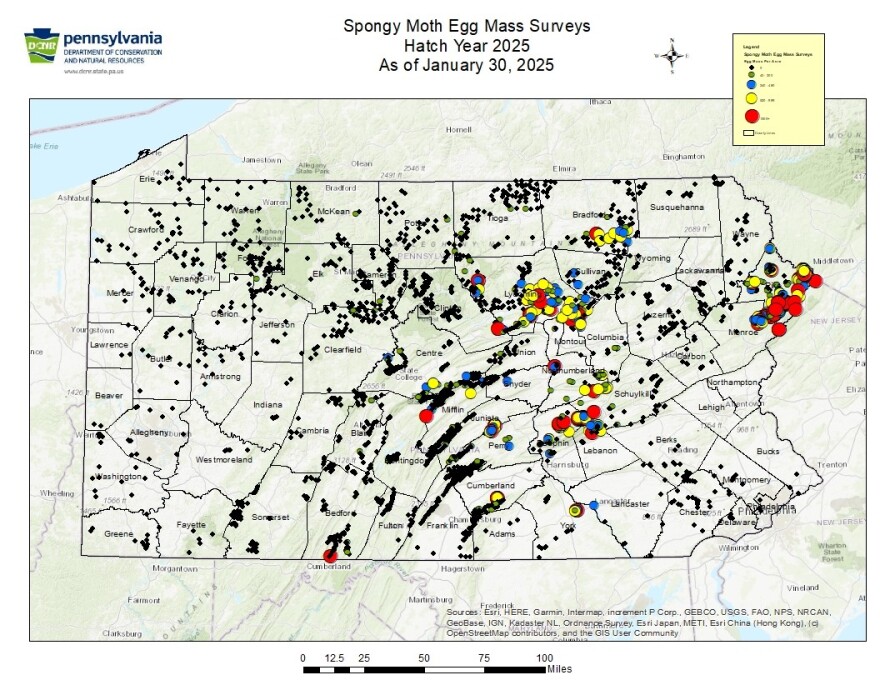

This year, the DCNR plans to treat about 75,000 acres, primarily in northeastern and central Pennsylvania, and the Game Commission plans to treat about 38,000 acres.

This year’s spray program runs from the end of April through May, DCNR Press Secretary Wesley Robinson said.

"Weather, leaf development and caterpillar development may shift that a little, but in general, the spray program is during the same time every year," Robinson said.

The most recent egg mass surveys show concentrations in Pike, Lycoming, Dauphin and Lebanon counties.

“Trying to ‘control’ them with broad-spectrum chemical insecticides is counterproductive since that also kills their natural enemies that will drive the population down the next year — free of charge,” Edwards said.

“When professional foresters, such as those with the state Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, determine that control is helpful, they use highly targeted methods that have a minimal impact on the helpful insects.”

Here is LehighValleyNews.com’s interview with Edwards. Some answers were edited for style and clarity.

Q: What are spongy moths?

A: "Spongy moths belong to a large family of moths called the Tussock Moths. They are particularly destructive (in fact their scientific name, Lymantria dispar, means Destroyer) because they can reach large population sizes rapidly and feed on many different species of trees."

Q: Where did they come from?

A: "They were originally imported from Europe to the Boston area in 1869 by a person who dabbled in entomology and thought it would be a good idea to cross this species with silk moths to make a more disease-resistant silk moth. It was a terrible idea that could not work since they are different families of moths that can't possibly interbreed. They escaped from his garden and had already invaded forests in Massachusetts by the 1880s. They started to become a serious problem in Pennsylvania in the 1970s."

Q: What does their life cycle look like?

A: "Like other moth species, they have an egg, caterpillar, pupa, and adult stage. They only get to squeeze in one generation per year. The females lay eggs in brownish-grey masses that look like a sponge — thus the name.

"The eggs generally hatch in May, the tiny caterpillars crawl up the tree to feed on the leaves. When they are very small, they can make little parachutes from a strand of silk, and use this to hitch a ride on the wind and invade new places, sometimes even a mile away.

"The bristly black caterpillars with blue and red spots on their back will continue growing to their final size of a bit more than two inches. They will then spend a few weeks as a pupa and emerge as adults in late July and August.

"The adults don't eat. Bizarrely, the female adults are flightless, and they attract male moths to them by releasing a pheromone — 'Don't call us, we'll call you.' After mating, the females deposit spongy masses containing as many as 800 eggs on tree trunks. It takes about 9 ½ months for the new generation of caterpillars to emerge from their protective eggshells the next year in May."

Q: Are there particular species or trees or shrubs that spongy moths prefer?

A: "Some of their favorite trees are oak, apple, basswood, willow and birch trees. In heavy infestations, the spongy moth will feed on some evergreen species including pine, spruce and hemlock. They do not like dogwood, sycamore, tulip, redbud and other trees."

Q: How destructive can they be?

A: "It depends on the tree and the level of infestation. They can completely defoliate trees, but that does not always kill them — they often leaf out again later in the summer after the caterpillars have finished feeding. Many trees can bounce back after being defoliated as long as they are not stressed by a drought or attacked by a different insect hitting them when they are already down.

"Hiking in a forest during a major infestation is an eerie experience, as all of the falling poop [frass] can make it feel like it is raining. Although it can seem like the end of the world, otherwise healthy deciduous trees can usually survive a few seasons of defoliation."

Q: Do they have any predators in the Valley?

A: "Yes, they have lots of predators, including white-footed mice [the ones that are famous as hosts for the bacteria that cause Lyme disease] and other rodents like shrews and squirrels. Rodents generally feed on the pupa stage, so they won’t stop active infestation but will reduce the number of adults that can lay eggs.

"The caterpillars are eaten by several species of birds. They are also killed by parasitoid wasps and flies, insect-killing fungi and viruses that specifically infect the caterpillars."

Q: Where would residents find them in the Valley?

A: "They are not hard to find. They are present in any wooded area. Last summer, they were happily munching away on the sycamore tree in my backyard in the West End of Allentown, but they didn’t defoliate the tree. However, in non-outbreak years, they may be rare and hard to find."

Q: Has the Valley seen damage from spongy moths?

A: "Definitely. The population goes up and down in cycles that last about 10 years between “outbreaks” that will last a few years. As the number of moths increases, so does the abundance of predators and microbes that kill them, which forces the population back down.

"The last outbreak in Pennsylvania forests, according to the PA Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, was from 2021 to 2024. It is expected that the population of natural predators and pathogens will have risen enough during that time to bring the infestation back under control for the next few years."

Q: In the past few years, spongy moths seem to have spared the Valley — do we know why?

A: "Maybe we’ve just been lucky. The last major local infestation I remember was in 2015, and by 2016 it had already started to die down. These fluctuations are normal. The time-honored truism 'this too, shall pass' applies to spongy moths."

Q: Have there been any new developments in spongy moth prevention or treatment?

A: "The USDA has been doing some very interesting and important work documenting the infections of spongy moths with viruses and fungi. This research may seem obscure, but it has an amazing return on investment considering the $3.2 billion annual impact these moths have in North America alone."