GERMANSVILLE, Pa. — There’s a raptor superhighway along Blue Mountain, right in the Lehigh Valley’s back yard.

- The Lehigh Gap Nature Center's annual raptor count started Aug. 15 and runs through November

- Volunteers are needed to record the species and number of raptors migrating

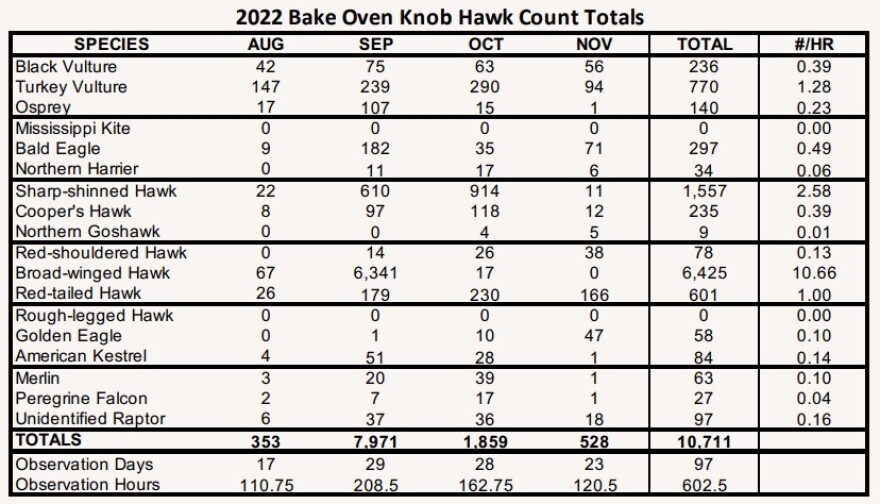

- Data collected is shared and used for global conservation efforts

“It's basically a point where these birds concentrate in their migration,” said Chad Schwartz, executive director of the Lehigh Gap Nature Center. “And there's really two reasons for that. The first is that it is kind of like a road map … but at the same time, these mountains are really good at generating winds to help the bird save energy.

“It's basically a combination of helping them navigate but also powering their flight. That's why [the Kittatinny Ridge] is so important.”

Thousands of raptors — from vultures, eagles and kites to hawks, kestrelsand falcons — are expected to make their annual trek through the region over the next three months, and researchers are ready. A team of observers and counters from the Lehigh Gap Nature Center on Tuesday began this year’s Bake Oven Knob Autumn Hawk Watch, carrying on a more than 60-year tradition of conservation research.

About a dozen people attended an informational Zoom session earlier this month to learn about ways they can get involved, officials said, but more volunteers are needed to keep it going.

"We're in the process of trying to rebuild and recruiting new folks to join the team."Chad Schwartz, executive director of the Lehigh Gap Nature Center

“We've had some volunteers who've been involved since the [19]60s, actually,” Schwartz said. “But as they've gotten older, it is more difficult for them to access the site up there. We're in the process of trying to rebuild and recruiting new folks to join the team.”

Why count raptors?

Annual counts help researchers track the status of raptor populations, Schwartz said.

“It was actually data from Hawk Mountain, and elsewhere, that alerted scientists that something was wrong during the DDT era,” he said. “They saw a decline in certain birds of prey like bald eagles, peregrine falcons and knew something was wrong, but they didn't know what was wrong.”

DDT, or dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, is an insecticide, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. It was banned in 1972 across the U.S. “for its adverse environmental effects, such as those to wildlife, as well as its potential human health risks,” according to the agency.

“They figured out that it was DDT, which actually affected the way that these birds lay their eggs,” Schwartz said. “ … They wouldn't have figured any of that out if they hadn't been keeping track of the bird populations prior to that point.”

The count is only a decade older than the DDT ban, started by Donald S. Heintzelman at Bake Oven Knob during a time when conversations moved from exterminating raptors — the common belief being that they were nuisance birds — to protecting them.

“It all started actually in 1934, when Hawk Mountain Sanctuary was established — that's when basically hawk watching was established as a science and a hobby, too,” Schwartz saud. “Prior to that point, a lot of these birds were considered vermin and many of them were actually hunted with permission from the state of Pennsylvania.”

More than a century ago, raptors were often viewed as villainous predators. In one early film, Thomas Edison even used “special effects” to show some sort of raptor carrying off a baby.

“That kind of represents how these birds were viewed back then,” Schwartz said. “They were considered vermin — that was the official term used to describe them.”

The commonwealth’s Scalp Act of 1885 “placed a 50-cent bounty on weasels, minks, gray and red foxes, and all hawks and owls, excepting saw-whet, screech and barn owls. It also provided a 20-cent fee to the local notary or justice who recorded a bounty affidavit,” according to the state Game Commission.

What are you researching? Today, I'm on Pennsylvania's Scalp Act of 1885.

— Molly Bilinski, artisanal sentence crafter (@MollyBilinski) August 15, 2023

(📸 from "A Brief History of Raptor Conservation in North America" by Keith L. Bildstein) pic.twitter.com/mIk5IQU8ed

Proponents argued the slaughter was worth saving chickens and other agricultural raptor prey — it wasn’t.

Today it stands as the height of senseless slaughter and wasted tax money. In about 18 months, about $90,000 — $2.2 million today — had been spent and 128,571 targeted animals, mostly hawks and owls, were killed."Pennsylvania Game News," Feb. 2020

“Today it stands as the height of senseless slaughter and wasted tax money,” according to a Feb. 2020 edition of "Pennsylvania Game News," posted on the commission's website. “In about 18 months, about $90,000 — $2.2 million today — had been spent and 128,571 targeted animals, mostly hawks and owls, were killed.”

In recent years, bald eagle and peregrine falcon populations have shown strong growth, but researchers are keeping watch for other raptors that are threatened by habitat loss.

“The ones that we're more concerned about are the grassland-dependent birds, and the ones that we count are American kestrels and northern harriers,” he said. “They're the two species that depend on grasslands for their prey, and a loss of grasslands across North America is impacting their population.”

Data from the count is then reported to the Hawk Migration Association of North America to help inform researchers focused on global conservation efforts.

‘What makes the hawk watch really special’

Schwartz has been involved in the count for almost a decade. While he’s experienced more than a few memorable moments, he recalled one morning when he saw hundreds of broad-winged hawks move on from their overnight roosts.

“When the sun rises, they rise up from the trees in groups of hundreds and then fly along the ridge to continue their migration,” he said. “I happened to be there probably 7:30 or eight in the morning one [day in] September and I actually saw that happen … That was pretty special — seeing that happen.”

Experiencing a mass raptor migration first-hand can be a powerful experience, but there are some days during the three-month count when cloudy skies obscure the view or there are just no birds to record.

“The other aspect of this all is the people you meet, though, and that's really what makes the hawk watch really special,” Schwartz said.

When the count lags, volunteers still have gorgeous views and great conversations, he said.

“I met some really amazing and very interesting people up there and I'm sure any of our volunteers will say the same thing,” he said. “Especially being on the Appalachian Trail, you get through-hikers who are doing the entire trail, you get a lot of visitors from all over the area, besides New York City, Philadelphia and other places.

“You just never know who's gonna stop by the hawk watch.”

Interested in volunteering?

Although the count has already started, residents can still volunteer – and there’s more to it than counting birds.

Generally, volunteers start out as observers, who support the counters, taking a season or two to acquaint themselves with the task, Schwartz said. Once they’re comfortable, they can take on counting, which includes recording hourly counts and the weather, as well as visitor data that’s reported back to the center.

While observers can volunteer for as few or as many hours as they please, counters are needed, especially on the weekends.

“That is really where we could use the most support, because there are some shifts throughout the season every year where we don't have coverage,” Schwartz said, “That means less information that we have for our research, but we understand we're relying on volunteers and sometimes that's just how it goes.”

But volunteers are welcome to join “at any point in the season,” he said.

“If somebody's interested in volunteering, we can certainly work with them to get them caught up,” he said.

Interested in volunteering at the Bake Oven Knob Hawk Watch? Email mail@lgnc.org.