BETHLEHEM, Pa. — Challenges for beekeepers are many and varied, Ken Szydlow said, including threats from weather, pesticides and disease.

- Native pollinators, including Pennsylvania's more than 400 species of bees, are under threat due to habitat loss, disease and pesticide use

- Honey bees are a non-native species

- World Bee Day is marked May 20

“A sign of success is how many hives make it through the winter,” said Szydlow, who currently maintains 12 hives. “In Pennsylvania, over the last couple of years, I think backyard beekeepers are lucky if half of their hives make it through the winter because of major challenges.

“There are colony disorders, diseases that ravage bees and the effects really take place during the winter.”

Honey bees make up only a small segment of the Lehigh Valley’s pollinator population, but all bees are struggling, experts say. While researchers have identified more than 400 species across the state, external forces, like those Szydlow identified, as well as habitat loss, have threatened local bee populations.

But, scientists and beekeepers alike said there’s plenty local residents can do to encourage local pollinators, from supporting habitats to planting native flowers.

Helping to bolster bee populations was his catalyst to begin beekeeping, Szydlow said. He started six years ago, and has a 15-hive goal.

Before World War II, there were more than 4.5 million backyard beekeepers across the U.S., he said. Today, there’s less than 2 million.

“If you think about it, pollinators, not just honey bees, but all pollinators, are so invaluable when it comes to maintaining, growing crops and we depend on pollinators,” he said. “So it just seemed like it was a neat thing to do to try to make a difference in expanding or helping the declining pollinator population.”

"If you think about it, pollinators, not just honey bees, but all pollinators, are so invaluable when it comes to maintaining, growing crops and we depend on pollinators."Ken Szydlow, beekeeper

‘People needed wax’

Honey bees aren’t native to the U.S. — they were brought over by European colonists.

While there are myths that the insects were used for pollinating apple trees or for their honey, Marten Edwards, a professor and chair of Muhlenberg College's biology department, said they were used for a much more practical purpose.

“The fascinating thing about honey bees is that they were introduced mostly because people needed wax,” said Edwards, noting that colonists obviously didn’t have access to electric lights. “They were not brought over as pollinators, and honey was a wonderful byproduct that they made.”

Bees have been moved across the world and are used today for a variety of tasks and products, from pollination to honey. About a decade ago, the United Nations approved a proposal to mark May 20 as World Bee Day to raise awareness of the importance of pollinators. It’s acknowledged each year on the birthday of Anton Janša, a pioneer of the beekeeping field born in 1734 in Slovenia.

“Nearly 90% of the world’s wild flowering plant species depend entirely, or at least in part, on animal pollination, along with more than 75% of the world’s food crops and 35% of global agricultural land,” according to the organization’s website. “Not only do pollinators contribute directly to food security, but they are key to conserving biodiversity.”

Currently, extinction rates in pollinator species, which includes bees but also butterflies, bats and hummingbirds, are 100 to 1,000 times higher than normal due to human impacts, UN officials said.

For decades, bee population counts have been concerning, Edwards said, but declines have seemed to plateaued.

“In the last 10 years or so it's leveled off — lower than it was before the 80s but, with honey bees, it's not continuing to plummet,” he said. “As a crop, it's fairly stable. Humans are good at taking care of our crops.”

Continuing threats to honey bees include mites, diseases and colony collapses.

“Beekeepers will go out to the beehive and nobody's home,” he said. “So this is a problem and it continues to today, but it's not an increasing problem. It's a steady problem.

“It's something that if you are a beekeeper, you're aware that this is something that is part of the reality of keeping bees.”

‘What makes a bee a bee’

Robyn Underwood, a Penn State Extension apiculture educator, said few people actually know how to identify a honey bee.

“What makes a bee a bee is that it is hairy,” Underwood said. “Literally they have branched hairs on their body, and those hairs have a static electric charge that helps them to collect pollen.

“The pollen is powdery and it will stick to the hairs kind of passively. So that's what makes a bee.”

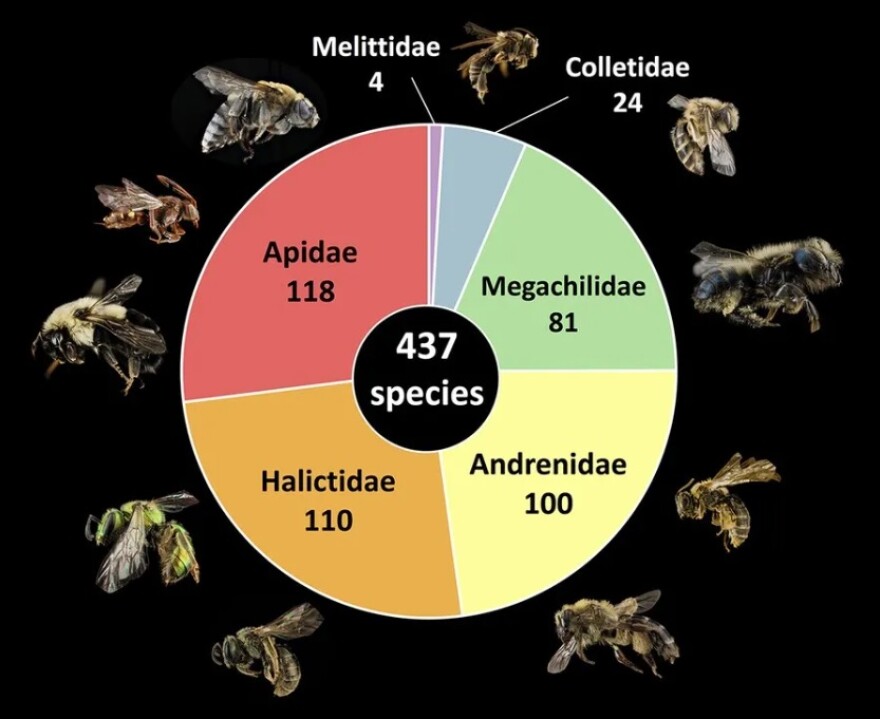

There are at least 437 species of bees that contribute to pollinating the commonwealth’s natural areas, gardens, and agricultural crops, according to Penn State Extension researchers. Most nest in the ground and are solitary insects.

Some of the most important bees in the Lehigh Valley are those residents might not even notice, “because they don’t bother us,” Edwards said.

“They almost never sting and they go about their lives, almost completely unnoticed,” he said. “People don't even notice that they're bees because they're small. If I point them out, people say ‘That's a bee? I thought it was a fly.’”

It’s these bees — the native pollinators - that are struggling the most, researchers said.

“They're critical to our environment,” Underwood explained. “There's a lot of very specialized relationships between one type of bee and one type of plant. And if we want to preserve biodiversity of plants, we should preserve biodiversity of bees as well.”

‘A calming experience’

Marina Falzone, president of the Lehigh University Beekeeping Club, said she can’t articulate the feeling she gets when working with bees.

“It is really a calming experience, and I really can't describe what being in the hive is like,” she said. “It's just a really great experience to kind of get involved with a really important initiative, in my opinion.”

Falzone started working with bees in high school, and this year took on the officer’s role in the club. A sophomore, she’s studying mechanical engineering and finance.

While still rebuilding the club after the pandemic, there is one hive at the university’s Goodman Campus, near community gardens, she said.

“We're kind of in the rebuilding process. I've been reaching out to a lot of other, senior beekeepers in the area to kind of learn more myself but also gain a little bit of support as we're bringing the club back to its full capacity,” Falzone said. “We're hoping if we can make it to the winter, I would love to add a second one in the spring.”

But Lehigh Valley residents don’t necessarily need to visit a hive to spot some honey bees - it’s the time of year in the Valley when they can be spotted massing before looking for new homes.

John Gowin, president of the Lehigh Valley Beekeepers Association, said during the spring and early summer months, honey bees tend to swarm, a method of reproduction.

“A cluster of 10,000 to 15,000 bees hanging on a tree can be an impressive site,” Gowin said. “It is important to remember these bees are in search of a new home, and are generally docile if left alone.

“They generally will stay for a couple hours to a day or two and then move on to an empty cavity and create a new home.”

The LVBA has a list on its website of beekeepers who will come and collect swarms and provide them a place to thrive, Gowin said.

‘Feed the bees’

Underwood remembers growing up in the Reading area and seeing weeds line the roads and highways.

“These days, I see corn, then the road or corn, a tiny strip of mowed grass and the road,” she said. “This precision agriculture has taken away all those little snacks for the bees, like all the little weedy edges and things where they couldn't quite get and we're so good at getting rid of those weeds that we haven't realized what they were actually doing for the bees.

“ … I doubt I can convince a farmer to allow the weeds. So we have to kind of make up for that.”

For residents, that means leaving some unused yard areas to grow weeds and wildflowers, or planting native flowers, experts said.

“I say, plant lots of flowers that make lots of nectar and pollen, and don't spray them with pesticides,” Underwood said. “If you want to support honey bees and beekeepers, buying local honey is a great thing to do, but becoming a beekeeper yourself is not what we promote for saving the bees.

“We want people to plant lots of diverse flowers, not use pesticides on them. That's the most important thing — feed the bees.”

Over the last few years, Szydlow hasn’t used weedkiller on his lawn, about an acre.

“As a result, I've noticed I have a lot more birds in my backyard,” he said. “I have a lot more bees of all types. I've also had more frogs and snakes and rabbits. So, I have definitely noticed an increase, an uptick in the wildlife in my backyard, which I enjoy.”