BETHLEHEM, Pa. — St. Luke's University Health Network on Friday launched an email helpline for residents with questions about bird flu.

“While we have not had any known human cases of avian influenza in our local area, Pennsylvania or New Jersey, we have learned from past novel infectious diseases that it is prudent to be proactive in our approach,” Dr. Jeffrey Jahre, an infectious disease specialist at St. Luke’s, said in a news release.

Officials at St. Luke’s, one of the Valley’s two major health networks, are preparing for potential human cases of bird flu across the region.

At this point, there is no cause for alarm. But taking some preliminary steps now will help us to assess our current situation and prepare for possible future developments.Dr. Jeffrey Jahre, an infectious disease specialist at St. Luke’s University Health Network

Strategies include working closely with the network’s lab and clinical providers, sharing information and offering assistance with regional poultry professionals and engaging with residents.

“We are proud of our leadership role and continue to take our responsibility to our community very seriously,” Jahre said. “We learned during COVID that we cannot wait for government agencies to ride in and save the day.”

Valley-area residents can email questions to birdfluquestions@sluhn.org.

“At this point, there is no cause for alarm,” Jahre said. “But taking some preliminary steps now will help us to assess our current situation and prepare for possible future developments.”

Bird flu in the Valley

Over the past several weeks, avian flu has grown to be a more and more pressing issue in the Valley.

An influenza type A virus, bird flu, also called HPAI, or highly pathogenic avian influenza commonly referred to as bird flu or H5N1, is highly contagious and often fatal in birds.

As the virus spreads, it’s impacted the region’s wild animals and domestic poultry, including about 5,000 migratory snow geese and a 50,000-bird egg-laying chicken flock on a commercial farm.

The former, identified in Lehigh County late last month, was the first avian case on a domestic poultry farm this year in Pennsylvania.

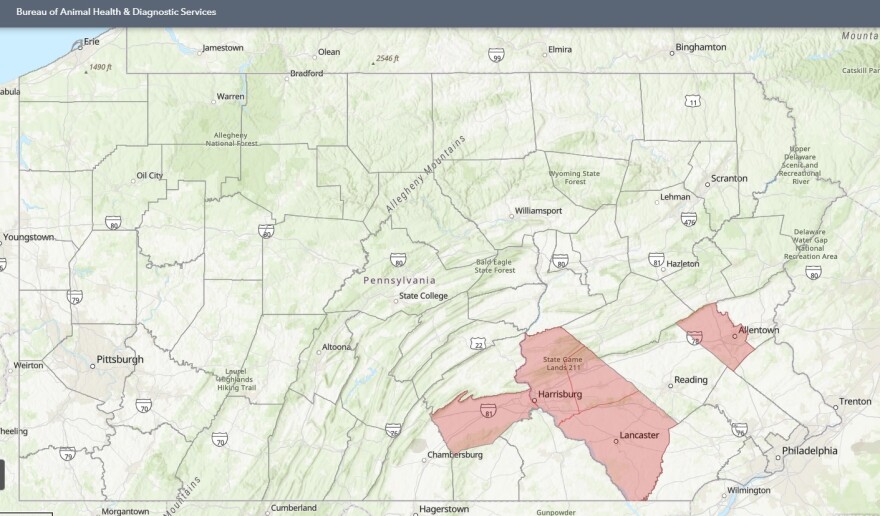

Since then, presumed positives have been found on farms in Cumberland, Dauphin, Lancaster and Lebanon counties, based on the presence of the virus in initial samples and rapid deaths among birds.

“Pennsylvania continues to take swift, aggressive action to protect our farmers and our dairy and poultry industries from avian influenza,” said state Agriculture Secretary Russell Redding, in a Thursday news release.

Each presumed positive farm has been quarantined, officials said.

All commercial poultry facilities within 6.2 miles (10 km), and dairy farms within 1.8 miles (3 km) of infected flocks are subject to testing requirements and restrictions.

A developing wave

The most recent wave follows other instances of bird flu in Lehigh and Northampton counties since the initial outbreak in 2022.

The virus jumped from birds to mammals in the Valley in May 2023, when a red fox became the first mammal in the region infected. In early March last year, a bald eagle collected in Monroe County also tested positive.

In November, state agriculture officials mandated Pennsylvania dairies to bulk test for avian influenza.

While no cases of the virus have been reported in Pennsylvania cattle, other states have seen a marked uptick in cases since the first outbreak in cattle was reported in March.

Last month, state Game Commission officials said about 200 snow geese were found dead in Lower Nazareth Township and Upper Macungie Township from suspected bird flu.

That number quickly swelled to 5,000.

Less than a week later, the Lehigh Valley Zoo announced the barnyard birds, waterfowl and penguins were taken off exhibit due to concerns about the virus.

It’s at least the second time since 2022 the zoo has taken birds off exhibit due to the avian flu.

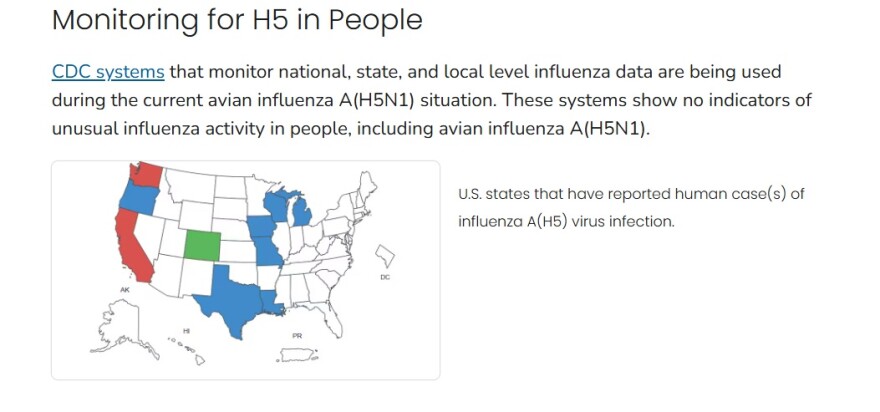

The United States saw the first human death from avian flu in January — a person in Louisiana, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Even with that death, health professionals, both locally and nationally, say the risk to people is low.

Frequently asked questions

Here are St. Luke’s bird flu FAQ:

What is avian influenza?

Avian influenza (“avian flu” or “bird flu”) is a type of influenza that primarily infects birds but can sometimes cause infection in mammals like cows, and rarely humans.

How widespread is avian flu?

- Wild Birds

Avian flu has been found worldwide in wild birds including waterfowl, gulls, and shorebirds since 2022. There has been an uptick in the number of wild birds infected in both the Lehigh Valley and New Jersey in the past month.

- Poultry and Cattle

Avian flu has also been causing outbreaks in domestic poultry and dairy cattle in some areas of the US. Pennsylvania had its first case of avian flu in a commercial chicken flock in Lehigh County this month. So far, there have been no cases of avian flu in cattle in Pennsylvania, and no cases in poultry or cattle in New Jersey.

- Cats

Since 2024 dozens of cats have also contracted avian flu, including barn and feral cats, indoor cats, and big cats in zoos and in the wild (e.g., mountain lions, tigers, leopards, and bobcats). Infection is thought to be largely related to exposure to unpasteurized milk and raw or undercooked meat in food.

- Humans

There have been 67 confirmed human cases of avian flu in the United States since 2024, including one death. There have been no reported human cases of avian flu in New Jersey or Pennsylvania. Ninety-six percent of cases in the United States have been linked to animal exposures. There have been no documented cases of human-to-human spread.

What are the symptoms of avian flu?

Most human cases of avian flu in the United States have been mild. Symptoms have included eye redness and irritation (this has been the predominant symptom), mild fever, cough, sore throat, runny or stuffy nose, muscle or body aches, headaches and fatigue.

How is avian flu spread?

Almost all cases of avian flu in humans have been caused by close contact with infected live or dead birds. There have been rare cases of spread to humans from infected mammals, like cows. So far, there has been no known human-to-human spread of avian flu. The avian flu virus has also been detected in unpasteurized (raw) cow’s milk. While there have been no cases of human avian flu directly linked to raw milk, it could still be a potential source of infection.

What is the incubation period of avian flu?

The time from when a person is exposed to avian flu to when they develop symptoms is about three days but can range from two to seven days. Eye symptoms such as redness and irritation can be one of the earliest symptoms, occurring one to two days after exposure.

How do we test for avian flu?

Patients with avian flu will test positive for influenza with our current PCR tests. Further specialized testing could then be performed to confirm the avian flu strain in people with risk factors for exposure.

How is avian flu treated?

Our current medications for influenza (i.e., Tamiflu) have activity against avian flu.

Does the annual influenza vaccine protect against avian flu?

No, but there is an approved avian flu vaccine for humans that is being held in the national stockpile in case it would be needed.

How can individuals avoid becoming infected with avian flu?

- The most important prevention measure is to avoid direct contact with sick or dead wild birds, poultry and other animals, or anything that may have been contaminated by them.

- Hunters who handle wild birds should dress game birds in the field when possible and wear appropriate protection including gloves, an N95 or surgical mask and eye protection.

- Backyard poultry and livestock owners should take measures to avoid avian flu infection in their animals following USDA guidelines. They should also follow good hand hygiene and wear appropriate protection when caring for their animals.

- Visitors to livestock fairs and shows should follow good hand hygiene and wear appropriate protection when in close contact with animals or consider avoiding these events altogether.

- Pet owners should avoid feeding unpasteurized milk or raw meat to their pets and should always wash their hands thoroughly after handling any pet food.

Go to the CDC’s website for more information about maintaining safety around potentially infected domestic animals and wildlife.

Is it safe to eat chicken and eggs?

It is safe to eat chicken and eggs if they are thoroughly cooked. Hands and surfaces that come in contact with raw chicken or eggs should be thoroughly cleaned.

Is it safe to consume raw milk?

Avian flu has been detected in unpasteurized (raw) milk. While there have been no cases of human avian flu directly linked to raw milk or raw milk products like soft cheese, ice cream and yogurt, they can still pose a risk for avian flu as well as other serious infections. Pasteurization is the safest way to kill bacteria and viruses like avian flu in milk.

Overall, how concerned should I be about avian flu?

The risk from avian flu to the general public at this point remains low, but public health and agricultural officials continue to monitor the situation. We will continue to provide updates as we learn more information.