- A report released in late August by Lehigh County Controller Mark Pinsley calls for a review of how all cases of child abuse are handled

- The controversy mirrors others across the country

- Many experts in different fields have different takes on how the system should be reformed and what to do about such allegations

ALLENTOWN, Pa. — For weeks, stories about children being taken from Lehigh Valley parents at the word of only one doctor have circulated in the news and social media.

The local advocacy came as a result of a report released in late August by Lehigh County Controller Mark Pinsley, who is running for re-election this year against Republican Robert Smith Jr.

Pinsley’s report alleges “systemic overdiagnosis” of medical child abuse in the county.

Formerly known as Munchausen syndrome by proxy, the condition happens when a caregiver deliberately fabricates or induces an illness in someone under his or her care, often to gain attention or sympathy.

“All of these guys are being trained in the same way and they're sharing the same tactics. They have gotten into the role of being an investigator where they really don't have any place.”Lehigh County Controller Mark Pinsley

Pinsley has worked with the Lehigh Valley’s Parents’ Medical Rights Group, which was formed in response to alleged false accusations of child abuse by Lehigh Valley Health Network.

Pinsley and the group have called for an independent investigation into Lehigh County’s Children and Youth Services, the agency that handles local cases of suspected abuse, and more oversight into the work of local child abuse pediatricians, the doctors that review medical records for signs of potential abuse.

However, the Lehigh Valley is not the only region where the system of investigating child abuse has been criticized.

There have been several recent highly publicized cases of alleged false accusations, including one featured in this year's 2023 Nextflix documentary “Take Care of Maya” and about a dozen featured in the 2019 NBC Universal series “Do No Harm.”

Some, such as Pinsley, argue that the prevalence of these cases shows that the practice of child abuse pediatrics is flawed, giving child abuse pediatricians too much power when they are primed to see abuse in places it isn’t.

“All of these guys are being trained in the same way and they're sharing the same tactics,” Pinsley said. “They have gotten into the role of being an investigator where they really don't have any place.”

But others say many people contribute to the decision about whether a child should be removed from their caregivers, and the field of child abuse pediatrics has come under unnecessary fire.

“I think there’s been a lot of bad press on what’s generally a decent field,” said Howard Dubowitz, director of the Center for Families at the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore.

“We're trying hard to figure out what happened,” Dubowitz, a board-certified child abuse pediatrician, said.

“We're careful to consider all the possibilities. This is very much part of the job description, that we not jump to any conclusion, especially recognizing the enormous ramifications for the child and family."

Pinsley’s report and its response

Pinsley’s report alleges “systemic overdiagnosis” of medical child abuse in the county.

“The reader must understand that our investigation did not reveal a few anomalies attributable to human error. Instead, our analysis showed statistical anomalies suggesting a pattern that requires further investigation.”Report compiled by Lehigh County Controller Mark Pinsley

“The reader must understand that our investigation did not reveal a few anomalies attributable to human error,” the report states. “Instead, our analysis showed statistical anomalies suggesting a pattern that requires further investigation.”

Pinsley said that while his report focuses on medical child abuse, he has become concerned about how physical abuse is investigated, as well.

In the month since the report was released, parent advocates have protested in front of LVHN hospitals.

They have recounted similar experiences at county commissioner meetings: they took their child to a Lehigh Valley Health Network hospital for a medical issue and left the hospital without their child.

Those parents were told that a member of Lehigh County’s John Van Brakle Child Advocacy Center, or CAC, had evaluated their case and suspected them of abuse.

In many instances brought forward, the parents said their cases later were dropped for lack of evidence.

Many of the members of the Parents Medical Rights Group have called for LVHN to fire child abuse pediatrician Dr. Debra Esenerio-Jenssen, who is the head of the county’s CAC.

They cite her legal troubles in other states, her demeanor in handling the cases and the amount of power her word carries in child abuse cases.

LVHN has since removed Esenerio-Jenssen as the head of the department, though advocates allege she still is handling cases of child abuse.

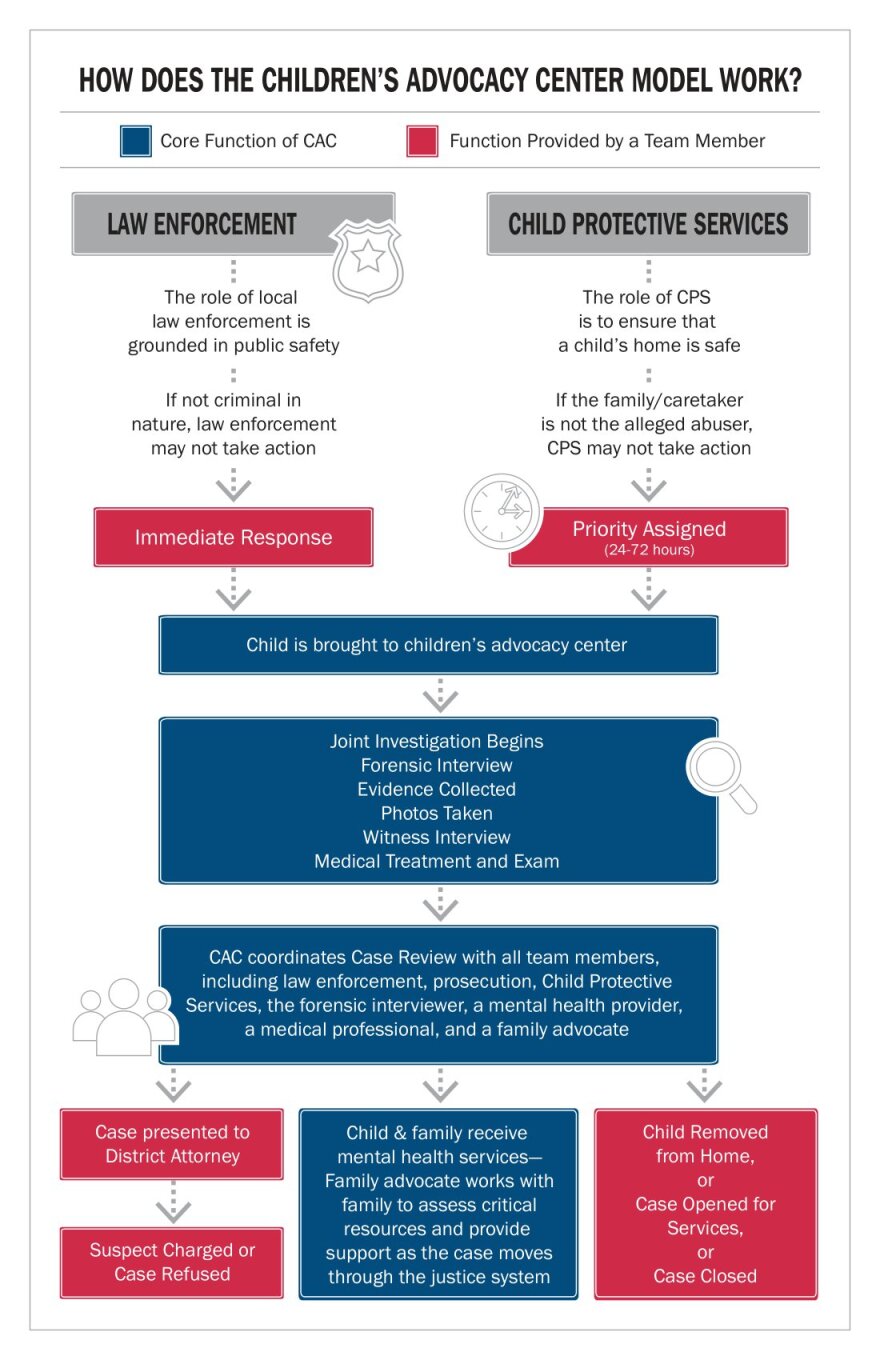

How CACs works

LVHN and Children and Youth Services declined several requests for an interview about how the county’s CAC functions. LVHN representatives instead referred to the CAC Family Booklet.

A biannual report from the county District Attorney’s office from 2021 has an article about the county’s CAC. It says it has 50 members as part of its multi-disciplinary team that includes the district attorney’s office, the Lehigh County Office of Children and Youth, Allentown Police, the LVHN Child Protection Team, a forensic interviewer and a family advocate.

The CAC’s website says it follows the National Children’s Alliance model for responding to child abuse allegations.

According to the organization’s website, those centers centralize the response to child abuse allegations by having one place for interviews, therapy, medical exams, case management and other services.

“Without a CAC, the child may end up having to tell the worst story of his or her life over and over again, to doctors, cops, lawyers, therapists, investigators, judges and others,” the website reads.

“They may have to talk about that traumatic experience in a police station where they think they might be in trouble or may be asked the wrong questions by a well-meaning teacher or other adult that could hurt the case against the abuser.”

Child abuse pediatricians such as Essernio-Jenssen work within child advocacy centers to give medical evaluations to children who are suspected to have been abused.

Child abuse pediatrics is a subspeciality of the American Board of Pediatrics that requires additional certification through a fellowship and an exam.

In cases of suspected medical child abuse, such pediatricians often look through medical records to see if there are any signs of deception or fabrication and perform physical examinations on the child.

There are several published guidelines for how child abuse pediatricians should conduct their analysis work with others within a CAC, but specific practices vary.

Yale University researchers published a specific outline of practices to answer questions raised by concerned members of the public and the media.

The practices listed in this article do not reflect the parents' retellings.

1-s2.0-S0145213420304476-main by Mariella Miller on Scribd

Child abuse pediatricians under fire

In many of the publicized cases of parents saying they were falsely accused of child abuse, the field of child abuse pediatrics has come under fire — with many complaints mirroring those of the Lehigh County parent advocates.

For example, in the case featured in “Take Care of Maya,” child abuse pediatrician Dr. Sally Smith was accused of having an unreasonable amount of influence in the court’s decision to remove Maya from her parent’s care.

She also was criticized for her unwillingness to question her original assessment when other information came to light.

Dr. Eli Newburger helped found the Child Protection Program at Boston Children's Hospital in 1970 and served as its medical director for several decades. He now runs a consultation practice for cases “in which families have been grievously harmed by the misdiagnosis of child abuse.”

Newburger said he thinks the field of child abuse pediatrics has been flawed since its conception. He was at the meeting convened by the American Academy of Pediatrics in the late 1990s to discuss whether to create the subspecialty.

“I objected to those efforts because of my concern that if pediatricians were identified as specialized in this field, they would be appointed… as the people who would be called in to say, ‘Thumbs up or thumbs down, is this child abuse?’” Newburger said.

“I pointed out then, and still believe now, that the new specialty would be better characterized as forensic, in which the physician's role as an expert would be to guide and inform decision-makers in the field that dealt with criminal and civil allegations.”

Newberger said his perspective is “distinctly uncommon” in the field. He said he gets about one consultation request a week from across the country, and his consultation roster is currently full.

System still works

But Dubowitz said while controversy over the field, especially overdiagnoses of abusive head trauma, mainly plays out in the courts and in the media, people within the scientific field mostly agree the processes followed work well.

"The field has a problem with some folks who have prominently made themselves available to testify, usually in criminal trials, or high-powered civil trials, who are considerably outside the mainstream... and that has been dangerous in sowing doubt and disdain," Dubowitz said.

Dubowitz said child abuse pediatricians often consult with each other and experts in other fields when making their evaluations.

He said while he does not make the final decision about whether a child should be removed, in some cases, his medical examination does hold more weight in judges’ decisions about custody than other testimonies.

"In the example of I have a 2-month-old baby with four unexplained rib fractures, and the baby's otherwise healthy, and there is no other explanation,” Dubowitz said. “Let's say in that situation, I conclude this baby was probably abused.

“In that kind of case, that information is going to hold sway. What the social worker thinks of how the mom is interacting with the child, et cetera, is going to be less consequential."

"There's nothing that emerges on psychological testing or psychiatric interviews that lets you rule in, or disconfirm, medical child abuse.”Marc Feldman, a medical doctor and Clinical Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Alabama

In many of the cases that are publicly criticized, parents get independent psychological evaluations. They say that those evaluations prove the child abuse pediatrician’s report is incorrect.

But Marc Feldman, a medical doctor and Clinical Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Alabama who has studied medical child abuse for 30 years, disagrees.

Feldman said he does not think one can rule out medical child abuse through psychological tests because even trained professionals often cannot detect deception.

“I think it is advisable to do psychological testing, if possible, but there's nothing that emerges on psychological testing or psychiatric interviews that lets you rule in, or disconfirm, medical child abuse,” Feldman said.

How common are false accusations?

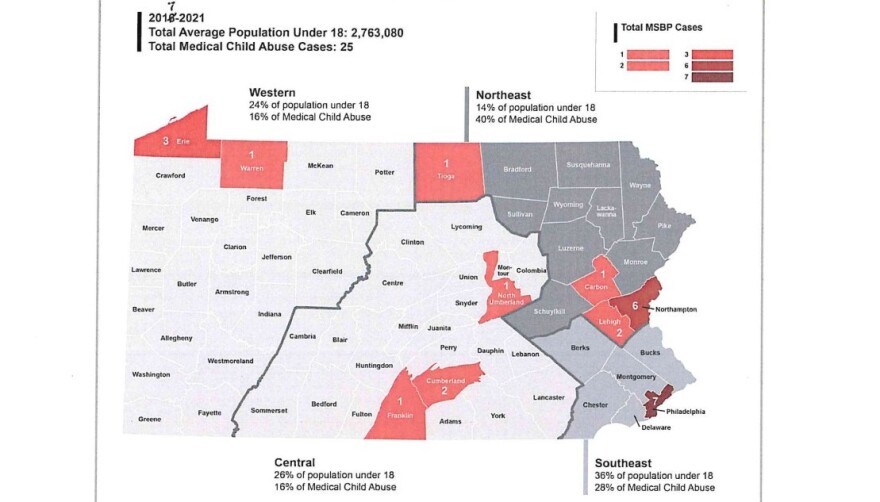

In his report, Pinsley cited that the Northeast region of Pennsylvania had 40% of the state’s medical child abuse cases from 2017 to 2021, despite having 14% of its population younger than 18.

Pinsley said that's an indication there may be more false accusations in the county.

Lehigh Valley Parents’ Medical Rights Group leader Kim Steltz said she has now heard about 70 cases of parents saying they were falsely accused of child abuse by LVHN doctors, but said there could be many more cases of parents who are afraid to come forward.

Feldman has written about false diagnoses of the disease but said he thinks such cases are rare. A study he conducted in 1999 found 2 to 3.5% of cases were misdiagnosed.

No widespread studies have been done on the issue since then, and he said he thinks there needs to be systemic studies into the frequency of misdiagnoses.

But Feldman said he also thinks cases of medical child abuse often go undetected in many areas because of a lack of education among health care professionals and law enforcement officials about the condition.

“It's often only when a child dies and we see the same pattern occur with a new child in the family that many people pick up that this is obviously serial medical child abuse,” Feldman said.

Feldman said that while Pinsley’s report cites a higher number of medical child abuse cases in Lehigh and Northampton counties as a sign that overdiagnoses are happening, it could be that the local CAC is better at detecting cases than other areas of the state.

That is the case in Tarrant County, Texas, Feldman said. There, the sheriff’s office has filed 10 criminal charges for medical child abuse in the past four years, which is higher than many places.

A detective in the county, Mike Weber, said the high number of cases is not because of overdiagnosis. Rather, he said, the county has a system for detecting and pursuing such cases while many counties struggle with a lack of education and processes for investigating the abuse.

“The system is not set up to handle this abuse in any way, shape or form," Weber said. "That is for sure. And child abuse pediatricians are so left out in the ledge.”

'Who gets to be an autonomous parent'

Weber travels nationally to train police departments on how to investigate cases of medical child abuse. He also wrote a set of guidelines for the investigations for the FBI’s Law Enforcement Bulletin.

Weber and Feldman are both on the American Professional Society on the Abuse of Children's medical child abuse subcommittee.

Weber said police detectives can contribute to investigations by looking through social media records, investigating private messages and interviewing people in the child’s life.

But he said many police departments and social workers are not educated on medical child abuse, meaning an investigation is often not properly followed through.

“In many ways, it differs who gets the chance for the opportunity to make their own decisions for parenting, who is given grace when they err and who gets to be an autonomous parent and who does not.”Professor in Public Health and Policy at the University of Rochester Mical Raz

Professor in Public Health and Policy at the University of Rochester Mical Raz wrote a Slate article about "Take Care of Maya" to give more context to what she sees as a flawed child welfare system.

Raz has studied the child welfare system in Philadelphia. She and others have found that people of color and people of lower socioeconomic backgrounds are more likely to be falsely accused of abuse.

"I realized that a lot of choices I made… could be framed as neglectful choices and could result in investigation and removal if my address, ZIP code or skin color was different,” Raz said.

“In many ways, it differs who gets the chance for the opportunity to make their own decisions for parenting, who is given grace when they err and who gets to be an autonomous parent and who does not.”

Raz said she is not sure if that is the case for medical child abuse because the National Center for Child Abuse and Neglect does not collect statistics specifically about medical child abuse.

What happens next?

Pinsley’s report recommends the county launch an independent investigation into Children and Youth Services, require a second medical opinion in custody cases and that LVHN have an outside agency review its handling of child abuse cases.

Lehigh County Commissioners Chairman Geoff Brace said at the board's latest meeting that it is conducting a legal review of whether it has the right to investigate the department and require a second opinion.

Pinsley sent them a memorandum from Attorney Elliot Love saying the county does have the legal right to do both things.

But whether a second opinion should be legally required is contested.

"I would hesitate to even comment on a general idea like this without seeing a well-crafted, fully-developed proposal of how this would work."Howard Dubowitz, director of the Center for Families at the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore

Weber said a second opinion is required in Texas, but usually is done by another child abuse pediatrician, and Pinsley wants the second opinion to be from a specialist in the disorder that the child presents as having.

Weber said he supports a second opinion as long as the doctor takes the time to review all the medical records and does not rely on the history of the parents.

But he said it would likely be difficult to find a physician willing to do that since there can be thousands of pages of records in these cases.

Dubowitz said second opinions are important when cases are ambiguous, but raised logistical issues with who would agree on the physician and who would pay for the consultation if it were required legally.

"I would hesitate to even comment on a general idea like this without seeing a well-crafted, fully-developed proposal of how this would work," Dubowitz said.

Steltz said the Parents’ Medical Rights Group will continue to hold demonstrations until Pinsley’s recommendations are met and Esenerio-Jenssen is fired.

The group showed up at the last meeting, sharing its stories with the board again and asking for action.

“This is not a game,” Steltz said. “Families and children are not a campaign, and they're not politics. This is my family, and it's their family and it's your family.

"But most importantly, it is the families that this has not happened to yet.”