(Fifth of five parts — See the entire series)

BETHLEHEM, Pa. — Just a few years ago, warehouses seemed to spring out of Lehigh Valley farmland like mushrooms after a storm, if a mushroom thrived on easy access to major highways.

It’s a different story today.

“From the end of 2020, through the middle of 2022, at any given time, there was about 10 million square feet [of industrial real estate] under construction” in the region, said Joseph Gibson, associate director of research tracking Pennsylvania for CBRE, a commercial real estate services firm. “That is a tremendously high, noticeable level.”

In 2021 alone, 8.4 million square feet of space came online in the region, said George Lewis, special assistant to the president of Lehigh Valley Economic Development Corp.

By comparison, less than 4 million square feet of warehousing was completed in 2023.

“It's like half the new space coming into the market in just a two-year period, and the amount of industrial space under construction has fallen off as well,” Lewis said.

Gibson said at the end of last year there was less than 2 million square feet of industrial space under construction — about one-fifth of the pandemic-era peak.

“I'm not saying there's never going to be another warehouse built in Northampton County or the Lehigh Valley, of course. What I am saying is this gold rush … is coming to an end.”Lamont McClure, Northampton County executive

CBRE’s most recent quarterly report shows that, as of the end of June, there was about 1 million square feet of industrial buildings under construction in Lehigh and Northampton counties.

“We were averaging, call it, about 6 million square feet under construction at any given time before the pandemic. So, right now, it is a lull even compared to that,” Gibson said.

While the Valley’s warehouse market is by no means in free fall, experts say it has undeniably slowed. Less clear is whether the slowdown represents a temporary lull, or whether the controversial warehouse boom has come to an end.

A changing market

According to CBRE’s most recent quarterly report analyzing the region’s industrial real estate market, the annual rate at which occupants are filling industrial buildings has declined each year since 2021.

As a result, more warehouse and industrial space is sitting empty. Vacancy rates have been climbing for a year and a half in the Valley, reaching 6.7% at the end of June.

Landlords’ asking rents for Class A space stayed roughly flat since the fourth quarter of 2023, suggesting the rental market is approaching a new equilibrium.

“Developers continued to react to current conditions,” the CBRE report says. “While demand may continue to soften, the market is not positioned to add excess supply via construction in the near-term.”

Some cooling as the pandemic waned is not surprising.

“Demand hit a fever pitch that had never been reached before, and quite frankly, we all knew was unsustainable,” Gibson said of that time.

Online shopping exploded in 2020 as many customers avoided human contact. In turn, the network of warehouses that makes e-commerce possible had to grow just as quickly.

The portion of retail sales that take place online stayed about flat for much of 2021 and 2022. Growth resumed in 2023, albeit more modestly, according to research from CBRE.

As the pandemic surge wore off, many of the companies that need large-scale warehouse space pulled back on expansion plans — and demand for new warehouse space fell.

In another sign of the changing market, a surge of third-party logistics companies have offered up some of their warehouse space for sublease over the past year, doubling the total amount of space available for sublease.

Some indicators point to strong underlying demand for the buildings; lease activity, for example, has started to climb for the region after reaching a low in mid-2023.

“This isn't necessarily an indication of a slowing market. It's just a little bit more of a less frothy market and a little bit more of a stable market,” Gibson said.

In large part, the recent decline comes from higher borrowing costs that have risen with the Federal Reserve’s series of rate hikes from March 2022 to July 2023.

“It's high interest rates,” Gibson said. “Even a finer point, it's uncertain interest rates. If [rates were] higher, but we knew they were just going to be there for a long time, people can then just bake that into their financial models.”

The Federal Reserve’s rate-setters have kept borrowing costs flat for the past few months, but have telegraphed that a cut is likely coming in September.

“We’ll know when we see interest rates come down and the market open up a little bit more for developers in general,” Lewis said. “whether what we're seeing now in terms of less development here is interest-rate driven, or if it's something more permanent.”

Groundswell of opposition

Outside the market, the Lehigh Valley’s appetite for warehouses has undergone a shift. Resident groups have sprung up in opposition as more and more construction has happened.

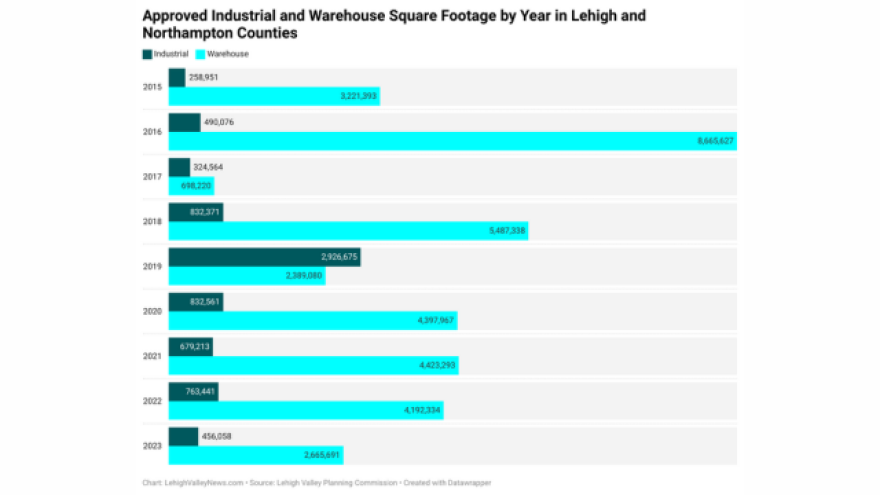

From 2015 through 2023, about 44 million square feet of industrial and warehouse space was approved in Lehigh and Northampton counties, according to the Lehigh Valley Planning Commission, equivalent to more than 1,000 acres.

In his State of the County address last year, Northampton County Executive Lamont McClure said the county didn’t need any more warehouses.

“I'm not here today to declare that the era of warehouse proliferation is over. But what I am here to tell you today is that the era of warehouse proliferation is coming to an end in the Lehigh Valley, and in Northampton County in particular,” McClure said in an interview earlier this year.

He traces his own personal opposition to “warehouse proliferation” to late 2017. A former county councilman, McClure had already become accustomed to “white-knuckling down 78, in fear for my life, because there's a truck to the right of me in a truck to the left of me,” he said.

But his opinion crystalized, McClure said, when he learned that the county is a “net importer” of workers, with more people commuting into the county for work than traveling from homes in the county to jobs elsewhere.

New logistics buildings represent a balancing act between economic growth and the burdens of hosting them, he said, and the inflow of workers means that balance has shifted.

“I concluded that since we're importing workers, since there's enough jobs in these warehouses already for all of us who live here, we don't need any more,” McClure said. “Because it's adversely affecting the quality of our life, and it's potentially adversely affecting the quality of our health, and it's making our roads more dangerous.”

Though his personal opposition is several years old, he said, the actual slowdown has only emerged in the last year. McClure attributes it in part to outside economic forces, and in part to growing municipal resistance.

“I'm not saying there's never going to be another warehouse built in Northampton County or the Lehigh Valley, of course,” he said. “What I am saying is this gold rush … is coming to an end.”

Some of the region’s local governments have felt the economic impact of slowing construction. In an era of rising prices, quickly accelerating development once kept government budgets in balance with tax revenues.

The recent slowdown has created financial pressure on local governments as new development can no longer outpace rising costs.

At a Parkland School District budget workshop in April, for example, district Business Administration Director Leslie Frisbie said officials would need to raise property taxes because of slowing industrial development.

Though her district had seen an uptick in residential projects, it was not enough. A new single-family home would generate about $5,000 in property tax revenue for the district, Frisbie said, compared to $500,000 from a warehouse.

“We're starting to see that slow,” she said. “Now we need to come up with another funding source, and the reliance on real estate tax increases is really where.”

Come June, the school district approved a budget which raised property taxes by about 5%.

The future

The most likely scenario in the coming months and years, the experts said, is that construction rebounds once interest rates drop, buoyed by consistent demand from e-commerce, logistics and distribution companies.

“There's no reason not to think that once things become a little bit more economically certain that we don't see a return to something a little closer to pre-pandemic levels,” CBRE’s Gibson said.

The modest growth of e-commerce over 2023 points to a more durable trend, according to a report from CBRE. The company’s researchers project the portion of retail transactions conducted online will continue to grow over the next decade, which in turn would drive demand for more warehouses.

Further demand could come from overseas companies looking to open operations in the U.S. to insulate supply chains from recent disruptions to global shipping.

As long as companies want more warehouses, experts said, the recently-completed buildings will eventually find tenants — and construction will need to accelerate again to keep up.

Many developers have not been idle over the past year, CBRE Executive Vice President Vincent Ranalli said. They will have projects ready to begin construction once the market is more favorable.

As a result, Gibson said, the market is probably as soft as it is going to get. But a complete recovery — even to pre-pandemic levels — is not guaranteed.

“I'm not of the camp that is predicting an end of this boom. I just don't see it coming,” Ranalli said . “What could slow it down is lack of available sites.”

Said LVEDC’s Lewis: “If we don't see the development pick up to, say, 2020-2021 levels with lower interest rates available to builders, then I think, yes, we probably have gone over a tipping point in terms of how much development we're going to be able to accommodate here.”

Places to build

Then there is the issue of available space.

It doesn’t matter how high demand for new warehouse space climbs, or how cheaply developers can borrow money, if there is nowhere left to build in the Lehigh Valley.

“It is becoming harder and harder to develop in the Lehigh Valley,” Ranall said. “There’s less sites that are out there that are close to the highways that have utilities that, you know, are ready to go. And certainly there's more opposition.”

It is not enough for a potential warehouse site to be large enough, close to major highways and up for sale. The land must also be zoned for a warehouse, or the municipality responsible for the site must be willing to grant exceptions.

Popular resistance to large-scale warehouse construction has narrowed the universe of possible land for large-scale industrial development.

In some places — for instance, in Upper Mt. Bethel Township in the Slate Belt of Northampton County — voters have installed warehouse-skeptical officials in local offices who have taken a less-than-accommodating approach to developers proposing large industrial projects.

At the same time, both Lehigh and Northampton counties have prioritized spending to preserve farmland, specifically to stave off future development.

“More and more municipalities like Moore Township and Lower Nazareth and Upper Mount Bethel and Hanover — they're all fighting back. It's going to become less and less interesting to these folks,” McClure said.

Opposition from municipalities responsible for signing off on new buildings could mean a more difficult and expensive application process. Most projects depend on getting permission from local government to go forward.

“If developers have access to capital again,” Lewis said. “will there be municipalities that are open to considering, you know, proposals or applications from developers for 300,000-square-foot buildings, 500,000-square-foot buildings, million-square-foot buildings?”

“You can see it if you drive either west on [Interstate] 78, or north on [Interstate] 81, where more projects are moving sort of further out from the immediate Lehigh Valley into Berks County, Schuylkill County.”George Lewis, Lehigh Valley Economic Development Corp.

Lewis, Gibson and Ranalli all predicted the warehouse boom will not end in the near future thanks to persistent demand, but that the Valley will probably run out of space eventually.

Even on the other side of this tipping point, the Lehigh Valley’s many warehouses will not go anywhere, and warehouse construction will not stop altogether.

“When will they stop building office buildings in Philadelphia, right? Well, they have,” Gibson said, with a new addition “every once in a while,” typically as part of a redevelopment project.

Similarly, the Lehigh Valley’s warehouse market may reach a point of stasis.

“Maybe they're tearing down old buildings that aren't functional anymore and they're building new class-A buildings,” Ranalli said. “A lot of the low-hanging fruit is gone, so you've got to get creative.”

But the Lehigh Valley is not the only place where conditions have been ripe for warehouse construction, with land, an available labor force and access to the highway network. Unless something happens to curb demand from businesses that need warehousing, it will not cease to be built when the Valley runs out of suitable space.

Instead, the wave of warehouses will continue to move geographically, as it has already. Gradually, large-scale industrial development has shifted away from the Valley proper.

“You can see it if you drive either west on [Interstate] 78, or north on [Interstate] 81, where more projects are moving sort of further out from the immediate Lehigh Valley into Berks County, Schuylkill County,” Lewis said. “Or further up Route 33, like towards Wind Gap.

“What's clear is not changing is that the companies want to be in this area, because we have that sort of convenient access to the Northeast markets that they want to get to,” he said.