UPPER MACUNGIE TWP., Pa. — Scott Keller moved to the township 26 years ago, and since then, he says a problem has been growing.

“Probably six, eight, ten times a night, you hear these Jake brakes out on the road and they echo through our little valley here,” Keller said.

“Jake brakes,” or engine brakes, are a type of brake system on tractor trailers that use the engine to help stop the vehicle — and make more noise, especially when the vehicle is not up to code.

Keller said he has spoken to about 100 residents who have complaints about the noise from trucks on Shantz Road, which is about a half-mile away from his house.

He presented signatures and letters from them at a March township meeting about potential changes to the local noise laws.

“We're building barriers, we're planting trees. One of my neighbors invested $20,000 to try and block noise,” Keller said at that meeting.

“All of our windows are closed because of the traffic. We can't deal with the noise. Especially in the nice weather, it’s very painful. If we're outside, we’re on the side of the house away from the noise.”

Noise is just one complaint residents have about the large industrial corridor that runs through the center of Upper Macungie.

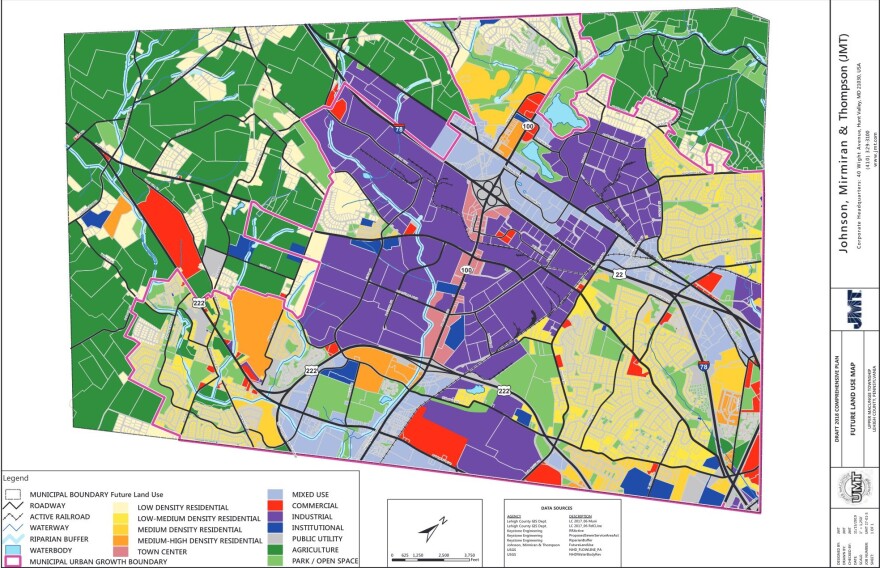

About a quarter of the township’s land is zoned for industrial use, according to its comprehensive plan.

And a lot of that space is used for warehouses. In 2017, about 12% of the township’s total acreage was taken up by wholesale distribution and warehouses, up from 2.5% in 1996.

That amount has only grown, with more industrial buildings having since been built and approved, such as three warehouses together covering 2.6 million square feet at the former Air Products headquarters.

These buildings have become the center of a debate about how much the township can and should limit further warehouse development — and how to cope with the ones that are already there.

How did the township get here?

When Sunny Ghai was growing up in Upper Macungie in the 1970s, the landscape looked very different.

“Most of what we see now as any kind of development, it used to be just cornfields,” Ghai said.

“I mean, I went to Fogelsville Elementary School, and on both sides of that on Route 100 — it’s nothing like what we had before.”

Ghai, who is now the vice chairman of the township Board of Supervisors, got started in politics as a resident concerned about a proposed warehouse development behind his home.

He said one of the main reasons for the explosion in development is the township’s location.

Former supervisor Kathy Rader worked for the township in several positions starting in 1985. When she retired, she said in an interview the land use laws for the township were made around when she first started — before there was even widespread use of the Internet.

“They were looking for more manufacturing. They never dreamed of this,” Rader said.

“When you manufacture something, you also have to have warehousing with it because once you make something you need a place to put it. And warehousing is what took off.”

Several highways run within the township borders, such as Interstate 78, Routes 22 and 100, as well as the Northeast Extension of the Pennsylvania Turnpike.

That means truck drivers can get to about 30% percent of the U.S. population within 10 hours – the maximum time they are allowed to drive in a day.

Those highways intersect in the center of the township, creating what township Director of Community Development Kalman Sostarecz calls a “donut,” with industrial development in the center, and houses, commercial development and farmland on the edges.

About a thousand acres of that farmland is preserved, Sostarecz said.

What is a warehouse, anyway?

Traveling east down Shantz Road, drivers will find themselves in the middle of one of the township’s industrial zones, with dozens of rectangular, gray and massive buildings.

One of those buildings houses a returns distribution center for Inmar Intelligence. Retail operations send returned products to the Breinigsville facility for workers to sort and determine whether they are still in good condition.

But many other operations happen in these similar-looking buildings.

“Each of these buildings have a lot of similarities in the way they look,” senior manager at Inmar Christopher Cuozzo said. “But the guts are a lot different.”

Manufacturing warehouses store completed goods for distribution, for example, and retailer warehouses distribute products to stores. E-commerce warehouses fulfill Internet orders, and storage warehouses keep products long-term.

“The keyword for all of them is order fulfillment,” said Todd Sullivan, senior project manager at GXO Logistics in Bethlehem. “We are storing goods you need until someone wants it.”

Different types of warehouse uses can have different impacts on the surrounding area.

For example, Inmar Intelligence’s Breinigsville warehouse generates at most 20 trucks a day, according to Cuozzo. A different Upper Macungie warehouse, Americold, is set to generate 490 truck trips once a planned expansion is complete.

"Making things and getting those things to the market are, as we look at it, all part of one integrated industrial market.”George Lewis of the Lehigh Valley Economic Development Corp.

George Lewis of the Lehigh Valley Economic Development Corp. said some people want to promote manufacturing instead of warehousing, but it is “really difficult” to separate the two.

“In many cases, a lot of that activity goes on in the same building,” said Lewis, special assistant to the president and chief executive officer.

“We're a manufacturing hub in Lehigh Valley. It's a big part of our regional economy. And making things and getting those things to the market are, as we look at it, all part of one integrated industrial market.”

Working in a warehouse

Back at Inmar Intelligence’s warehouse, the floor workers review about 950,000 returns per week.

They check if products have been opened, inspect the edges of rugs to see if they’ve been frayed and make sure no one left anything inside their returned jeans.

“Oddly enough, we'll find undergarments,” Cuozzo said.

Workers then inventory the products and load them into trucks to be sent back to the original company or to other buyers.

The floor workers described the job as repetitive and hard on their bodies. But they said that their tasks were easy to learn and that the job pays well — about $15 to $20 an hour, Cuozzo said.

Employee Martha Cabrera came to Inmar as a scanner and worked her way up to become a production supervisor. She said the work is challenging, but there is always something new to learn.

Cabrera said she has heard people on the news talk about how they don’t want warehouses in the area.

“They do bring a lot of revenue to the area,” Cabrera said. “But they don’t look at it from that perspective; they look at it as we’re going to be damaging. But not every warehouse damages the area.”

Benefits of warehousing

About 175 people work at Inmar. Lewis said the LVEDC estimates manufacturing and warehousing sectors of the economy combined provide about 80,000 jobs in the region.

The competition for workers has driven the wage rates up for the entire market, he said.

“Wage rates in the Lehigh Valley are $20 to $22 an hour for even the entry level, lowest-skilled job,” Lewis said.

“So you can have people working in those big boxy facilities who are moving boxes around or driving forklifts or driving trucks who are making three times the state's minimum wage.”

John Pollock, Principal at developer Trammell Crow Co., answered questions about warehouse development via email.

Pollock wrote that the industry brings an “entire ecosystem of jobs” besides people who work on the warehouse floor, including opportunities for accountants, landscapers, attorneys, engineers, caterers and more.

The industry can also entice other industries to come to the Valley, according to Pollock.

“As warehousing steadily grows in the Lehigh Valley, it raises the national/international awareness of the region as business friendly, enticing companies to create or expand headquarter operations here due to the region’s strong logistics network and workforce,” Pollock wrote.

The economic benefits don’t end at employment.

According to Lehigh County data gathered in May 2024, the total assessed value of all the land in Upper Macungie is about $4.7 billion.

That’s behind only Allentown, which has about three times as many parcels of land.

The tax revenue from industrial facilities has allowed Upper Macungie to keep its tax rate low, according to Sostarecz.

The township’s property millage rate is 0.64 mil, and the average residential property owner pays approximately $235 per year in township taxes, Sostarecz said.

“That gives you full-time police, gets you all the parks and recreation, gets the full-time public works department, gets you fire services — all those are volunteer, but the township does pay a lot of money towards its fire services,” Sostarecz said.

“So if you think about it, $235 gets you everything you need to live comfortably.”

“What that does is… we need to come up with another funding source, and real estate tax increases are really where we can make that up.”Parkland School District Business Administrator Leslie Frisbie

Sostarecz said the other benefit of warehousing is that “their demand on our services is relatively low.”

“Police response is very low, fire response is very low,” Sostarecz said. “So they're paying a significant tax based upon their assessed value, which definitely does assist in, essentially, keeping in check the typical residential tax bill.”

In recent budget talks at the Parkland School District, Business Administrator Leslie Frisbie cited slowing growth of the commercial and industrial sectors in the district’s municipalities as a main reason for 2024-25’s 5% tax increase.

“What that does is… we need to come up with another funding source, and real estate tax increases are really where we can make that up,” Frisbie said.

Downsides of warehousing

For years, residents have complained about the negative impacts warehouses have brought to the township.

In 2019, with resident input, Upper Macungie adopted a new comprehensive plan, or a guideline for future developments.

The plan calls into question the township’s ability to continue to sustain industrial development.

“While UMT is in the path of development, it is substantially developed and is at the break point of its ability to mitigate impacts of the existing warehouse cluster and any future expansion of this cluster,” the plan reads.

The plan listed several negative community impacts from warehouses, including:

- Poor air quality from exhaust pollution;

- Noise, light, and glare from operations;

- Truck traffic congesting roads and “impacting the safety of the traveling public”;

- Cost of traffic safety enforcement;

- Deterioration of existing roads and the need for costly road improvements;

- Impacts on water quality due to large areas of impervious surface, or paved places where rainwater can’t go into the ground;

- Limited ability to provide safe pedestrian and bicycle connections.

Ghai said it’s difficult to know whether the tax revenues from warehouses offset the costs from the improvements they require.

“It’s hard to know how to even measure that,” Ghai said.

Recent results of air monitoring project Lehigh Valley Breathes show that fine particle pollution in the Lehigh Valley is highest near warehouses and highways.

The township's noise ordinance — the law that determines how noisy business operations can be — allows for a maximum noise level of 75 decibels at any time.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website, "noise above 70 dB over a prolonged period of time may start to damage your hearing."

Many residents in the region have noticed their roads being damaged by tractor trailers — even Sullivan, a warehouse manager.

“Right at the bottom of Commerce Center Boulevard [in Bethlehem], where the stop sign is as you leave the park, you can tell the road is warped,” Sullivan said.

“I mean, these are heavy, heavy vehicles transporting a ton of materials.”

Lewis said these issues are typical of any municipality with industrial growth.

“The challenge is to have the right amount of industrial development, have the right amount of job opportunities and growth, without overtaxing the assets of the region,” Lewis said.

“Because you can, if you're over-developed, get past the tipping point as well, where that also impacts the people who are willing to live there — the quality of life that they're going to find there.”

Pollock of Trammell Crow said that while the people who are most vocal about warehouse uses are opposed to it, many have benefited from the industry.

“Not all residents share the views of the most vocal opponents — many Lehigh Valley residents have made a career out of the opportunities brought to the region by the logistics industry,” Pollock said.

Managing the impacts

There are often large areas of grass between Upper Macungie’s industrial buildings and the roads, as well as trees.

That’s by design. Township laws require industrial developers to add buffers, plant trees and create small hills called berms to obscure buildings, control stormwater runoff and install sidewalks, if possible.

Some developers offer more than what is required in an attempt to be good neighbors.

For example, Air Products will pay to create hills around their warehouses that will be large enough so that nearby neighbors likely won’t be able to see them.

Pollock wrote that these contributions are most likely to happen when government officials “treat the relationship between developers and municipalities as a partnership.”

“If there is a partnership between developers and municipalities/local officials from the outset of a project, opportunities will often arise for developers to make voluntary contributions to things around the municipality, such as parks, playgrounds, trails, etc.,” he said.

Air Products also will pay to straighten out the sharp curves on Cetronia Road and add a cul-de-sac called Cetronia Circle for nearby houses to access the road.

Upper Macungie is working to change its noise ordinance and may lower the maximum noise level businesses can create.

"As long as you're ordering stuff off of Amazon — and I do — you can't complain about the trucks. You have to learn how to coexist.”Upper Macungie resident Scott Keller

If the law passes, the township may require new businesses to install noise barriers or find other ways to lower the sound of operations. Existing businesses would be “grandfathered,” meaning they would not need to follow the new regulations.

Keller, the resident who collected signatures from residents about the truck noise, says he doesn’t like living with warehouses nearby at all, but he’s choosing to focus on what he can change.

“We have to learn how to coexist because e-commerce is not going to stop,” Keller said. “As long as you're ordering stuff off of Amazon — and I do — you can't complain about the trucks. You have to learn how to coexist.”

Keller attended a workshop about the new noise ordinance a few months ago to voice his complaints. He’s also working with the township police department to get more officers to stop and fine trucks that aren’t up to code, which generate more noise.

What’s next?

Sostarecz, Upper Macungie's community development director, said most of the large industrial parcels in the township have been developed, meaning there likely won’t be many more warehouses built in the township.

The only large parcel of land that is zoned industrial, is undeveloped and does not have an approved development plan is a parcel just west of Church Street Park in Fogelsville, between I-78 and Old U.S. Route 22.

The land is currently used for agriculture. It is owned by Jaindl Land Companies.

Upper Macungie is working on changing its zoning ordinance and its subdivision and land development ordinance, or SALDO.

Those laws determine which types of developments are allowed in certain areas of the township, and what they can be like.

Sostarecz emphasized that the revision is meant to affect the long-term growth of the township and likely won't have a short-term effect.

The revisions won't be able to get rid of any buildings, for example.

"What's here is here," Sostarecz said.

The zoning and SALDO reviews come after the township adopted a new comprehensive plan in 2019, which outlined a vision for future developments in the township.

Sostarecz said zoning and SALDO revisions typically follow comprehensive plans. But since the township has changed since the plan was adopted, some revisions might be based on what residents say, even if the plan contradicts their comments.

Ghai said the township has restarted the revisions process after former Township Planning and Zoning Administrative Specialist John Toner III left his position and the new township planner, Meredith Keller, began leading the process.

Keller said she comes from a historic preservation background, where one of the main tenets is, “You can only manage change, you can't prevent change.”

“Planning is absolutely the approach to managing change. You can anticipate it, but you can't stop it,” Keller said.

“And so if there is a concern that we're losing farmland to industrial development, or subdivision for housing, the way to manage it is to create aspects of your zoning ordinance that address it. And I think we do a good job of that.”

COMING TOMORROW: THE CONFLICT WITHIN

The explosion of warehouse development in the Lehigh Valley has led to inevitable conflict – developers versus neighborhoods, elected leaders versus constituents, and neighbors versus neighbors. One community is living it right now, on all fronts.