ALLENTOWN, Pa. — A yellow school bus pulled up to its designated pick-up spot, where a small group of elementary school students stood waiting near the curb in a busy residential area.

But as the bus activated its warning lights and began to slow earlier this week, the usual ripple effect on traffic took hold and the bus driver’s focus immediately shifted to her surroundings.

Would other drivers try to rush past before the bus came to a complete stop? Would they obey the law and halt once the red lights began flashing and the stop arm was activated? Were the students outside alert? Could the other drivers see a child preparing to cross the street?

“These questions go through your mind every day. We have a lot of people who will race to pass the bus before we stop,” a driver for Student Transportation of America told LehighValleyNews.com.

The driver, who didn’t want her name published because she’s not authorized to speak for the company, described a “tense” coexistence between school buses and motorists in Allentown, where officials have issued at least 3,151 citations for school bus stop arm violations this year, the city’s police chief and BusPatrol, the stop-arm enforcement technology provider, confirmed.

With 58 school days on record as of April 4 — not including two days of flexible instruction in February — that equates to an average of 56.2 violations per weekday.

The rate exceeds that of larger cities like Pittsburgh, where over 9,000 citations reportedly were issued over nine months — averaging 38.6 violations per weekday.

In response, the Allentown Police Department has turned to social media to share educational resources about Pennsylvania’s School Bus Stopping Law, Chief Charles Roca said.

Neighboring municipalities also have seen a significant number of violations, though not to the degree of Allentown:

- In Bethlehem, Lt. William Audelo reported at least 437 approved violations so far this year.

- In Salisbury Township, Officer Bryan Losagio, the department’s traffic coordinator, said at least 266 violations have been approved this school year, and 342 were issued over the past calendar year.

Since the township began using automated stop-arm technology in December 2021, 643 citations have been issued in Salisbury, Losagio said.

Expansion of school bus safety measures

The journey to improving traffic safety for students in the Lehigh Valley began in 2017, when Allentown mother Amber Clark pulled her young daughter from the path of a speeding car while trying to board her bus — just three days into kindergarten.

“My daughter still takes the bus,” Clark said Thursday. “She’s turning 13 this year. She was only 5 when this all began.”

Despite the years that have passed, Clark’s dedication to advocating for school bus safety hasn’t wavered.

Reflecting on that day, Clark recalled how the incident sparked an immediate sense of urgency. She began recording videos on her phone of cars passing stopped school buses.

Through social media and word-of-mouth, she connected with other concerned parents and began lobbying local officials, including city council members and school district leaders.

Her advocacy soon extended to the state level, where she continued pushing for protections for children, lobbying then-state senator Pat Browne, R-Lehigh, on the issue until he vowed to write a bus-camera bill.

State Rep. Mike Schlossberg, D-Lehigh, also jumped on board and agreed to work on a House version.

The legislative process played out at warp speed. Within 17 months a law was enacted, and today many school districts are using automated cameras to crack down on drivers who blow past stopped buses.

“I had numbers from (bus camera) studies that I came across and data from a pilot program in Allentown in 2020. So multiplying that out I came out with horrid numbers of potential violations, even back then,” Clark said.

“So to hear there are more than 3,000 violations this year so far it doesn’t surprise me, and it also horrifies me,” she said.

In response, the Allentown School District said it's working with BusPatrol and the city to analyze the data it receives and increase patrols in areas where the highest number of citations have been issued, including Hanover Avenue on the east side and along the Seventh Street corridor, which runs through the heart of Center City.

“The safety of our students is one of our top priorities, and that includes how they get to and from school,” ASD communications manager Melissa Reese said.

“Changing driver behavior will take the collaborative efforts of our entire community, but we are hopeful that citations can help raise awareness about traffic safety, and keep our students safe,” she said.

35,000 buses across 20 states

In Pennsylvania, drivers who illegally pass a school bus with flashing red lights and an extended stop arm face civil citations — carrying a $300 fine. These violations must be mailed to the registered owner of the vehicle within 30 days.

But the enforcement technology is expanding well beyond state lines.

Steve Randazzo, chief growth officer at BusPatrol, oversees sales, government relations, marketing and community partnerships. He shared the scope of the company’s operations.

“We operate on about 35,000 buses across 20 states, including around 6,000 in Pennsylvania,” Randazzo said.

That includes 139 buses with cameras in Allentown, the district confirmed.

Randazzo explained that many of Pennsylvania’s enforcement programs are relatively new — often just a year or two old. That presents challenges in changing driver behavior.

“Behavioral change and the psychology of the reckless driver is very complex and very difficult to change,” he said. “I never go into a presentation with a school district or a police chief or a mayor or school board member and say, ‘If you do BusPatrol, no one will ever break the law again.’

“School buses – it's a moving target. The school bus stops change every year, right? People move into the community, kids move out of the community.”

That’s why, Randazzo emphasized, BusPatrol takes a comprehensive approach.

“The way we think about the problem is one, we approach it from a full fleet perspective,” he said. “We feel like the secret sauce, part of the secret sauce to the behavioral change, is this idea that you equip every bus in a community.”

According to Randazzo, when enforcement and education is applied consistently across a community, people begin to recognize the risk.

“People start to get that psychological sort of trigger in their mind that, ‘Oh, man, anywhere in Allentown, if I pass a school bus, I'm going to be held accountable for that.' It's not just here or there, or this part of town or on the street.”

He added that many violators claim they simply didn’t see the bus.

“We always chuckle at that because a school bus is hard to miss,” Randazzo said. “It's large. It's yellow. It's got red flashing lights, yellow flashing lights. It has an arm that sticks out into the road.

“If you didn’t see the bus, it really begs the question, 'Were you paying attention enough?'”

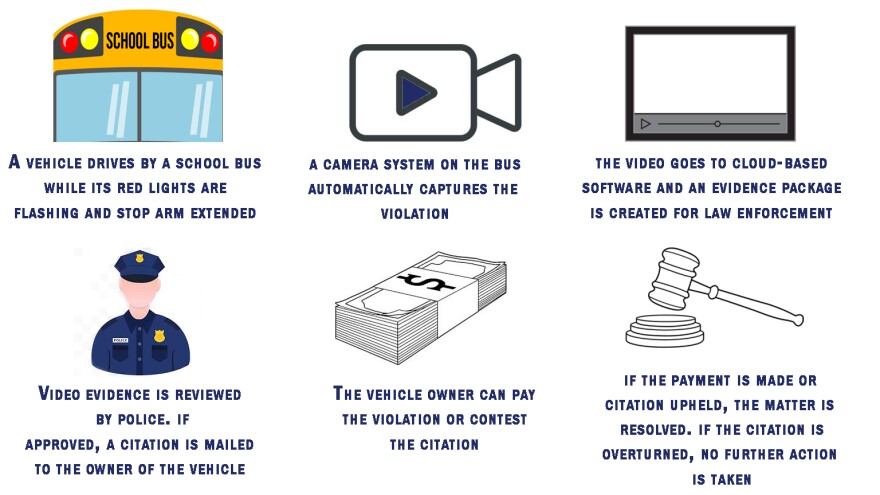

What happens after a violation is recorded, Randazzo said, depends on how each community uses the data.

“I call it the three E's – enforcement, education and engineering – and that's really what you're hearing in the Vision Zero community. If you're familiar with the concept of Vision Zero, it’s the idea that no one should lose their life senselessly to traffic violence.”

Vision Zero and Safe Streets For All

Allentown officials have adopted the Vision Zero strategy, vowing to eliminate pedestrian fatalities by 2030. The city is aligning the strategy with its recently launched Safe Streets for All initiative, aimed at redesigning streets and implementing safety improvements.

A city-appointed steering committee for the project had already identified Hanover Avenue as a particularly hazardous corridor — earning the nickname “Hanover Racetrack” from residents due to frequent speeding.

To aid in enforcement, BusPatrol provides partner communities with monthly heat maps showing top ticketed locations.

“Then it’s up to the community to act on that data,” Randazzo said. “I've seen communities send live law enforcement, targeted enforcement to those areas.”

He gave an example: “If we show you that an Allentown bus stop between 3 and 4 p.m. is the top ticketed location in the city, you send an officer there. You're going to continue to drive down that dangerous behavior.”

The data also can help to inform broader safety decisions, he said, like adjusting routes or relocating bus stops. Allentown's heat map shows Hanover Avenue and Seventh Street as hotspots for offenses, according to the school district.

Said Randazzo: “Now we have actual data that show us where the most dangerous locations are in the community, and that leads to a more thoughtful, more purposeful, more safety-driven, school bus routing tool that you can use.”

These actions – coupled with community education and engagement supplemented by law enforcement – lead to the next step, which is engineering.

“Some communities take it to the next level and start redesigning roads. They start to say, ‘This is a dangerous spot in the community. Maybe I could put traffic calming devices or make infrastructural changes,'” Randazzo said.

“The beauty of the enforcement data is not just that it, in and of itself, curbs behavior, because there’s a monetary component to it. But you can use that data for additional good to make the community safer through targeted engineering and education,” he said.

Discussing the program Friday, Allentown Mayor Matt Tuerk said he hoped the BusPatrol fines were being levied uniformly and questioned how it impacted an offender's socioeconomic status, and whether hefty fines were disproportionately impacting low-income individuals, among other concerns.

From a safe streets approach, he said the city’s plan remains focused on making smaller roadway safety improvements that won’t incur significant costs.

“This issue is as much a street design challenge as it is a safety challenge,” he said. “The purpose of this is for people to be safer on streets in the City of Allentown, but safety is very much a design question.”

He pointed to the Union Boulevard through Tilghman Street corridor — a 13.8-mile east to west roadway that extends into South Whitehall Township — as an area where funding will be applied hand-in-hand with data to make informed decisions on what should happen next.

‘The use of funds should go toward safety’

From the $300 fine generated by a BusPatrol citation, $250 goes to the school entity where the violation occurred, $25 to the primary police department, and $25 to the School Bus Safety Grant Program account.

Money paid to the school district is restricted — designated to be utilized for the installation, administration or maintenance of stop signal arm enforcement systems, including through a system administrator under an agreement with the district.

The sheer number of violations in Allentown has the potential to raise hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Tuerk said he would prefer some of that money go toward roadway safety. But he also advocated for another form of traffic enforcement: automated red light enforcement on city streets.

“Red light enforcement gets knocked because it’s a revenue-generating mechanism,” he said, but pledged he would send all revenue generated by such a program to be used for roadway safety improvements.

And there is evidence that both BusPatrol cameras and automated red light cameras make roads safer.

“It's been publicly reported that we see violation reductions, raw violation reductions anywhere, between 20 to 40% year over year, and we have a very, very low recidivism rate,” Randazzo said.

“We’ve been around since 2017 so aggregated across all of our programs nationwide, over 90% of folks who receive one violation in the mail stemming from a BusPatrol program, do not repeat offend.”

Similarly, a 2016 study of programs in 79 U.S. cities including Philadelphia by the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety — a nonprofit organization funded by insurance companies and industry backers — found automated red light cameras reduced the rate of all types of fatal crashes at intersections with signals by 14%.

Researchers argue they have “proven effective in changing drivers’ behaviors, reducing crashes and injuries and fatalities caused by crashes.”

Tuerk said he’s glad the conversation continues around safe driving, but it’s all part of a much bigger issue.

“It’s a long, long effort to get people to be more responsible operators of motor vehicles,” he said.

New legislation targets repeat offenders

Additional legislation also is being proposed to further enhance school bus safety laws in Pennsylvania.

State Sen. Nick Miller, a Democrat representing parts of Lehigh and Northampton counties, is co-sponsoring Senate Bill 65, which seeks to amend the state’s vehicle code.

2025-0-SB0065P0486 by LehighValley Newsdotcom on Scribd

The bill addresses criminal violations — those issued during a traffic stop by law enforcement, not from automated enforcement — and aims to deter repeat offenders.

Miller called the overall number of violations in the Lehigh Valley “astronomically high” and said that drivers passing stopped school buses is “just not acceptable.”

Key provisions of the bill include:

- Increasing the minimum stopping distance for oncoming traffic from 10 feet to 15 feet when a bus has its red or amber lights flashing and stop arm extended.

- Introducing harsher penalties for repeat offenders, including:

- A $500-plus fine

- Five points on a driver's license

- A 60-day license suspension

- A $35 surcharge to support the School Bus Safety Grant Program

- Mandatory attendance at a driver improvement school or completion of a special exam

The Senate Transportation Committee voted unanimously – by a vote of 14-0 – on March 26 to advance the legislation to the full Senate.

“This bill is moving in a bipartisan fashion. It's actually the second session that I'm supporting it,” Miller said.

The legislation was first introduced as SB 897 in 2023 and passed unanimously in the Senate in October of that year. But, the bill was not considered in the House in the 2023-2024 session, so it’s been reintroduced.

“This is just a common sense issue, and I think that distracted driving is one of the reasons,” Miller said. “People are on their phones and look up and there's those flashing lights, and then they blow by [a bus], and it's just not acceptable. Like I’ve said before, it puts parents and children at risk.”

Miller said the legislation addressing repeat offenders was critical.

“That's an area that I think that the stronger penalties are trying to get ahead of, the folks that are consistently violating this and being distracted drivers and putting our families at risk,” he said.

“It is an increase of penalty, popular or not. These numbers need to be going down, not up.”

‘The penalty should be higher’

“Even one incident of passing a school bus is one too many, PennDOT Secretary Mike Carroll said in a news conference last fall.

Carroll’s comments came after 2024’s Operation Safe Stop, in which participating school districts and law enforcement agencies witnessed 131 violations of the law.

Those numbers came from less than 5% of all districts on just one day from the 180-day school calendar.

As the school year has progressed, the violations have continued. But with each alleged violation, officers have to use their discretion to determine whether a violation actually occurred.

While BusPatrol's technology records stop arm violations, it's local police who actually authorize sending the citations to registered car owners.

“I will say there are violations that if you just hit ‘approve’ would be wrong,” said Salisbury's Losagio.

Despite the numbers approved this school year, he said Salisbury police are the opposite of a rubber stamp. They’ve approved “well under 50 percent” of the violations they've received from BusPatrol for review, he said.

“We always err on the side of discretion when reviewing these violations,” he said. “Did the motorist have enough time to safely stop? Was his or her view obstructed? Did the bus provide ample yellow light warning?

“We use the same standards as if we were sitting in a patrol car watching the violation,” Losagio said.

And those civil violations also should carry heftier penalties, he believes.

“If the state won’t pass legislation for a video violation to affect a driver’s license, I do believe the penalty (fine) should be higher,” he said, with funds dedicated to “more enforcement for this exact type of violation and education.”

“We all hear commercials for seat belt use and (messages) to not drink and drive, but when was the last time you saw anything about not passing a school bus?” Losagio asked.

“This would prevent any speculation that enforcement is being done as a ‘money maker’ because it truly is done out of safety.”

Allentown's Chief Roca didn't elaborate on his department's review process for the 3,000-plus violations recorded this year by BusPatrol technology.

On Friday, after days of questioning of various public officials by LehighValleyNews.com about the violations and the city's disproportionately large amount, Roca released a video on social media saying police were stepping up enforcement.

"When I take a look at it, I feel sick to my stomach," he says of the violations.

For her part, Clark said she’s happy people are getting "a nice fat bill in the mail.”

“I wish they would be required to watch their video in the payment portal. I wish they would make that mandatory to have to actually see their violation and it would carry a bigger penalty. Enforcement is such a big part of this,” she said.

“So until there’s more work in Harrisburg and suspension and points get addressed and added on to these civil violations … that’s what they should work on. That’s what our lawmakers should focus on.

“These people, especially the thousands in Allentown who are blowing past buses, what the messaging should be is this when they get that violation in the mail: Welcome to the consequences of your actions. How about you actually get punished.”